Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Historical changes in productivity

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

67-4

19-1-2022

1068

Historical changes in productivity

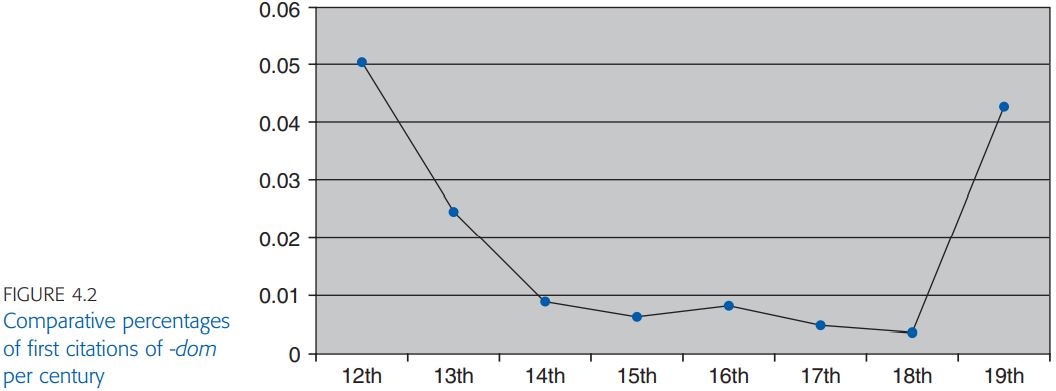

It should not come as a surprise at this point that lexeme formation processes may change their degree of productivity over time. Consider, for example, the suffix -dom in English, which attaches (mostly) to nouns and forms nouns. We find it in such words as chiefdom, fandom, and stardom. Not too much work has been done on methods of measuring productivity over time, but here is one very rough idea of how to do it. With some care, it’s possible to find all the words in the OED with the suffix -dom and take note of when they were first cited (in other words, the year of the first quotation the OED gives for their use). We can then count up how many -dom words were first cited in each century. If we also know how many citations there are in the OED for each century (not every century has the same number of citations), we can calculate what percentage of them are first citations with -dom. For example, if the OED gives 28,698 citations dating from the thirteenth century, and seven of them are the first citations of words with -dom, then the -dom citations represent 0.0243% of all the citations. I’ve calculated these percentages for each century, and then plotted them on a graph, as you can see in figure 4.2.

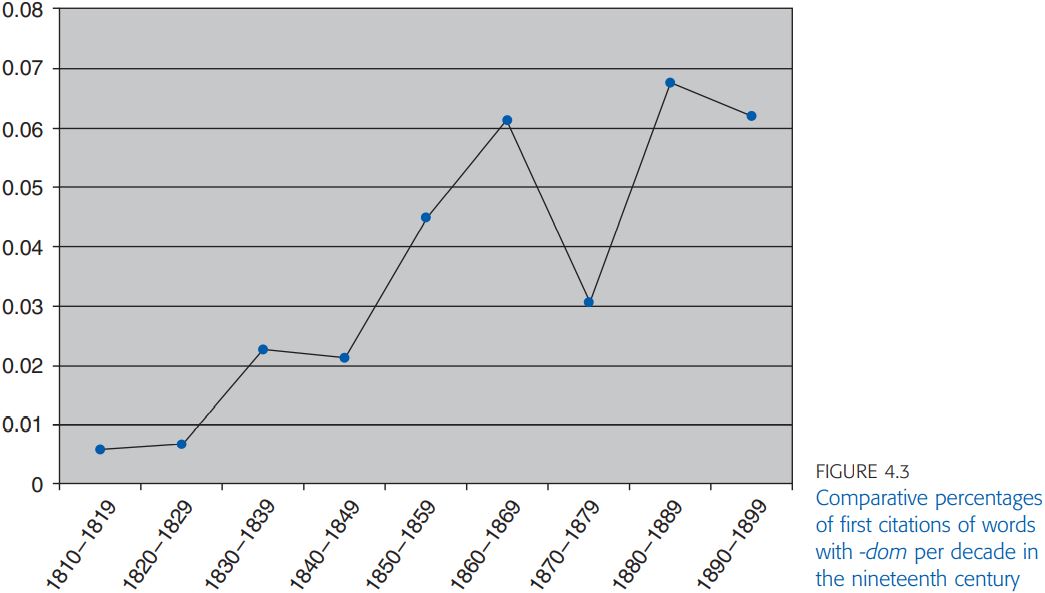

The suffix -dom is a very old one, going back to the beginnings of English, and indeed further back into the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family, from which English descends.1 We can see that after an initially very productive period in the twelfth century, -dom seems to have dropped off in productivity from the fourteenth through the eighteenth centuries. But its productivity rises again precipitously in the nineteenth century. In fact, we can see from figure 4.3 that if we look in detail at the percentage of first citations per decade in the nineteenth century, the suffix gained steadily in productivity as the century progressed (with an odd blip in the 1870s), and peaked in the 1880s.

Exactly why the productivity of the suffix should start to rise after centuries of minimal productivity is unclear. Wentworth (1941) notices the same trend that I’ve shown here, and points out that particular nineteenth-century authors seem especially prone to coin new words with the suffix: Thomas Carlyle and William Makepeace Thackeray in Britain, Mark Twain and Sinclair Lewis in the United States. But whether they are the cause of the rise or a reflection of something that was happening in the language at large is impossible to say. Bauer (2001) points out that in the nineteenth century, the kind of bases available to the suffix -dom seemed to expand drastically. Where it was confined for many centuries to bases referring to important types of people (lord, king, master, pope, earl, but also martyr and witch) or a few adjectives (wise, rich, free), in the nineteenth century it began to appear with more frequency on names for animals (puppy, dog, butterfly, centaur) and a wide variety of common nouns (school, twaddle, leaf, magazine, jelly, cotton, fossil). But why, exactly, its range of bases expanded at this point is still a mystery.

By the way, when he wrote in the early 1940s Wentworth was convinced that the productivity of -dom did not drop from the turn of the twentieth century on, as figure 4.3 suggests: in addition to scrutinizing the OED, as I have done here, he checked through other dictionaries and collected his own examples, and his study turned up quite a few words. Still, the OED has not added a huge number of examples since Wentworth wrote his article, and it appears that although -dom is still quite productive, it does not now enjoy the enormous popularity it did during the 1880s.

This is just one suffix in just one language, but we would expect that other word formation processes could be tracked in a similar way, showing the different processes most active in a language at any given time.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)