Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Suprasegmentals

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

77-4

2023-12-13

667

Suprasegmentals

The descriptors and symbols introduced so far provide a good basis for analysing the sounds of any language. The IPA enables us, moreover, to divide up connected speech into individual sounds, or segments, which we can present in ordered sequence, for example:

But the neat boundaries between phones that such sequences imply are something of a fiction. Speech sounds roll into one another, and one sound can significantly influence its neighbours. Take the vowel in ran in the example above, for instance, which for most British English speakers sounds slightly different from that of rat, having a slight nasal quality that the latter lacks. This is because speakers generally lower the velum in readiness for the nasal consonant [n] well before the vowel has completed, with the result that nasality affects both segments and cannot be seen as the exclusive property of the consonant, as the broad linear transcription above suggests. A number of other phenomena can only be analyzed above and beyond the level of the segment: these are known, appropriately enough, as suprasegmentals.

Segments of speech

• Speech is continuous and does not divide neatly into discrete sounds, in the way that written words and sentences are built from individual letters and spaces. For this reason phoneticians refer to their divisions of the speech chain as segments.

• IPA symbols can be used to represent the segments of a speech chain on the page, e.g. cat [kat].

One type of suprasegmental is stress, which refers to the relative prominence of one syllable over another in a word. In English, for example, the sequence of segments in the noun increase and its corresponding verb increase is the same, but the two forms sound different because a different syllable (underlined here) is stressed in each case. An unstressed vowel is sometimes reduced in quality, being given less prominence and articulatory effort. The first syllable in photograph for example has the diphthong  , but in unstressed position in photography this reduces to

, but in unstressed position in photography this reduces to  . Stress is generally indicated by a raised diacritic before the stressed syllable, so for the examples above photograph

. Stress is generally indicated by a raised diacritic before the stressed syllable, so for the examples above photograph  but photography

but photography  . Stress is a relative concept, referring to the prominence of one syllable with respect to another, and involves a combination of pitch (stressed syllables have a higher frequency or pitch than unstressed ones), loudness or intensity and possibly vowel length. Length itself is also a relative rather than absolute concept, or an inherent quality of a speech sound itself. The vowels

. Stress is a relative concept, referring to the prominence of one syllable with respect to another, and involves a combination of pitch (stressed syllables have a higher frequency or pitch than unstressed ones), loudness or intensity and possibly vowel length. Length itself is also a relative rather than absolute concept, or an inherent quality of a speech sound itself. The vowels  caught and

caught and  in cart, for example, are viewed as long vowels because English speakers generally pronounce them longer than vowels such as

in cart, for example, are viewed as long vowels because English speakers generally pronounce them longer than vowels such as  and [a], but it is important to remember here that one speaker’s

and [a], but it is important to remember here that one speaker’s  may be shorter than another’s [a].

may be shorter than another’s [a].

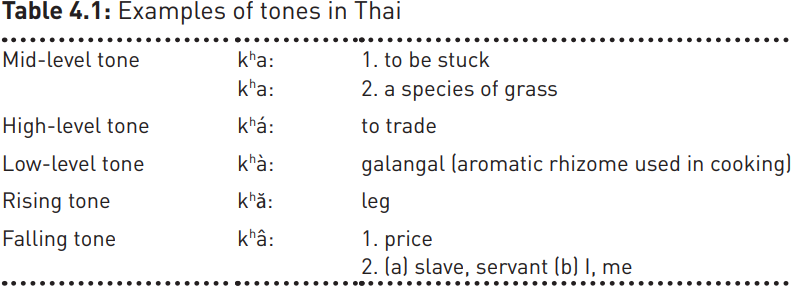

Other important suprasegmental phenomena include intonation and tone, both of which involve changes in pitch within a word or sentence. For example, a simple English sentence like You see him every Saturday would be pronounced with a falling intonation if uttered as a statement, but with a rising intonation at the end if intended as question (You see him every Saturday?). Orthographically, question marks can provide a rough and ready indication of rising intonation, but in most cases readers have to deduce the appropriate intonation for themselves, as conventional writing lacks the resources to make intonation patterns clear. Linguists generally indicate only as much information as the context demands, either via intonation contour lines above the speech string or arrows after the relevant sequence to show the intonation pattern involved, for example a fall ↘; a rise ↗, or a rise–fall ↗↘. In tone languages word-level intonation is important for distinguishing meaning. In Thai, for example, the same sequence of segments uttered with a level, falling or rising tone will have a completely different meaning, as this example (taken from Blake 2008: 139) illustrates: