Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Japanese Morphological analysis

المؤلف:

David Odden

المصدر:

Introducing Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

176-6

5-4-2022

2026

Morphological analysis

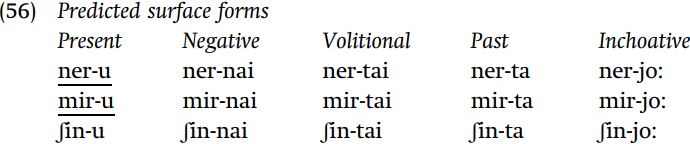

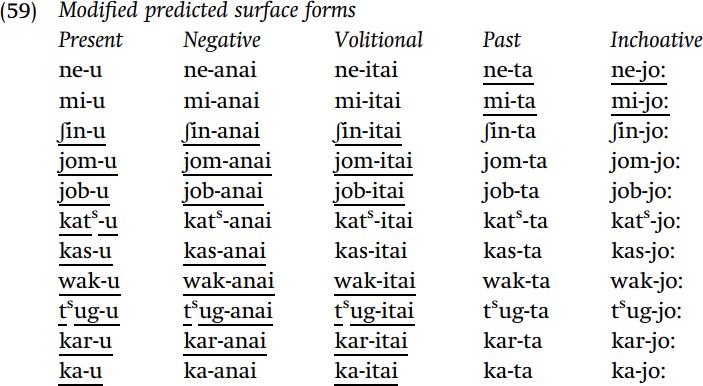

We could make an initial guess regarding suffixes, which leads to the following hypotheses: -u “present,” -nai “negative,” -tai “volitional,” -ta “past,” and -jo: “inchoative”: that analysis seems reasonable given the first two verbs in the data. We might also surmise that the root is whatever the present-tense form is without the present ending, i.e. underlying ner, mir, ʃin, jom, job, kats , kas, wak, t s ug, kar, and ka. In lieu of the application of a phonological rule, the surface form of a word should simply be whatever we hypothesize the underlying form of the root to be, plus the underlying form of added affixes. Therefore, given our preliminary theory of roots and suffixes in Japanese, we predict the following surface forms, with hyphens inserted between morphemes to make the division of words into roots and suffixes clear: it is important to understand the literal predictions of your analysis, and to compare them with the observed facts.

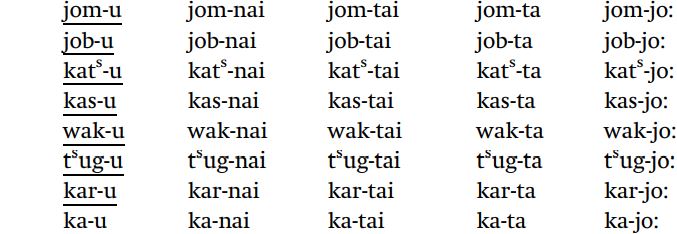

The forms which are correct as is are underlined: as we can see, all of the present-tense forms are correct, and none of the others is. It is no surprise that the present-tense forms would be correct, since we decided that the underlying form of the root is whatever we find in the present tense minus the vowel -u. It is possible, but unlikely, that every other word undergoes some phonological rule.

Changing our hypothesis. Since our first guess about underlying forms is highly suspect, we should consider alternative hypotheses. Quite often, the cause of analytic problems is incorrect underlying forms. One place to consider revising the assumptions about underlying representations would be those of the affixes. It was assumed – largely on the basis of the first two forms nenai and minai – that the negative suffix is underlyingly -nai. However, in most of the examples, this apparent suffix is preceded by the vowel a (ʃinanai, jomanai, jobanai, and so on), which suggests the alternative possibility that the negative suffix is really -anai. Similarly, the decision that the volitional suffix is underlyingly -tai was justified based on the fact that it appears as -tai in the first two examples; however, the suffix is otherwise always preceded by the vowel i (ʃinitai, jomitai, jobitai, and so on), so this vowel might analogously be part of the suffix.

One fact strongly suggests that the initial hypothesis about the underlying forms of suffixes was incorrect. The past-tense suffix, which we also assumed to be -ta, behaves very differently from the volitional suffix, and thus we have ʃinitai versus ʃinda, jomitai versus yonda, kat ʃ itai versus katta, karitai versus katta (there are similarities such as kaʃitai and kaʃita which must also be accounted for). It is quite unlikely that we can account for these very different phonological patterns by reasonable phonological rules if we assume that the volitional and past-tense suffixes differ solely by the presence of final i.

It is this realization, that there is a thorough divergence between the past-tense and volitional suffixes in terms of how they act phonologically, that provides the key to identifying the right underlying forms. Given how similar these two suffixes are in surface forms, -(i)tai vs. -(i)ta, but how differently they behave phonologically, they must have quite different underlying forms. Since the past-tense suffix rarely has a vowel and the volitional suffix usually does, we modify our hypothesis so that the volitional is /-itai/ and the past tense is /ta/. Because the negative acts very much like the volitional in terms of where it has a vowel, we also adopt the alternative that the negative is /anai/.

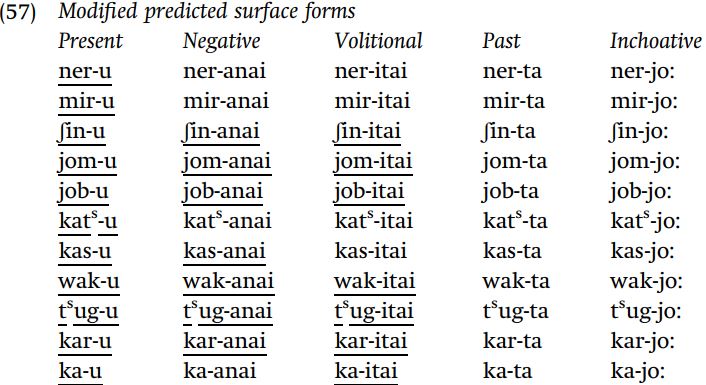

These changed assumptions about underlying representations of suffixes yield a significant improvement in the accuracy of our predicted surface forms, as indicated in (57), with correct surface forms underlined.

Implicitly, we know that forms such as predicted *[kats anai] (for [katanai]) and *[kas-itai] (for [kaʃitai]) must be explained, either with other changes in underlying forms, or by hypothesizing rules.

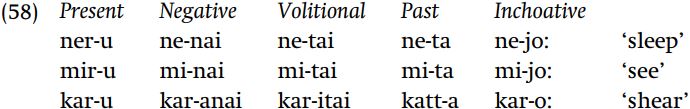

We will consider one further significant modification of the underlying representations, inspired by the success that resulted from changing our assumptions about -itai and -anai, in reducing the degree to which underlying and surface forms differ. The original and dubious decision to treat these suffixes as tai and nai was influenced by the fact that that is how they appear with the first two verbs. It is also possible that our initial hypothesis about the underlying form of these two verb roots was incorrect. There is good reason to believe that those assumptions were indeed also incorrect. Compare the surface form of the three verbs in our data set which, by hypothesis, have roots ending in r.

Clearly, the supposed roots /ner/ and /mir/ act quite differently from /kar/. The consonant r surfaces in most of the surface forms of the verb meaning ‘shear,’ whereas r only appears in verbs ‘sleep’ and ‘see’ in the present tense. In other words, there is little reason to believe that the first two roots are really /ner/ and /mir/, rather than /ne/ and /mi/: in contrast, there seems to be a much stronger basis for saying that the word for ‘shear’ is underlyingly /kar/. Now suppose we change our assumption about these two verbs, and assume that /ne/ and /mi/ end in vowels.

In terms of being able to predict the surface forms of verbs without phonological rules, this has resulted in a slight improvement of predictive power (sometimes involving a shuffling of correct and incorrect columns, where under the current hypothesis we no longer directly predict the form of the present tense, but we now can generate the past and inchoative forms without requiring any further rules). More important is the fact that we now have a principled basis, in terms of different types of underlying forms, for predicting the different behavior of the verbs which have the present tense neru, miru versus karu, which are in the first two cases actually vowel-final roots, in contrast to a consonant-final root.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)