Count nouns and mass nouns

المؤلف:

Patrick Griffiths

المؤلف:

Patrick Griffiths

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Semantics And Pragmatics

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Semantics And Pragmatics

الجزء والصفحة:

55-3

الجزء والصفحة:

55-3

12-2-2022

12-2-2022

1893

1893

Count nouns and mass nouns

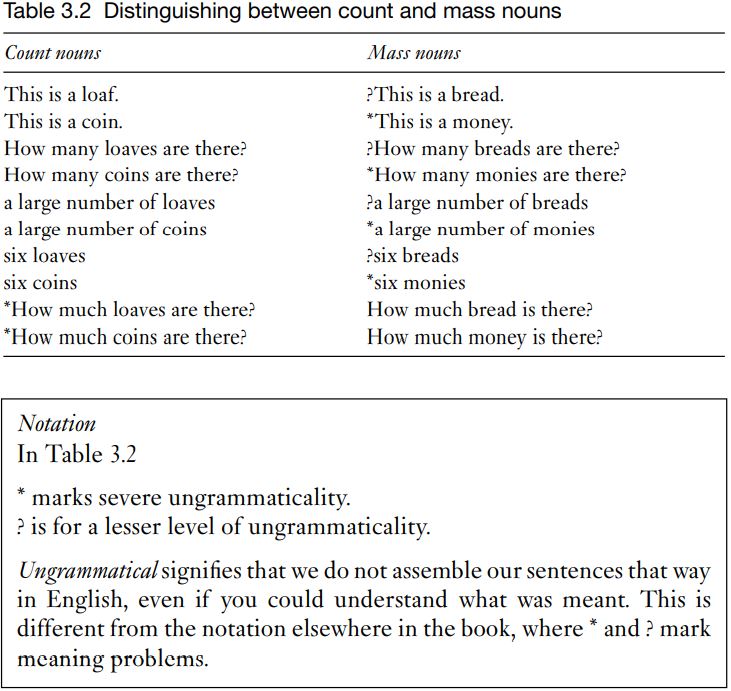

In the grammar of English, there is a clear distinction between count nouns, exemplified by loaf and coin in Table 3.2, and mass nouns, exemplified by bread and money. The whole noun vocabulary divides into words that are almost always count nouns (garment for instance), ones that are almost always mass nouns (like clothing) and ambiguous ones which can be used as either mass or count nouns (like cake).

The question marks in Table 3.2 are there because of a special use allowable with some mass nouns, as when bread is taken to denote ‘distinct variety of bread’. For example, one might say of a bakery that it produces “six breads” to mean that it produces ‘six types of bread’: wholewheat, focaccio, French sticks, and so on. Six breads is ungrammatical for attempting to express the meaning ‘six loaves’.

Mass nouns resist being quantified with numbers and plural suffixes or the word many or the singular indefinite article a (right-hand column in Table 3.2), while count nouns (in the left-hand column) can be quantified in this way. Count nouns denote distinguishable whole entities, like beans or people or shirts. They can be counted. Mass nouns are quantified with the word much. They denote undifferentiated substance, like dough or water or lava.

Table 3.2 shows that the difference between count nouns and mass nouns is partly a matter of how the speaker or writer chooses to portray reality. What is out there in the world is pretty much the same whether you are referring to a loaf or to bread; likewise, the denotation of the words coins (and banknotes or bills) is pretty much the same as that of the word money. However, count nouns portray what we are talking about as consisting of individually distinct wholes (loaves, coins, banknotes, bills and so on), while talking about almost the same reality with mass nouns represents it as homogeneous substance, undifferentiated “stuff ”. Another pair that could have been selected to illustrate this is drinks (count) and booze (mass).

It is certainly not the case that when people use mass nouns to talk or write about clothing or bread or money or scenery, that they become incapable of distinguishing shirts from socks, or one sock from another, or seeing boundaries between the lakes, mountains and seascapes that go to make up scenery. They are merely treating scenery or money or what-ever as if “how much” were the only difference there could be between one “dollop” of the stuff and any other dollop of it.

Hyponymy and incompatibility have been illustrated almost entirely with count nouns. However, these two relations exist among mass nouns too. Velvet ‘cloth with a silky nap’, corduroy ‘cloth with a corrugated nap’, gingham and so on are mass nouns that are incompatible hyponyms of the mass noun cloth. (The mass noun cloth is the one seen in How much cloth is produced annually? There is a count noun cloth too, for instance in You’ll never use all these old cloths for wiping oil off your bicycle; throw some of them away.)

Only individuated wholes are represented in English as having parts. Homogenous substance is not separable into distinct parts. Therefore, only count nouns bear has-relations to labels for their parts; mass nouns do not enter the has-relation (except in physical chemistry, but that is another story).

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة