Predictable allomorphy

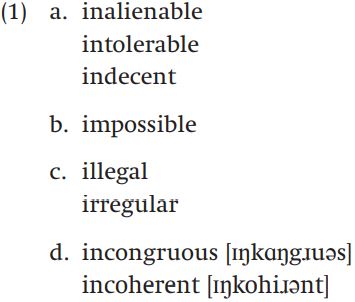

Let’s look more closely at the prefix in- in English. As the examples in (1a) show, it frequently has the form in-. However, sometimes it appears as im-, il-, or ir-, as the examples in (b) and (c) show. And if you think about sound rather than spelling, it can also be pronounced [ɪŋ-], as the examples in (1d) show:

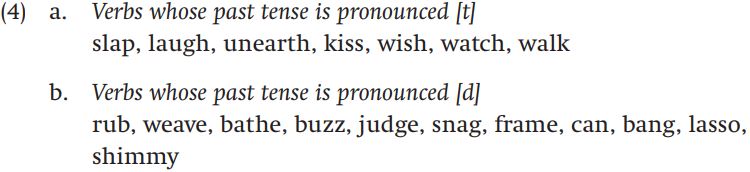

The various allomorphs of the negative prefix in- in English are quite regular, in the sense that we can predict exactly where each variant will occur. Which allomorph occurs depends on the initial sound of the base word. For vowel-initial words, like alienable, the [ɪn-] variant appears. It appears as well on words that begin with the alveolar consonants [t, d, s, z, n]. On words that begin with a labial consonant like [p], we find [ɪm-]. Words that begin with [l] or [r] are prefixed with the [ɪl-] or [ɪr-] allomorphs respectively, and words that begin with a velar consonant [k], are prefixed with the [ɪŋ-] variant. What you should notice is that this makes perfect sense phonetically: the nasal consonant of the prefix matches at least the point of articulation of the consonant beginning its base, and if that consonant is a liquid [l,r] it matches that consonant exactly. This allomorphy is the result of a process called assimilation. Generally speaking, assimilation occurs when sounds come to be more like each other in terms of some aspect of their pronunciation.

If you have studied a bit of phonology, you know that regularities in the phonology of a language can be stated in terms of phonological rules. Phonologists assume that native speakers of a language have a single basic mental representation for each morpheme. Regular allomorphs are derived from the underlying representation using phonological rules. For example, since the English negative prefix in- is pronounded [ɪn] both before alveolar-initial bases (tolerable, decent) and before vowel-initial bases (alienable), whereas the other allomoprhs are only pronounced before specific consonant-initial bases, phonologists assume that our mental representation of in- is [ɪn] rather than [ɪr], [ɪl], or [ɪŋ]; often (but not always, as we will see below) the underlying form of a morpheme is the form that has the widest surface distribution.2 When the underlying form is prefixed to a base beginning with anything other than a vowel or alveolar consonant, the following phonological rule derives the correct allomorph:

Phonologists use different forms of notation to express the above rule in a more succinct fashion, but we’ll restrict ourselves to informal statements of rules here.

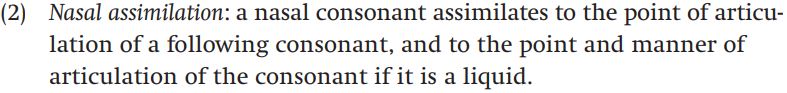

This sort of assimilation – called nasal assimilation – is not unusual in the languages of the world. We find something similar in the language Zoque (Nida 1946/1976: 21):

As the examples in (3) show, the possessive prefix is a nasal consonant that has three different allomorphs. Which allomorph is prefixed depends on the point of articulation of the noun it attaches to. In Zoque, we might say that part of forming the possessive of a noun involves prefixing an underlying nasal consonant which undergoes a phonological rule that assimilates it to a following consonant.

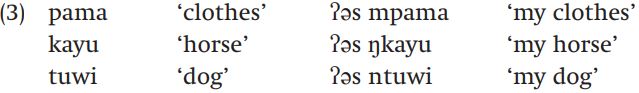

Another example of a predictable form of allomorphy is the formation of the regular past tense in English .We looked at the past tense in English in the context of figuring out what the mental lexicon looks like. We can now go into its formation in somewhat more detail. Consider the data in (4), which shows two of the three allomorphs of the regular past tense:

The regular past tense in English illustrates a different sort of assimilation, called voicing assimilation where sounds become voiced or voiceless depending on the voicing of neighboring sounds. The verbs that take the past tense allomorph [t] all end in voiceless consonants: [p, f, θ, s, ʃ, ʧ, k]. Those that take the [d] allomorph, all end either in a voiced consonant [b, v, ð, z, ʤ, g, m, n, ŋ] or in a vowel (and all vowels are voiced, of course). Why just this distribution? Clearly, the past tense morpheme has come to match the voicing of the final segment of the verb base: verbs whose last segment is voiceless take the voiceless variant.

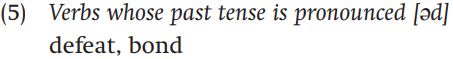

There is one allomorph of the past tense we haven’t covered yet. Consider what happens if the verb base ends in either [t] or [d]:

Here, a process of dissimilation is at work. Dissimilation is a phonological process which makes sounds less like each other. A schwa separates the [t] or [d] of the past tense from the matching consonant at the end of the verb. Again, this makes perfect sense phonetically; if the [t] or [d] allomorph were used, it would be indistinguishable from the final consonant of the verb root.

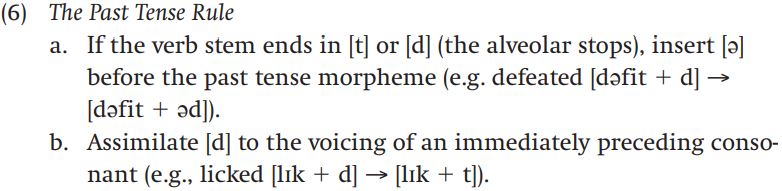

What is the underlying form of the past tense morpheme in English? As I indicated before, it is often a good strategy to assume that the allomorph with the widest distribution is the underlying form. But there is something else to consider as well. Phonologists typically assume that the underlying form of a morpheme must be something from which all of the other allomorphs can be derived using the simplest possible set of rules. In this case, the allomorph [d] has the widest distribution, because it occurs with all voiced consonants except [d], and with all vowel-final verb stems. And if we assume that the underlying form of the regular past tense is [d], we need only two simple rules to derive the other allomorphs:

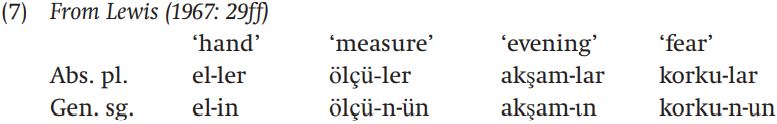

A third example of regular and predictable allomorphy comes from Turkish. As we’ve seen, in Turkish, virtually every morpheme, derivational and inflectional alike, has more than one allomorph. For example, the plural morpheme has the allomorphs -ler and -lar, and the genitive suffix has the allomorphs -in, -un, -ɩn, and -ün. The reason for this is that Turkish displays a process of vowel harmony whereby all non-high vowels in a word have to agree in backness, and all high vowels in both backness and roundness. When suffixes are added to a base, they must agree in the relevant vowel characteristics with the preceding vowels of the base:

Since the roots of the nouns el ‘hand’ and ölçü ‘measure’ have front vowels, the plural suffix must agree with them in frontness, so the -ler allomorph appears. On the other hand, akşam ‘evening’ and korku ‘fear’ have back vowels, and the -lar allomorph appears. Since the genitive ending has a high vowel, the vowel harmony is more complicated. If the noun root consists of vowels that are front and non-round, we find the genitive allomorph with a front, non-round vowel, that is, -in. Similarly, if the root contains front, round vowels, so does the suffix; so ölçü gets the front round allomorph -ün. Roots with back non-round vowels like akşam take the -ɩn allomorph, and roots with back round vowels like korku take the -un allomorph.

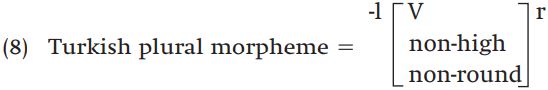

We might ask in this case what the underlying form of these affixes is, and here it’s a bit difficult to pick one of the existing allomorphs as our choice. For example, neither plural allomorph -ler nor -lar has a wider distribution than the other. One possibility that we might consider, then, is that the mental representation of the plural morpheme in Turkish is something like what we find in (8):

Part of the rule of vowel harmony in Turkish might then say that a nonhigh vowel in a suffix comes to match the backness of the vowels in a root that precedes it.

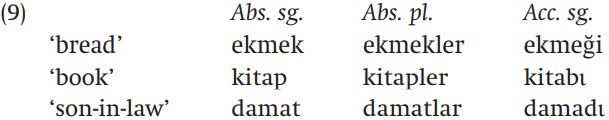

Our final example of predictable allomorphy also comes from Turkish, but this time it concerns consonants, rather than vowels. Let’s look at a bit more data from Turkish, in Lewis (1967: 10):

You already know that the plural morpheme in Turkish is -ler/-lar (or in its underlying form in (8)). This of course suggests that the roots of the nouns ‘bread’, ‘book’, and ‘son-in-law’ are ekmek, kitap, and damat respectively. When we look at the third column of examples, it appears that the accusative singular ending is -i/-ɩ but we find that the roots now end in ğ, b, and d. In other words, where the roots normally end in voiceless consonants, in the accusative singular they appear to have allomorphs that end in voiced consonants.3 In the absolute case, the voiceless consonants are at the end of the word, and in the absolute plural they occur before another consonant, but in the accusative singular forms, the root-final consonant is now between vowels. What occurs is a process that is called intervocalic voicing. In other words, a consonant is voiced when it occurs between two vowels .

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة