Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

What do affixes mean?

المؤلف:

Rochelle Lieber

المصدر:

Introducing Morphology

الجزء والصفحة:

39-3

15-1-2022

3837

What do affixes mean?

When we made the distinction between affixes and bound bases above, we did so on the basis of a rather vague notion of semantic robustness; bound bases in some sense had more meat to them than affixes did. Let us now attempt to make that idea a bit more precise by looking at typical meanings of affixes.

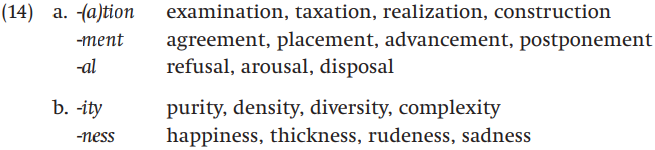

In some cases, affixes seem to have not much meaning at all. Consider the suffixes in (14):

Beyond turning verbs into nouns with meanings like ‘process of X-ing’ or ‘result of X-ing’, where X is the meaning of the verb, it’s not clear that the suffixes -(a)tion, -ment, and -al add much of any meaning at all. Similarly with -ity and -ness, these don’t carry much semantic weight of their own, aside from what comes with turning adjectives into nouns that mean something like ‘the abstract quality of X’, where X is the base adjective. Affixes like these are sometimes called transpositional affixes, meaning that their primary function is to change the category of their base without adding any extra meaning.

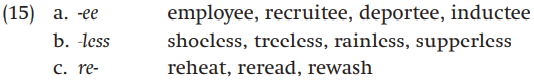

Contrast these, however, with affixes like those in (15):

These affixes seem to have more semantic meat on their bones, so to speak: -ee on a verb indicates a person who undergoes an action; -less means something like ‘without’; and re- means something like ‘again’.

Languages frequently have affixes (or other morphological processes) that fall into common semantic categories. Among those categories are:

•personal affixes: These are affixes that create ‘people nouns’ either from verbs or from nouns. Among the personal affixes in English are the suffix -er which forms agent nouns (the ‘doer’ of the action) like writer or runner and the suffix -ee which forms patient nouns (the person the action is done to).

•negative and privative affixes: Negative affixes add the meaning ‘not’ to their base; examples in English are the prefixes un-, in-, and non- (unhappy, inattentive, non-functional). Privative affixes mean something like ‘without X’; in English, the suffix -less (shoeless, hopeless) is a privative suffix, and the prefix de- has a privative flavor as well (for example, words like debug or debone mean something like ‘cause to be without bugs/bones’).

•prepositional and relational affixes: Prepositional and relational affixes often convey notions of space and/or time. Examples in English might be prefixes like over- and out- (overfill, overcoat, outrun, outhouse).

quantitative affixes: These are affixes that have something to do with amount. In English we have affixes like -ful (handful, helpful) and multi- (multifaceted). Another example might be the prefix re-that means ‘repeated’ action (reread), which we can consider quantitative if we conceive of a repeated action as being done more than once.

•evaluative affixes: Evaluative affixes consist of diminutives, affixes that signal a smaller version of the base (for example in English -let as in booklet or droplet) and augmentatives, affixes that signal a bigger version of the base. The closest we come to augmentative affixes in English are prefixes like mega- (megastore, megabite). The Native American language Tuscarora (Iroquoian family) has an augmentative suffix -ʔoʔy that can be added to nouns to mean ‘a big X’; for example takó:-ʔoʔy means ‘a big cat’ (Williams 1976: 233). Diminutives and augmentatives frequently bear other nuances of meaning. For example, diminutives often convey affection, or endearment. Augmentatives sometimes have pejorative overtones.

Note that some semantically contentful affixes change syntactic category as well; for example, the suffixes -er and -ee change verbs to nouns, and the prefix de- changes nouns to verbs. But semantically contentful affixes need not change syntactic category. The suffixes -hood and -dom, for example, do not (childhood, kingdom), and by and large prefixes in English do not change syntactic category

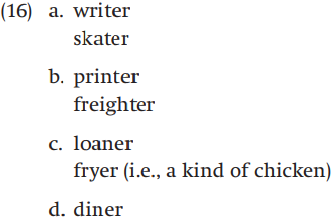

So far we have been looking at suffixes and prefixes whose meanings seem to be relatively clear. Things are not always so simple, though. Let’s look more closely at the suffix -er in English, which we said above formed agent nouns. Consider the following words:

All of these words seem to be formed with the same suffix. Look at each group of words and try to characterize what their meanings are. Does -er seem to have a consistent meaning?

It’s rather hard to see what all of these have in common. The words in (16a) are indeed all agent nouns, but the (b) words are instruments, in other words, things that do an action. In American English the (c) words are things as well, but things that undergo the action rather than doing the action (like the patient -ee words discussed above): a loaner is something which is loaned (often a car, in the US), and a fryer is something (a chicken) which is fried. And the word diner in (d) denotes a location (a diner in the US is a specific sort of restaurant). Some morphologists would argue that there are four separate suffixes in English, all with the form -er. But others think that there’s enough similarity among the meanings of -er words in all these cases to merit calling -er a single affix, but one with a cluster of related meanings. All of the forms derived with -er denote concrete nouns, either persons or things, related to their base verbs by participating in the action denoted by the verb, although sometimes in different ways. This cluster of related meanings is called affixal polysemy.

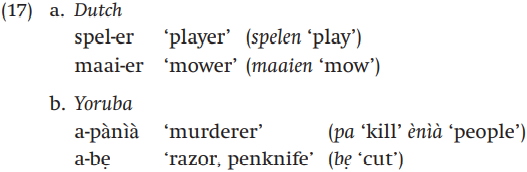

Affixal polysemy is not unusual in the languages of the world. For example, it is not unusual for agents and instruments to be designated by the same suffix. This occurs in Dutch, as the examples in (17a) show (Booij and Lieber 2004), but also in Yoruba (Niger-Congo family), as the examples in (17b) show (Pulleyblank 1987: 978):

The Dutch suffix -er is in fact quite similar to the -er suffix in English in the range of meanings it can express. The Yoruba prefix a- also forms both agents and instrument

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)