تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Translations

المؤلف:

Richard Feynman, Robert Leighton and Matthew Sands

المصدر:

The Feynman Lectures on Physics

الجزء والصفحة:

Volume I, Chapter 11

2024-02-08

1513

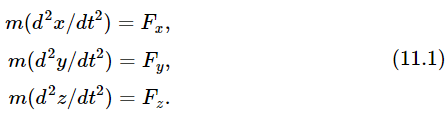

We shall limit our analysis to just mechanics, for which we now have sufficient knowledge. In previous chapters we have seen that the laws of mechanics can be summarized by a set of three equations for each particle:

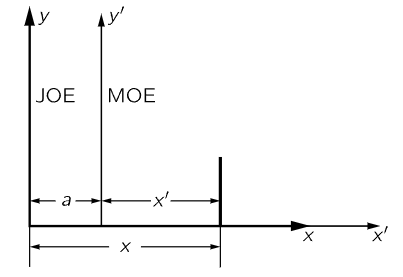

Now this means that there exists a way to measure x, y, and z on three perpendicular axes, and the forces along those directions, such that these laws are true. These must be measured from some origin, but where do we put the origin? All that Newton would tell us at first is that there is some place that we can measure from, perhaps the center of the universe, such that these laws are correct. But we can show immediately that we can never find the center, because if we use some other origin it would make no difference. In other words, suppose that there are two people—Joe, who has an origin in one place, and Moe, who has a parallel system whose origin is somewhere else (Fig. 11–1). Now when Joe measures the location of the point in space, he finds it at x, y, and z (we shall usually leave z out because it is too confusing to draw in a picture). Moe, on the other hand, when measuring the same point, will obtain a different x (in order to distinguish it, we will call it x′), and in principle a different y, although in our example they are numerically equal. So we have

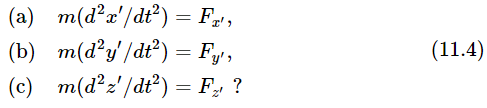

Now in order to complete our analysis we must know what Moe would obtain for the forces. The force is supposed to act along some line, and by the force in the x–direction we mean the part of the total which is in the x–direction, which is the magnitude of the force times this cosine of its angle with the x–axis. Now we see that Moe would use exactly the same projection as Joe would use, so we have a set of equations

These would be the relationships between quantities as seen by Joe and Moe.

Fig. 11–1. Two parallel coordinate systems.

The question is, if Joe knows Newton’s laws, and if Moe tries to write down Newton’s laws, will they also be correct for him? Does it make any difference from which origin we measure the points? In other words, assuming that equations (11.1) are true, and the Eqs. (11.2) and (11.3) give the relationship of the measurements, is it or is it not true that

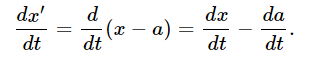

In order to test these equations, we shall differentiate the formula for x′ twice. First of all

Now we shall assume that Moe’s origin is fixed (not moving) relative to Joe’s; therefore a is a constant and da/dt=0, so we find that

(We also suppose that the masses measured by Joe and Moe are equal.) Thus the acceleration times the mass is the same as the other fellow’s. We have also found the formula for Fx′, for, substituting from Eq. (11.1), we find that

Fx′ = Fx.

Therefore, the laws as seen by Moe appear the same; he can write Newton’s laws too, with different coordinates, and they will still be right. That means that there is no unique way to define the origin of the world, because the laws will appear the same, from whatever position they are observed.

This is also true: if there is a piece of equipment in one place with a certain kind of machinery in it, the same equipment in another place will behave in the same way. Why? Because one machine, when analyzed by Moe, has exactly the same equations as the other one, analyzed by Joe. Since the equations are the same, the phenomena appear the same. So the proof that an apparatus in a new position behaves the same as it did in the old position is the same as the proof that the equations when displaced in space reproduce themselves. Therefore, we say that the laws of physics are symmetrical for translational displacements, symmetrical in the sense that the laws do not change when we make a translation of our coordinates. Of course, it is quite obvious intuitively that this is true, but it is interesting and entertaining to discuss the mathematics of it.

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

الاكثر قراءة في الميكانيك

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)