Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Truncation and stress

المؤلف:

Ingo Plag

المصدر:

Morphological Productivity

الجزء والصفحة:

P164-C6

2025-02-03

691

Truncation and stress

The next problematic point concerning the phonology of -ize is truncation. It is clear that possible bases of -ize may lose final segments, but we have seen that it is still unclear how this can be restricted. Raffelsiefen proposes two auxiliary constraints to account for truncation restrictions. The first one, already mentioned above, dictates that two syllables of the base must remain intact, the second one "requires all onsets in the base to correspond to identical onsets in the derived form" (Raffelsiefen 1996:200, note 19). Unfortunately, these constraints are not discussed in detail in her article, and it is left unclear how they should be incorporated. However, our earlier remarks have already shown that the first constraint is inadequate. The second one is more promising, however.

It can be observed that only entire word-final rhymes and not just word-final consonants may be truncated. In Raffelsiefen's model the deletion of a single consonantal coda is made impossible by other constraints, like *VV, which is evoked to rule out forms like *emphasiize. However, it is still left unclear as to why the final segment in complex codas is never deleted (cf. the discussion of words like potentize/*potenize above). In a preliminary fashion these facts can be generalized as in (1):

(1)

We may now turn to the stress clash constraint. Both Goldsmith (1990:270ff) and Raffelsiefen (1996) point out that stress clashes are generally avoided in possible words.1 So far, we have frequently referred to this constraint, but, in view of the numerous counterexamples, its exact formulation and status remain problematic.

I assume that we have to distinguish three degrees of stress in English. Syllables may have primary stress, non-primary (i.e. secondary) stress,2 or no stress (cf., e.g., Giegerich 1985). This trichotomy is corroborated by both phonological and phonetic facts (see Giegerich 1992). The stress behavior of -ize derivatives can now be largely predicted from the segmental structure of the suffix. Since the syllabic structure of -ize involves a branching rhyme with a diphthong, the suffix will attract secondary stress.3 Given that stress clashes tend to be avoided in complex words, we can predict that -ize usually does not occur after stressed syllables. Counterexamples like banálìze and routìnìze,4* are, however, occasionally coined, which shows that speakers may violate this constraint if no other possibility is available to avoid the clash (for example through truncation). Although the stress clash constraint seems to be important and necessary, Raffelsiefen cannot account for some derivatives like ràdiòìze which are impossible formations in her model, because they violate both *VV and * CLASH, whereas the corresponding truncated form *rádiìze would only violate *VV and the lower ranked IDENT constraint. Again, the con straints as proposed by Raffelsiefen do not make the correct predictions.

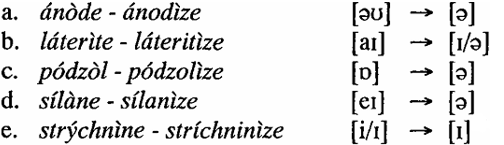

Another stress-related problem is that with some isolated forms involving secondary ultimate stress, -ize attachment may lead to the destressing of secondarily stressed syllables. Consider the following pairs:

(2)

[ɪ]5

Similar alternations are discussed by Kettemann who proposes individual rules of vowel reduction ([ɑ] ↔ [ə], [aɪ] ↔ [ə], [æ] ↔ [ə]), but explains them as instances of the Auxiliary Vowel Reduction Rule (Halle and Key ser 1971:35) in connection with SPE's Vowel Reduction Rule (1968:126). In essence, these alternations seem not to be specific to -ize derivatives but follow from general principles of stress assignment and foot construction in English (see also Giegerich 1992, Goldsmith 1990:259). In other words, the forms in (2) are more fully integrated into the general metrical system of English than forms that feature two adjacent stressed syllables. However, not all base-final secondarily stressed syllables are affected by destressing, but only those that end in a consonant. For example, ghettoize and radioize (and all other pertinent forms) preserve their secondary stress. In other words, we are faced with another incidence where the segmental structure interacts with the metrical structure in an interesting way.

Note that the syllable which carries primary stress is never reduced or destressed. This is what one would expect if stress shift were possible, but, apart from some rare exceptions, the main stress of the base word is never shifted by productive -ize attachment. There are only five forms in the corpus of 284 20th century neologisms in which the main stress of the base seems to be altered, namely bàcterìze, lyóphilìze, lysógenìze, multìmerìze, and phagocy̒tìze.

1 For Goldsmith (1990:271), the prohibition of stress clashes is dependent on an intervening word boundary. Raffelsiefen argues against this dependency on the grounds that it also holds for cases where stem allomorphy is involved, i.e. where there is only a morpheme-boundary. Furthermore, she claims that stress clashes are historically often unstable, as shown by the replacement of quantity-sensitive stress by alternating stress in words like mobile, abdomen, advertise and the like. We will return to this issue below.

2 I do not use 'secondary' in the sense of SPE stress 2, but simply as a label for syllables that have non-primary stress. For a detailed criticism of the SPE stress numerology see e.g. Hogg and McCully (1987).

3 We ignore here the possibility that -ize may receive primary stress. See below for discussion.

4 The stress patterns indicated follow the information given in the OED. Note, however, that, at least in American English, routinize is pronounced usually with primary stress on the first syllable, followed by an unstressed syllable. In other words, there is a stress shift. Note also that there are at least two dialect clusters which exhibit primary stress on -ize, Hiberno-English and Caribbean English. Dialectal variation in stress patterns of derived words in general is certainly in need of further investigation, but will not be dealt with systematically here.

5 I adopt here the pronunciations given by the OED. Some speakers prefer the pronunciation [stɹɪknaɪn] for the base word, but this does not have any effect on the pronunciation of the derived verb, because even these speakers pronounce the verb [stɹɪknɪnaɪz]. For these speakers strychninize patterns like lateritize in (2b).

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)