تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Simultaneity

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 15

2024-02-24

2104

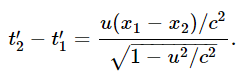

In an analogous way, because of the difference in time scales, the denominator expression is introduced into the fourth equation of the Lorentz transformation. The most interesting term in that equation is the ux/c2 in the numerator, because that is quite new and unexpected. Now what does that mean? If we look at the situation carefully, we see that events that occur at two separated places at the same time, as seen by Moe in S′, do not happen at the same time as viewed by Joe in S. If one event occurs at point x1 at time t0 and the other event at x2 and t0 (the same time), we find that the two corresponding times t′1 and t′2 differ by an amount

This circumstance is called “failure of simultaneity at a distance,” and to make the idea a little clearer let us consider the following experiment.

Suppose that a man moving in a space ship (system S′) has placed a clock at each end of the ship and is interested in making sure that the two clocks are in synchronism. How can the clocks be synchronized? There are many ways. One way, involving very little calculation, would be first to locate exactly the midpoint between the clocks. Then from this station we send out a light signal which will go both ways at the same speed and will arrive at both clocks, clearly, at the same time. This simultaneous arrival of the signals can be used to synchronize the clocks. Let us then suppose that the man in S′ synchronizes his clocks by this particular method. Let us see whether an observer in system S would agree that the two clocks are synchronous. The man in S′ has a right to believe they are, because he does not know that he is moving. But the man in S reasons that since the ship is moving forward, the clock in the front end was running away from the light signal, hence the light had to go more than halfway in order to catch up; the rear clock, however, was advancing to meet the light signal, so this distance was shorter. Therefore, the signal reached the rear clock first, although the man in S′

thought that the signals arrived simultaneously. We thus see that when a man in a space ship thinks the times at two locations are simultaneous, equal values of t′ in his coordinate system must correspond to different values of t in the other coordinate system!

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

الاكثر قراءة في مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)