تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Coupled pendulums

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 49

2024-06-29

1490

Finally, we should emphasize that not only do modes exist for complicated continuous systems, but also for very simple mechanical systems. A good example is the system of two coupled pendulums discussed in the preceding chapter. In that chapter it was shown that the motion could be analyzed as a superposition of two harmonic motions with different frequencies. So even this system can be analyzed in terms of harmonic motions or modes. The string has an infinite number of modes and the two-dimensional surface also has an infinite number of modes. In a sense it is a double infinity, if we know how to count infinities. But a simple mechanical thing which has only two degrees of freedom, and requires only two variables to describe it, has only two modes.

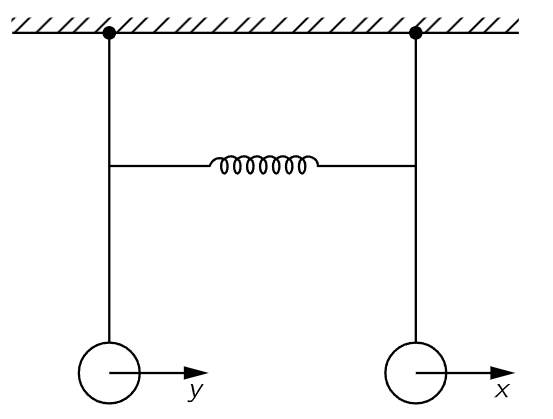

Fig. 49–5. Two coupled pendulums.

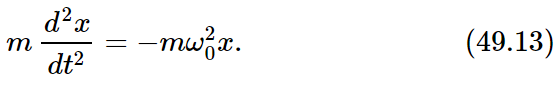

Let us make a mathematical analysis of these two modes for the case where the pendulums are of equal length. Let the displacement of one be x, and the displacement of the other be y, as shown in Fig. 49–5. Without a spring, the force on the first mass is proportional to the displacement of that mass, because of gravity. There would be, if there were no spring, a certain natural frequency ω0 for this one alone. The equation of motion without a spring would be

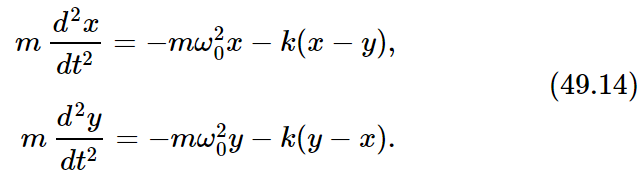

The other pendulum would swing in the same way if there were no spring. In addition to the force of restoration due to gravitation, there is an additional force pulling the first mass. That force depends upon the excess distance of x over y and is proportional to that difference, so it is some constant which depends on the geometry, times (x−y). The same force in reverse sense acts on the second mass. The equations of motion that have to be solved are therefore

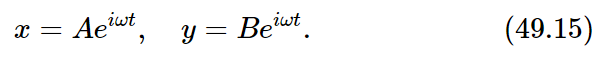

In order to find a motion in which both of the masses move at the same frequency, we must determine how much each mass moves. In other words, pendulum x and pendulum y will oscillate at the same frequency, but their amplitudes must have certain values, A and B, whose relation is fixed. Let us try this solution:

If these are substituted in Eqs. (49.14) and similar terms are collected, the results are

The equations as written have had the common factor eiωt removed and have been divided by m.

Now we see that we have two equations for what looks like two unknowns. But there really are not two unknowns, because the whole size of the motion is something that we cannot determine from these equations. The above equations can determine only the ratio of A to B, but they must both give the same ratio. The necessity for both of these equations to be consistent is a requirement that the frequency be something very special.

In this particular case this can be worked out rather easily. If the two equations are multiplied together, the result is

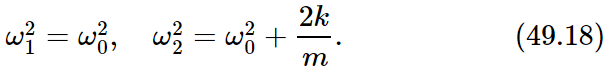

The term AB can be removed from both sides unless A and B are zero, which means there is no motion at all. If there is motion, then the other terms must be equal, giving a quadratic equation to solve. The result is that there are two possible frequencies:

Furthermore, if these values of frequency are substituted back into Eq. (49.16), we find that for the first frequency A=B, and for the second frequency A=−B. These are the “mode shapes,” as can be readily verified by experiment.

It is clear that in the first mode, where A=B, the spring is never stretched, and both masses oscillate at the frequency ω0, as though the spring were absent. In the other solution, where A=−B, the spring contributes a restoring force and raises the frequency. A more interesting case results if the pendulums have different lengths. The analysis is very similar to that given above, and is left as an exercise for the reader.

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء العامة

الاكثر قراءة في الفيزياء العامة

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)