Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Language and gender

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

236-11

2024-01-02

659

Language and gender

Of all the findings of modern sociolinguistics, none can have been more intensely debated than what has become known as the sociolinguistic gender pattern (SGP), set out by Trudgill in the following terms:

Hypercorrection

Another meaning of hypercorrection, and a frequent source of language-based comedy in popular drama, is the over-extension of a rule learned by a social climber to a linguistic environment where it does not apply. Before British English speakers were as aware as they are today of each others’ regional accents, it was claimed, for example, that northern English speakers living in the south and aspiring to the prestigious RP accent would pronounce some words like butcher with the southern STRUT vowel, i.e. as  rather than

rather than  , because they erroneously assumed that all instances of

, because they erroneously assumed that all instances of  could be replaced by

could be replaced by  in RP. While this strategy works fine for come and rub, it does not for butcher or pull, where northerners and RP speakers have the same vowel.

in RP. While this strategy works fine for come and rub, it does not for butcher or pull, where northerners and RP speakers have the same vowel.

Dramatists have seen comic potential in the propensity of Cockneys – traditional London English speakers – to drop h at the beginning of words. Fans of the cult 1960s TV adventure puppet show Thunderbirds will recall, for example, how Parker, an ex-jailbird now working as manservant to the aristocrat Lady Penelope, would attempt to use higher status speech by reinserting the lost initial h’s of Cockney English, usually in the wrong places, e.g. ‘I must apologize for the hunconventional entrance, m’Lady, but I ‘ad to happre’end ‘im some’ow’.

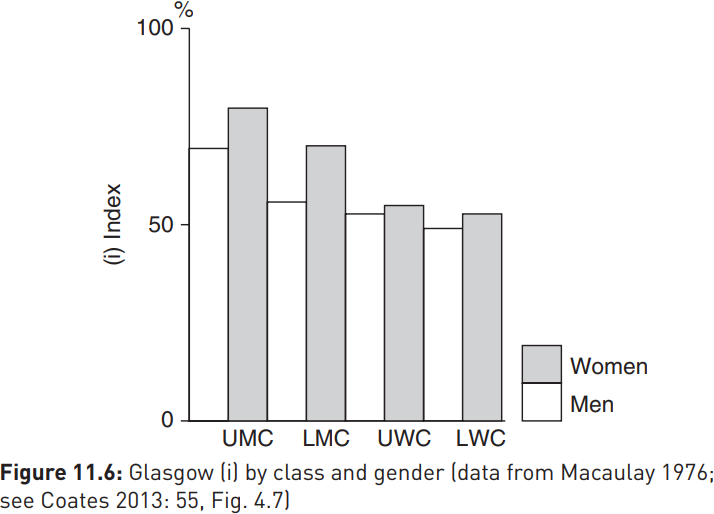

Trudgill is not, of course, claiming that women speak ‘better’ than men, nor, indeed, that men and women have different languages. Gender-based differences in speech, with the exception of those imposed by the grammar (for example, a male Russian says ja sidjel ‘I sat’ but a female would say ja sidjela), are generally a matter of more or less, with the genders using the same forms in different proportions. But women nonetheless consistently appear to use more prestige forms than men do. Macaulay’s (1976) data for the (i) variable in Glasgow, for example, suggest that women’s use of prestige variants corresponds broadly to that of men in the social class immediately above them:

Explanations for this remarkably consistent finding have appealed variously to women’s traditionally greater role in the rearing and education of children, to their purportedly greater need to assert status through language, given a generally subordinate social position, and to men’s greater subjection to workplace vernacular norms.

A self-evaluation test from the Norwich survey suggested that attitudinal factors may also play a part. At the end of interview, Trudgill told his informants that he would say some words in two different ways, and asked them to identify (a) the ‘correct’ pronunciation and (b) the pronunciation they themselves used most of the time. Informants had no difficulty recognizing that [tju:n] rather than [tu:n] was the standard pronunciation of tune, for example, and were generally accurate in the identification of their own usage (determined by Trudgill on the basis of the form they had used more than half the time in casual style in the recorded interview).

But an interesting pattern obtained among those who, according to the available data, answered the second question wrongly: here the over-reporters – those who thought they used the standard form more than they actually did – were mostly female, while the under-reporters – who used fewer vernacular forms than they thought they did – were mostly male, irrespective of social class. Trudgill suggested that many men genuinely believed they used these variants more than they did because, perhaps at a subconscious level since no deception seemed to be involved, they actually liked them, even though they were stigmatized low-status forms. These variants had covert prestige by virtue of their association with working-class speakers, the stereotypically ‘rough and tough’ nature of whose working lives was arguably more attractive to men than to women, who identified more strongly with overtly prestigious forms.