Grammar

Grammar

Tenses

Tenses

Present

Present

Past

Past

Future

Future

Parts Of Speech

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Adverbs

Adjectives

Adjectives

Pronouns

Pronouns

Pre Position

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Preposition by function

Preposition by construction

Preposition by construction

Conjunctions

Conjunctions

Interjections

Interjections

Grammar Rules

Grammar Rules

Linguistics

Linguistics

Semantics

Semantics

Pragmatics

Pragmatics

Reading Comprehension

Reading Comprehension|

Read More

Date: 2024-05-17

Date: 2024-12-03

Date: 2024-12-11

|

Allophonic rules of pronunciation are found in most human languages, if not indeed all languages. What constitutes a subtle contextual variation in one language may constitute a wholesale radical difference in phonemes in another. The difference between unaspirated and aspirated voiceless stops in English is a completely predictable, allophonic one which speakers are not aware of, but in Hindi the contrast between aspirated and unaspirated voiceless consonants forms the basis of phonemic contrasts, e.g. [pal] ‘want’, [ph al] ‘fruit.’ Unlike the situation in English, aspiration in Hindi is an important, distinctive property of stops which cannot be supplied by a rule.

l and d in Tswana. The consonants [l] and [d] are clearly separate phonemes in English, given words such as lie and die or mill and mid. However, in Tswana (Botswana), there is no contrast between [l] and [d]. Phonetic [l] and [d] are contextually determined variants of a single phoneme: surface [l] appears before nonhigh vowels, and [d] appears before high vowels (neither consonant may come at the end of a word or before another consonant).

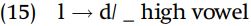

Tswana has a rule which can be stated as “/l/ becomes [d] before high vowels.”

An equally accurate and general statement of the distribution or [l] and [d] would be “/d/ becomes [l] before nonhigh vowels.”

There is no evidence to show whether the underlying segment is basically /l/ or /d/ in Tswana, so we would be equally justified in assuming either rule (15) or rule (16). Sometimes, a language does not provide enough evidence to allow us to decide which of two (or more) analyses is correct.

Tohono O’odham affricates. In the language Tohono O’odham (formerly known as Papago: Arizona and Mexico), there is no contrast between [d] and [dʒ ], or between [t] and [tʃ ]. The task is to inspect the examples in (17) and discover what factor governs the choice between plain alveolar [d, t] versus the alveopalatal affricates [dʒ , tʃ ]. In these examples, word-final sonorants are devoiced by a regular rule which we disregard, explaining the devoiced m in examples like [wahtʃ um̥ ]

We do not know, at the outset, what factor conditions the choice of [t, d] versus [tʃ , dʒ ] (indeed, in the world of actual analysis we do not know in advance that there is any such relationship; but to make your task easier, we will at least start with the knowledge that there is a predictable relationship, and concentrate on discovering the rule governing that choice). To begin solving the problem, we explore two possibilities: the triggering context may be the segment which immediately precedes the consonant, or it may be the segment which immediately follows it.

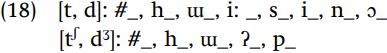

Let us start with the hypothesis that it is the immediately preceding segment which determines how the consonant is pronounced. In order to organize the data so as to reveal what rule might be at work, we can simply list the preceding environments where stops versus affricates appear, so h_ means “when [h] precedes” – here, the symbol “#” represents the beginning or end of a word. Looking at the examples in (17), and taking note of what comes immediately before any [t, d] versus [tʃ , dʒ ], we arrive at the following list of contexts:

Since both types of consonants appear at the beginning of the word, or when preceded by [h] or [ɯ], it is obvious that the preceding context cannot be the crucial determining factor. We therefore reject the idea that the preceding element determines how the phoneme is pronounced.

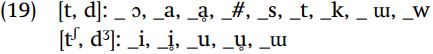

Focusing next on what follows the consonant, the list of contexts correlated with plain stops versus affricates is much simpler.

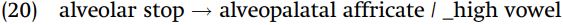

Only the vowels [i, u, ɯ] (and their devoiced counterparts) follow [tʃ ] and [dʒ ], and the vowels [a, ɔ] follow [t] and [d]. Moreover, when no vowel follows, i.e. at the end of the word or before another consonant, the plain alveolar appears (taht, tɔdsid). The vowels [i, u, ɯ] have in common the property that they are high vowels, which allows us to state the context for this rule very simply: /t/ and /d/ become alveopalatal affricates before high vowels, i.e.

The retroflex consonant [ɖ] does not undergo this process, as seen in [mɯɖɯdam̥ ].

This account of the distribution of alveolars versus alveopalatals assumes that underlyingly the consonants are alveolars, and that just in case a high vowel follows, the consonant becomes an alveopalatal affricate. It is important to also consider the competing hypothesis that underlyingly the consonants are alveopalatals and that they become alveolars in a context which is complementary to that stated in rule (20). The problem with that hypothesis is that there is no natural statement of that complementary context, which includes nonhigh vowels, consonants, and the end of the word.

The brace notation is a device used to force a disjunction of unrelated contexts into a single rule, so this rule states that alveopalatal affricates become alveolar stops when they are followed either by a nonhigh vowel, a consonant, or are at the end of the word, i.e. there is no coherent generalization. Since the alternative hypothesis that the consonants in question are underlyingly alveopalatals leads to a much more complicated and less enlightening statement of the distribution of the consonants, we reject the alternative hypothesis and assume that the consonants are underlyingly alveolar

Obstruent voicing in Kipsigis. In the Kipsigis language of Kenya, there is no phonemic contrast between voiced and voiceless obstruents as there is in English. No words are distinguished by the selection of voiced versus voiceless consonants: nevertheless, phonetic voiced obstruents do exist in the language.

In these examples, we can see that the labial and velar consonants become voiced when they are both preceded and followed by vowels, liquids, nasals, and glides: these are all sounds which are voiced.

In stating the context, we do not need to say “voiced vowel, liquid, nasal, or glide,” since, by saying “voiced” alone, we refer to the entire class of voiced segments. It is only when we need to specifically restrict the rule so that it applies just between voiced consonants, for example, that we would need to further specify the conditioning class of segments.

While you have been told that there is no contrast between [k] and [g] or between [p] and [b] in this language, children learning the language do not use explicit instructions, so an important question arises: how can you arrive at the conclusion that the choice [k, p] versus [g, b] is predictable? Two facts lead to this conclusion. First, analyzing the distribution of consonants in the language would lead to discovering the regularities that no word begins or ends in [b, g] and no word has [b, g] in combination with another consonant, except in combination with the voiced sonorants. We would also discover that [p, k] do not appear between vowels, or more generally between voiced segments. If there were no rule governing the distribution of consonants in this language, then the distribution is presumed to be random, which would mean that we should find examples of [b, g] at the beginning or end of words, or [p, k] between vowels.

Another very important clue in understanding the system is the fact that the pronunciation of morphemes will actually change according to the context that they appear in. Notice, for example, that the imperative form [kuur] ‘call!’ has a voiceless stop, but the same root is pronounced as [guur] in the infinitive [ke-guur] ‘to call.’ When learning words in the language, the child must resolve the changes in pronunciation of word parts in order to know exactly what must be learned. Sometimes the root ‘call’ is [kuur], sometimes [guur] – when are you supposed to use the pronunciation [guur]? Similarly, in trying to figure out the root for the word ‘dog,’ a child will observe that in the singular the root portion of the word is pronounced [ŋok], and in the plural it is pronounced [ŋog]. From observing that there is an alternation between [k] and [g], or [p] and [b], it is a relatively simple matter to arrive at the hypothesis that there is a systematic relation between these sounds, which leads to an investigation of when [k, p] appear, versus [g, b].

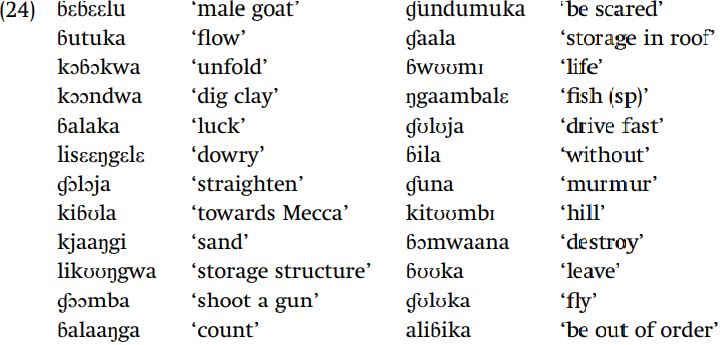

Implosive and plain voiced stops in Matuumbi. The distinction between implosive and plain voiced consonants in Matuumbi (Tanzania) can be predicted by a rule.

Upon consideration of consonant distribution in these data, you will see that implosives appear in word-initial position and after vowels, whereas plain voiced consonants appear exclusively after nasals.

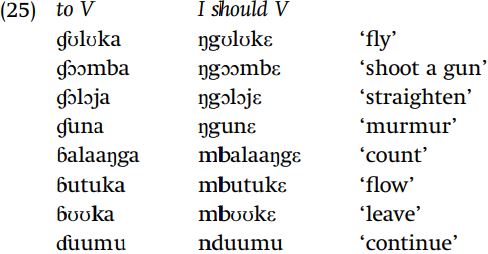

There is further clinching evidence that this generalization is valid. In this language, the first-person-singular form of the verb has a nasal consonant prefix (there is also a change in the final vowel, where you get -a in the infinitive and -ε in the “should” form, the second column below).

Thus the pronunciation of the root for the word for ‘fly’ alternates between [ɠʊlʊk] and [gʊlʊk], depending on whether a nasal precedes.

Having determined that implosives and plain voiced stops are allophonically related in the grammar of Matuumbi, it remains to decide whether the language has basically only plain voiced consonants, with implosives appearing in a special environment; or should we assume that Matuumbi voiced stops are basically implosive, and plain voiced consonants appear only in a complementary environment? The matter boils down to the following question: is it easier to state the context where imposives appear, or is it easier to state the context where plain voiced consonants appear? We generally assume that the variant with the most easily stated distributional context is the variant derived by applying a rule. However, as we saw with the case of [l] and [d] in Tswana, a language may not provide empirical evidence which is the correct solution.

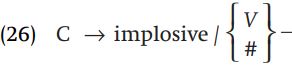

Now let us compare the two possible rules for Matuumbi: “implosives appear word initially and after a vowel”:

versus “plain consonants appear after a nasal”:

It is simpler to state the context where plain consonants appear, since their distribution requires a single context – after a nasal – whereas describing the process as replacement of plain consonants by implosives would require a more complex disjunction “either after a vowel, or in word-initial position.” A concise description of contexts results if we assume that voiced consonants in Matuumbi are basically implosive, and that the nonimplosive variants which appear after nasals are derived by a simple rule: implosives become plain voiced consonants after nasals.

It is worth noting that another statement of the implosive-to-plain process is possible, since sequences of consonants are quite restricted in Matuumbi. Only a nasal may precede another “true” consonant, i.e. a consonant other than a glide. A different statement of the rule is that plain voiced consonants appear only after other consonants – due to the rules of consonant combination in the language, the first of two true consonants is necessarily a nasal, so it is unnecessary to explicitly state that the preceding consonant in the implosive-to-plain-C rule is a nasal. Phonological theory does not always give a single solution for any given data set, so we must accept that there are at least two ways of describing this pattern. One of the goals of the theory, towards which considerable research energy is being expended, is developing a principled basis for making a unique and correct choice in such cases where the data themselves cannot show which solution is right.

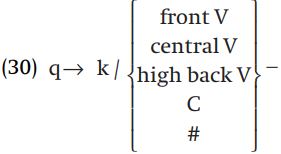

Velar and uvular stops in Kenyang. In Kenyang (Cameroon), there is no contrast between the velar consonant k and uvular q.

What determines the selection of k versus q is the nature of the vowel which precedes the consonant. The uvular consonant q is always preceded by one of the back nonhigh vowels o, ɔ, or ɑ, whereas velar k appears anywhere else.

This relation between vowels and consonants is phonetically natural. The vowels triggering the change have a common place of articulation: they are produced at the lower back region of the pharynx, where q (as opposed to k) is articulated.

An alternative is that the underlying segment is a uvular, and velar consonants are derived by rule. But under that assumption, the rule which derives velars is very complex. Velars would be preceded by front or central vowels, by high back vowels, by a consonant (ŋ), or by a word boundary. We would then end up with a disjunction of contexts in our statement of the rule.

The considerably more complex rule deriving velars from uvulars leads us to reject the hypothesis that these segments are underlyingly uvular. Again, we are faced with one way of capturing the generalization exploiting phonetically defined classes, and an alternative that involves a disjunctive list, where there is nothing that unifies the contexts: we select the alternative which allows a rule to be stated that refers to a simple, phonetically definable context. This decision reflects an important discovery regarding the nature of phonogical rules which will be discussed in greater detail in chapter 3, namely that phonological rules operate in terms of phonetic classes of segments.

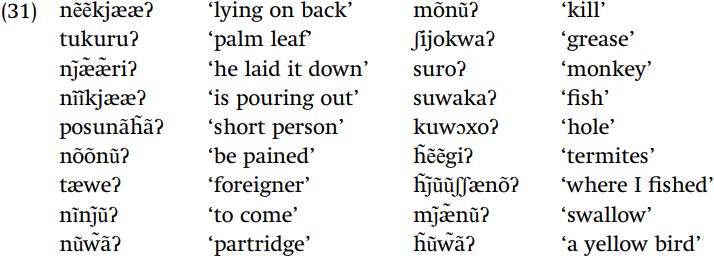

Arabela nasalization. Nasalization of vowels and glides is predictable in Arabela (Peru).

Scanning the data in (31), we see nothing about the following phonetic context that explains occurrence of nasalization: both oral and nasal vowels precede glottal stop ([tæweʔ] ‘foreigner’ versus [nõõnũʔ] ‘be pained’), [k] ([nĩĩkjææʔ] ‘is pouring out’ versus [ʃijokwaʔ] ‘grease’) or [n] ([mȷæ̃ ̃nũʔ] ‘swallow’ versus [posunãh̃ãʔ] ‘short person’). A regularity does emerge once we look at what precedes oral versus nasal vowels: when a vowel or glide is preceded by a nasal segment – be it a nasal consonant (including [h̃] which is always nasal in this language), vowel, or glide – then a vowel or glide becomes nasalized. The rule for nasalization can be stated as “a vowel or glide becomes nasalized after any nasal sound.”

The naturalness of this rule should be obvious – the essential property that defines the conditioning class of segment, nasality, is the very property that is added to the vowel: such a process, where a segment becomes more like some neighboring segment, is known as an assimilation. Predictable nasalization of vowels almost always derives from a nasal consonant somewhere near the vowel.

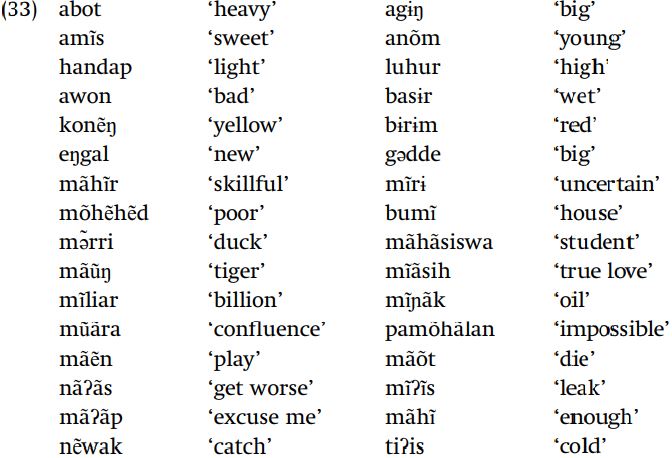

Sundanese: a problem for the student to solve. Bearing this suggestion in mind, where do nasalized vowels appear in Sundanese (Indonesia), given these data?

Since the focus at the moment is on finding phonological regularities, and not on manipulating a particular formalism (which we have not yet presented completely), you should concentrate on expressing the generalization in clear English.

We can also predict the occurrence of long (double) consonants in Sundanese, using the above data supplemented with the data in (34).

What rule determines the length of consonants in this language?

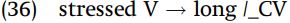

Vowel length in Mohawk. The context for predicting some variant of a phoneme may include more than one factor. There is no contrast between long and short vowels in Mohawk (North America): what is the generalization regarding where long versus short vowels appear?

One property which holds true of all long vowels is that they appear in stressed syllables: there are no unstressed long vowels. However, it would be incorrect to state the rule as lengthening all stressed vowels, because there are stressed short vowels as in [ˈwisk]. We must find a further property which distinguishes those stressed vowels which become lengthened from those which do not. Looking only at stressed vowels, we can see that short vowels appear before two consonants and long vowels appear before a consonant-plus-vowel sequence. It is the combination of two factors, being stressed and being before the sequence CV, which conditions the appearance of long vowels: stressed vowels are lengthened if they precede CV, and vowels remain short otherwise. We hypothesize the following rule:

Since there is no lexical contrast between long and short vowels in Mohawk, we assume that all vowels have the same underlying length: all long and shortened in one context, or all short and lengthened in the complementary context. One hypothesis about underlying forms in a given language results in simpler grammars which capture generalizations about the language more directly than do other hypotheses about underlying forms. If all vowels in Mohawk are underlyingly long, you must devise a rule to derive short vowels. No single generalization covers all contexts where supposed vowel shortening takes place, so your analysis would require two rules, one to shorten unstressed vowels, and another to shorten vowels followed by two consonants. In comparison, the single rule that stressed vowels lengthen before CV accounts for vowel length under the hypothesis that vowels in Mohawk are underlyingly short. No other rule is needed: short vowels appear everywhere that they are not lengthened.

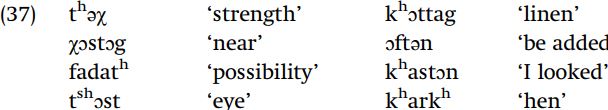

Aspiration in Ossetic. Aspiration of voiceless stops can be predicted in Ossetic (Caucasus).

Since aspirated and plain consonants appear at the end of the word ([t shɔst] ‘eye,’ [t shət h ] ‘honor’), the following context alone cannot govern aspiration. Focusing on what precedes the consonant, aspirates appear word-initially, or when preceded by a vowel or [r] (i.e. a sonorant) at the end of the word; unaspirated consonants appear when before or after an obstruent. It is possible to start with unaspirated consonants (as we did for English) and predict aspiration, but a simpler description emerges if we start from the assumption that voiceless stops are basically aspirated in Ossetic, and deaspirate a consonant next to an obstruent. The relative simplicity of the resulting analysis should guide your decisions about underlying forms, and not a priori decisions about the phonetic nature of the underlying segments that your analysis results in.

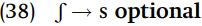

Optional rules. Some rules of pronunciation are optional, often known as “free variation.” In Makonde (Mozambique), the phoneme /ʃ/ can be pronounced as either [s] or [ʃ] by speakers of the language: the same speaker may use [s] one time and [ʃ] another time. The verb ‘read’ is thus pronounced as ʃoomja or as soomja, and ‘sell’ is pronounced as ʃuluuʃa or as suluusa. We will indicate such variation in pronunciation by giving the examples as “ʃuluuʃa ~ suluusa,” meaning that the word is pronounceable either as ʃuluuʃa or as suluusa, as the speaker chooses. Such apparently unconditioned fluctuations in pronunciation are the result of a rule in Makonde which turns /ʃ/ into [s]: this rule is optional. The optional nature of the rule is indicated simply by writing “optional” to the side of the rule

Normally, any rule in the grammar always applies if its phonological conditions are satisfied. An optional rule may either apply or not, so for any optional rule at least two phonetic outcomes are possible: either the rule applies, or it does not apply. Assuming the underlying form /ʃoomja/, the pronunciation [ʃoomja] results if the rule is not applied, and [soomja] results if the rule is applied.

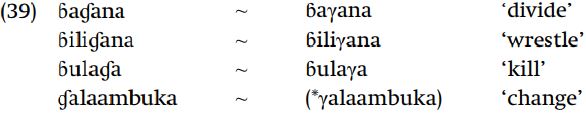

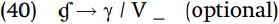

Optional rules may have environmental conditions on them. In Matuumbi, as we have seen in (24), voiced stops are implosive except after a nasal. The voiced velar stop exhibits a further complication, that after a vowel (but not initially) underlying /ɠ/ optionally becomes a fricative [γ] (the symbol “~” indicates “may also be pronounced as”).

Hence the optional realization of /ɠ/ as [γ], but only after a vowel, can be explained by the following rule.

The factors determining which variant is selected are individual and sociological, reflecting age, ethnicity, gender, and geography, inter alia. Phonology does not try to explain why people make the choices they do: that lies in the domain of sociolinguistics. We are also only concerned with systematic options. Some speakers of English vary between [æks] and [æsk] as their pronunciation of ask. This is a quirk of a particular word: no speaker says *[mæks] for mask, or *[fɪsk] for fix.

It would also be mistaken to think that there is one grammar for all speakers of English (or German, or Kimatuumbi) and that dialect variation is expressed via a number of optional rules. From the perspective of grammars as objects describing the linguistic competence of individuals, an optional rule is countenanced only if the speaker can actually pronounce words in multiple ways. In the case of Makonde, some speakers actually pronounce /ʃoomja/ in two different ways.

|

|

|

|

للعاملين في الليل.. حيلة صحية تجنبكم خطر هذا النوع من العمل

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"ناسا" تحتفي برائد الفضاء السوفياتي يوري غاغارين

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

نحو شراكة وطنية متكاملة.. الأمين العام للعتبة الحسينية يبحث مع وكيل وزارة الخارجية آفاق التعاون المؤسسي

|

|

|