Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Syllables Introduction

المؤلف:

Mehmet Yavas̡

المصدر:

Applied English Phonology

الجزء والصفحة:

P131-C6

2025-03-11

295

Syllables

Introduction

The patterns of vowels and consonants we have reviewed thus far have frequently made references to the phonological unit of syllable. The relevance of the unit of syllable in phonological description is shown by rules about the allophonic variations regarding aspiration (i.e. voiceless stops are aspirated at the beginning of stressed syllables); glottalization or glottal stop replacement of /t/ (i.e. /t/ may be optionally glottalized or totally replaced by a glottal stop in syllable-final position); lowering of /ɔ/ to /ɑ/ before /ɹ̣/ (i.e. /ɔ/ can be optionally replaced by /ɑ/ before /ɹ̣/, if the vowel and /ɹ̣/ belong to different syllables); as well as distribution of some sounds, as in the case of /h/ and /ŋ/ (i.e. /h/ is always syllable-initial and never syllable-final, and /ŋ/ is always syllable-final and never syllable-initial).

Beyond its relevance for the phonological rules, syllable has an important role with respect to the phonotactic constraints in languages. This refers to the system of arrangement of sounds and sound sequences. It is on this basis that a speaker of English can judge some new form as a possible or impossible word. For example, both [blɪt] and [bmɪt] are non-existent as English words. If asked to choose between the two, a native speaker of English, without a moment’s hesitation, would go for [blɪt]. The reason for this is that [bl] is a possible onset cluster in English, whereas [bm] is not. This is not to say that no English word can have a [bm] sequence. Words such as submarine [sΛbməɹ̣in] and submission [sΛbmɪʃən] are clear demonstrations of the fact that we can have /m/ after /b/ in English. This, however, is possible only if these two sounds are in different syllables. So the rejection of a word such as [bmɪt] is strictly based on a syllable-related generalization.

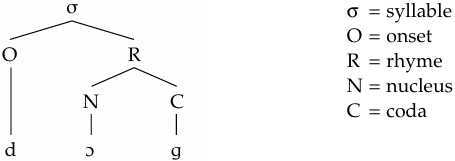

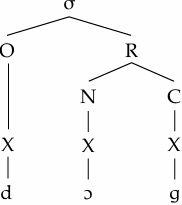

Although we have made numerous references to syllables and syllable position up until this point, we have not dealt with the definition of syllable, nor have we dealt with the question of syllabification. Before we do this, we will look at the hierarchical internal structure of syllable. Earlier (in Phonetics), we suggested a binary split between the onset and the rhyme for syllables. Thus, a monosyllabic word such as dog [dɔg] has the following structure:

The justification for onset–rhyme separation is not hard to find. First of all, rhyming (i.e. whether two words rhyme) is totally based on the vowel/diphthong and anything that follows it (nucleus + optional coda = rhyme); onset is irrelevant. If, on the other hand, we look at the device of alliteration (i.e. the repetition of the same consonant sound(s) at the onset position in two words, as in stem [stεm] and stern [stɝn]), we see that, here, it is the onset that counts and the rhyme is irrelevant. More strong evidence that rhyme is a constituent comes from the stress rules. In several languages (English included) in which the stress is sensitive to the structure of syllables, the structure of the rhyme is the determining factor; onsets do not count.

Also, restrictions between syllabic elements are, overwhelmingly, either within the onset or within the rhyme. For example, as mentioned above, the restriction that a stop cannot be followed by a nasal is valid in the onset (across syllables, this is allowed, e.g. batman, admonish). Similarly, the statement that English does not allow non-homorganic nasal + stop is valid for coda clusters, because while a form such as [lɪmk] is impossible, we can get such non-homorganic sequences across syllables (e.g. kumquat, pumpkin). Another example of a similar phenomenon comes from the sequences of two obstruents with respect to voicing. While it is not difficult to find examples such as cubs [kΛbz] and cups [kΛps] where the sequences of bilabial stops and alveolar fricatives agree in voicing, we do not find words such as [kΛpz] and [kΛbs] with disagreement in voicing. This does not mean that there are no words in English where we put two obstruents with opposite voicing together. Examples such as absurd [æbsɚd], obsolete [Absəlit], and Hudson [hΛdsən] can be easily multiplied. The difference between these two groups of words lies in the tautosyllabic (i.e. in the same syllable) nature of the two obstruents in the former, and the split of the sequence of stop and fricative by a syllable boundary in the latter.

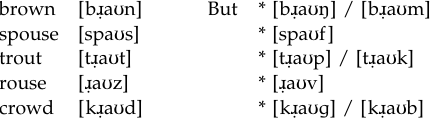

Further attesting the existence of rhyme as a constituent, dependencies between nuclei and codas are commonly found. To give an example from English, we can look at the /aʊ/ nucleus and its relationship with its coda:

What these examples demonstrate is that the coda that follows /aʊ/ has to be alveolar; this nucleus cannot be followed by labial or velar consonants.

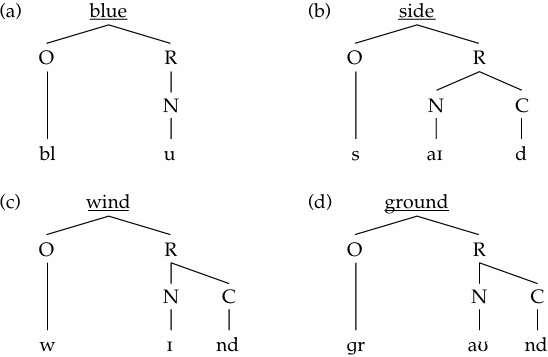

Having made the point that onsets and rhymes should be seen as autonomous units, each with its own constraints on its internal structure, we are now ready to look at the details (for a different view, which argues against the necessity of the rhyme as a unit, see Davis 1988). In the word dog above, the final units of the syllable each contained one segment. However, as we will see shortly in greater detail, there are several other possibilities in English. To give some examples, let us look at the words blue, side, wind, and ground.

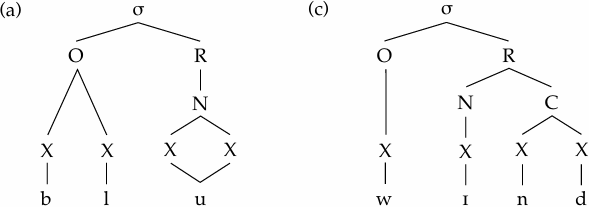

When we look at these representations, we see that several positions are taken by sequences of two segments, and that would make it obvious, for example, that the onset cluster of (a), /bl/, will be longer than the single onset of (b), /s/. While this is true, the representation, as it is, is not sufficient to make any distinction between the nucleus of (a) (/u/, a long vowel) and the nucleus of (c) (/ɪ/, a short vowel). To remedy this situation, we introduce a skeletal tier (i.e. ‘X’) that reveals the timing slots for each unit. Thus, we represent the difference between (a) and (c) in the following manner:

In this revised representation, long vowels and diphthongs will have two timing slots (branching), whereas short vowels will have one (non-branching). Multiple onsets/codas will also be branching. Finally, we give the revised tree of the CVC word dog,

which has a non-branching onset [d] and a branching rhyme [ɔg].

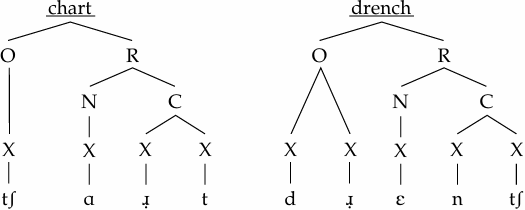

The advantage of the design with skeletal tiers is not only to distinguish branching from non-branching, which, as we will see shortly, is very important in stress assignment rules, but also to help us to deal with segments such as affricates that are phonetically complex but phonologically simple. Consider the following:

Here the clusters are branching (two timing slots) but the phonetically com plex affricates are non-branching (one timing slot)