Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Language shift in Oberwart, Austria

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

251-12

2024-01-02

832

Language shift in Oberwart, Austria

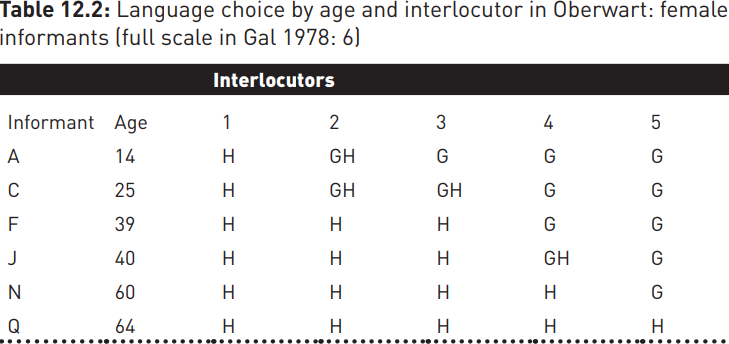

After four centuries of stable German/Hungarian diglossia, the Austrian border town of Oberwart saw a decisive shift in favor of the H language, German, in the post-war period, as can be seen in the table below. The implicational scale of female speakers and interlocutors shows increased German use with all interlocutors among younger speakers, with only God still consistently addressed in Hungarian.

Key: G: German; H: Hungarian

Interlocutors: 1 = God; 2 = grandparents and their generation; 3 = parents and their generation; 4 = bilingual government officials; 5 = doctors

The shift in favor of German has been triggered by economic change. While German had become associated with the status of industrial worker, Hungarian was the traditional language of the peasant farmer. Until the Second World War, neither status dominated: while workers often had more disposable income, peasants enjoyed the security of land ownership. The post-war consumer boom, however, greatly improved living standards for salaried workers, undermining the relative prestige of the peasant farmer, whose lifestyle now acquired the negative associations of long hours of toil for relatively little reward.

As the two languages came to symbolize the changing statuses of the two lifestyles, bilingual speakers were able to exploit these associations metaphorically in language selection and code-switching: explaining to a neighbor how to fix a car in Hungarian, for example, might be perceived as a friendly tip, while the same information in German, the language of modernity and sophistication, would be taken as expert advice. A switch from Hungarian to German when reprimanding a child would signal a more serious tone, and indicate that the parent was now demanding compliance.

Language shift in Oberwart has no implications for Hungarian across the border in Hungary, where it is healthy, but in cases where shift leaves a language without native speakers it is appropriate to talk of language death. In most cases, death is slow and follows a period of ‘leaky’ diglossia. Only in extreme circumstances – for example, the extermination of 250,000 speakers of the Tasmanian language in the nineteenth century – does it occur suddenly and not from gradual erosion of its functions. Cornish and Manx, for example, both died because speakers increasingly began to use English in domains formerly reserved for the Celtic language, until eventually bilingual speakers chose to raise their children only in English, leaving the threatened language with no new native speakers. Languages never die out because they are somehow ‘not good enough’: they die because their speakers’ economic or other needs induce them to use a dominant language in more and more domains, leaving the obsolescent language with fewer and fewer functions.