Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Nishnaabemwin (Algonquian)

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

129-7

24-1-2022

1484

Nishnaabemwin (Algonquian)

The final language we will look at is Nishnaabemwin, an Algonquian language spoken in southern Ontario, Canada (Valentine 2001). It makes heavy use of affixation, especially suffixation, and has an extremely rich system of inflection. What’s most interesting about Nishnaabemwin, however, is the way that it combines bound morphemes to form new lexemes.

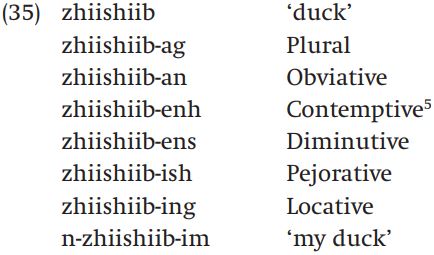

Let’s look first at inflection. Nouns have either animate or inanimate gender. They can be inflected for number, and have different forms for diminutive, pejorative, and what is called ‘contemptive’, a suffix that adds a negative meaning, but one that is less strongly negative than the pejorative suffix. Nouns can also occur in a locative form, and what is called the ‘obviative’ form, which serves to distance a noun from the speaker in a narrative. Finally, there are prefixes and suffixes that indicate possession of a noun. Some of the relevant forms for the noun zhiishiib ‘duck’ are given in (35):

These inflections are not mutually exclusive. If they occur in combination, the diminutive, for example, must precede the pejorative, which in turn precedes the suffix that occurs in the possessive. Nor are these the only inflections that can appear on nouns: this is just a small selection!

Verb inflection is even more complex than noun inflection, and we cannot really do justice to it here. But just to give you a taste of how verintricate the inflection of verbs is in Nishnaabemwin, consider Valentine’s (2001: 219) description of the inflectional possibilities of intransitive verbs that take animate subjects:

The independent form of the verb is used in main clauses, and differently inflected forms are used in subordinate clauses (the conjunct form) and in imperatives. By polarities, Valentine means that verbs have different forms for positive and negative. Compare this to the four forms of the verb walk in English (walk, walks, walked, walking); English uses the same forms of the verb in main and subordinate clauses, and uses a separate word for negation.

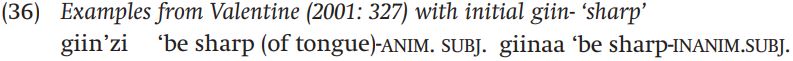

Derivation is no less complex than inflection in this language: words rarely consist of a single root morpheme. Instead, various bound morphemes are joined together to form words. Intransitive verbs, for example, frequently consist of two or three pieces. The last piece, called the ‘final’, expresses a verbal concept. The first piece, called the ‘initial’, expresses something that modifies the verbal concept; in English we would express similar concepts with separate adjectives, adverbs, or prepositions:

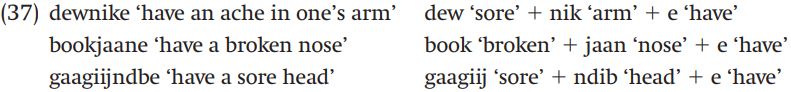

Verbs may also have a third piece that occurs between the initial and the final; this is called the ‘medial’ and corresponds to what in English would usually be a nominal concept (Valentine 2001: 330, 334):

Such forms can undergo further derivation by adding another final element, so from gaagiijndbe ‘have a sore head’ we can get gaagiijndbekaazo, which means ‘pretend to have a sore head’ by adding the final -kaazo, which means ‘pretend to’. And of course each of these verbs can then take various inflectional elements.

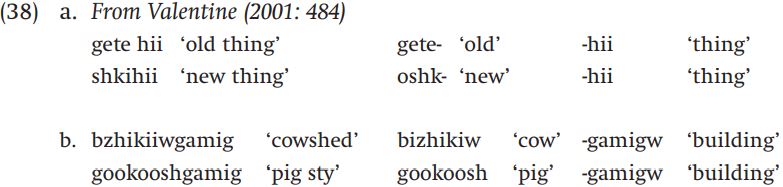

Nouns can be made up of several bound morphemes as well. For example, the nouns in (38a) are made up of an initial bound element that has an adjectival sort of meaning, and a second bound element that means ‘thing’. Those in (38b) have an initial element that is a free form, and a bound final element that means ‘building, habitation':

Valentine uses terms like ‘initial’, ‘medial’, and ‘final’, rather than calling the bound morphemes that make up these forms ‘prefixes’ or ‘suffixes’, probably because these morphemes are much more like roots than like affixes in their meanings. We might therefore think of them as bound bases.

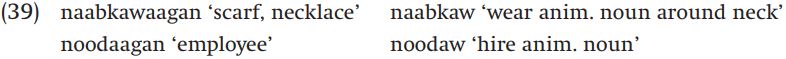

There are some derivational suffixes in Nishnaabemwin, however. For example the suffix -aagan creates nouns from one class of transitive verbs:

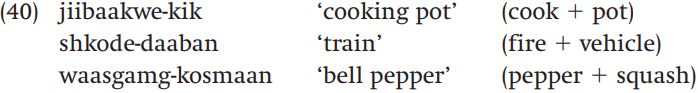

And Nishnaabemwin also has compounds, which differ from the forms in (38) by being composed of two independent stems (Valentine 2001: 516–17):

One thing that is striking about the morphological system of Nishnaabemwin is the overall complexity of words: words rarely consist of a single morpheme, and frequently consist of many morphemes.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)