Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Analyzing position classes

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P18-C2

2025-12-04

801

Analyzing position classes

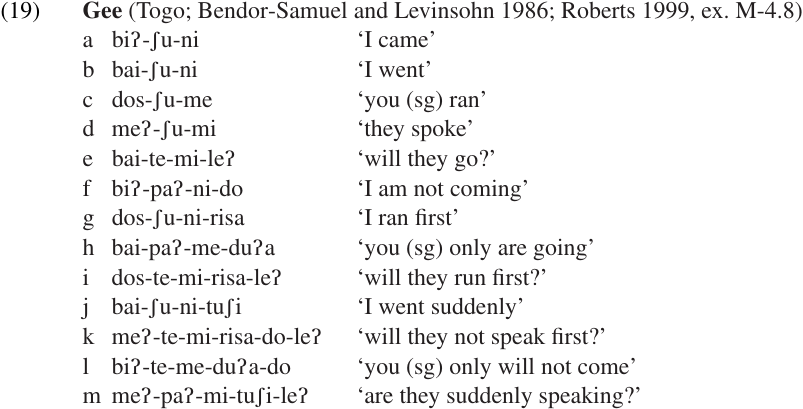

Let us work through the process involved in constructing a position class chart. The first step obviously is to identify each morpheme in the data, using the methods discussed in Identifying meaningful elements. We will practice with the following (slightly regularized) data from the Gee language of West Africa. For simplicity, morpheme boundaries are already marked:

Based on these data we can identify the following meanings for each morpheme:

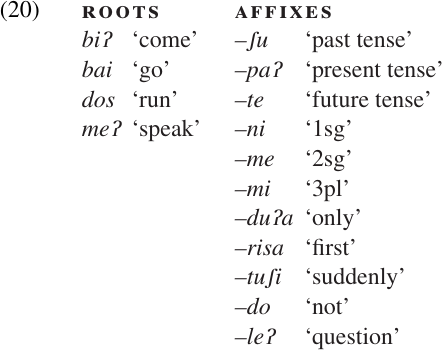

We begin the position class analysis by re-writing each word in the data onto a chart, with the longest words (i.e. those which contain the greatest number of morphemes) at the top. We line up all the roots in one column and arrange the affixes in such a way that: (i) no column in the chart contains more than one morpheme in any given word; and (ii) each individual morpheme always appears in the same column in all the words where it occurs.

One obvious way to do this is to start out with a separate column for each morpheme; in this example, that would mean 12 columns (1 for the root plus 1 for each of the 11 affixes). But it is much more helpful to make some initial guesses about which affixes might belong to the same position class. When several affixes have closely related meanings, or belong to the same grammatical category (tense, person, number, etc.), and no two of them are found in the same word, there is a good chance they will belong to the same class. In that case, we can write them in the same column in our initial chart.

The charting procedure itself will help us to find out if an initial hypothesis of this sort was mistaken. There are at least two ways in which this could happen. First, we might discover that two of the affixes which we have tentatively grouped together really can occur in the same word after all. Second, we might discover that two affixes have different ORDERING RELATIONSHIPS with respect to some other morpheme. For example, if we find in a certain language that the masculine and neuter gender markers occur as prefixes to the adjective root, while the feminine marker occurs as a suffix, we must split these elements into two separate position classes, even though they all express the same grammatical category (namely gender). This is necessary because the columns in a position class chart represent fixed linear ordering constraints. Every element in a given position class must have the same order as its fellows with respect to all elements of every other position class.

In our present example, we can see that the three tense markers (–ʃu,–paʔ, and–te) form a coherent group, as do the three subject-agreement markers (–ni,–me, and–mi); and there are no words which contain more than one element from either group. So our initial chart might look like (21).

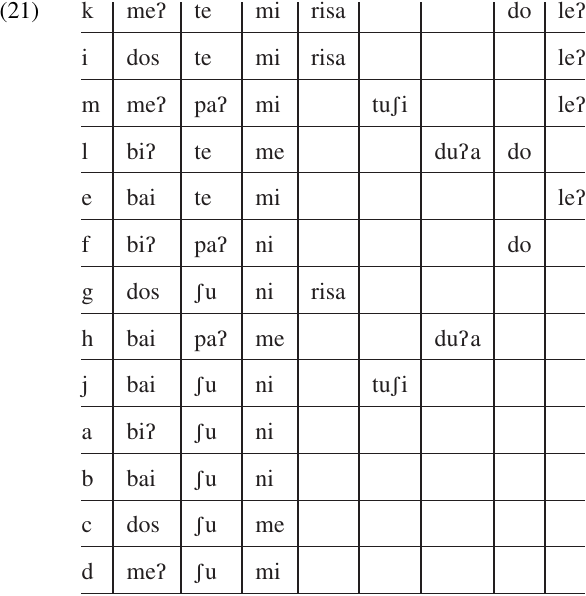

The next step is to inspect each column to see whether elements in that column ever co-occur with elements in the neighboring column to the left or right. If we find two adjacent columns that are never both filled in the same row, it would be possible to merge the two into a single column. The two sets of elements are said to be in COMPLEMENTARY DISTRIBUTION, meaning that no single word ever contains elements from both sets.

We would definitely want to merge the two columns if the meanings of the elements are related or form a coherent class in some way. On the other hand, if two adjacent columns appear to be in complementary distribution but there is no plausible relationship between the meanings of their elements, it may be better to leave the columns separate for the time being. Rather than merging the two, add a note at the bottom of your chart stating that these two sets of elements have not been found to co-occur. When you have a chance to collect more data, try to find examples where elements from both sets can occur together. If there are no (or very few) such words in the language, you have discovered a CO-OCCURRENCE RESTRICTION, which needs to be stated as part of the grammar of the language. Attempting to find explanations for these restrictions often leads to interesting discoveries, either about the current structure of the language or about its historical development.

In our present example, we can see that the three forms–risa, –tuʃi, and–duʔa never co-occur with each other, so it would be possible to collapse all three columns into one. The corresponding meanings (‘first,’ ‘suddenly,’ ‘only’) do not appear to be closely related, but neither are they in compatible; they all provide some information about the manner in which the action was performed. Unless further data reveal that two or more of them may co-occur, it seems reasonable to combine them into a single position class, as in (22).

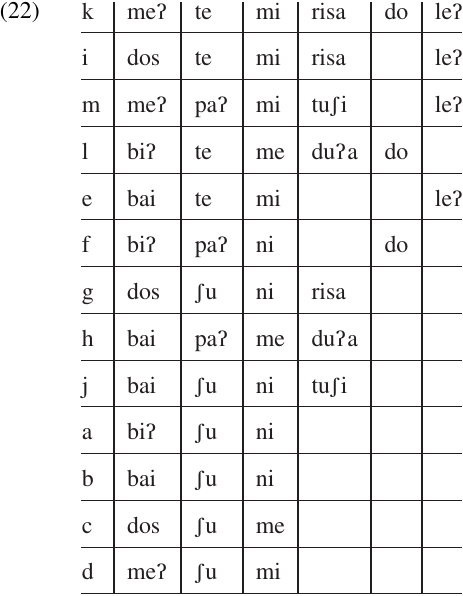

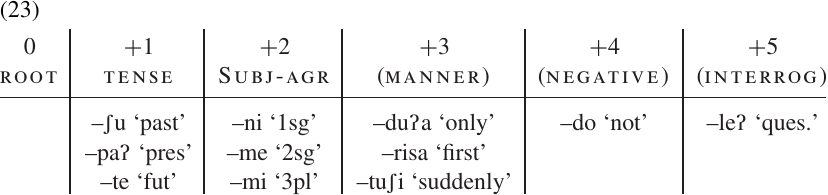

Since–do and–leʔ occur with each other and with elements of every other column in the chart, no further combination is possible. Tense and subject agreement appear to be obligatory, while the other classes are optional, so our final position class chart would look like this:

The identification of position classes is not a purely mechanical procedure. It involves judgments based on linguistic knowledge and intuition, which are developed with practice. Moreover, while position class charts are useful for a large number of languages, there are other languages for which they are less helpful.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)