تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

Simplicial Homology Groups-Connectedness and H0(K)

المؤلف:

David R. Wilkins

المصدر:

Algebraic Topology

الجزء والصفحة:

69-72

28-6-2017

1673

Lemma 1.1 Let K be a simplicial complex. Then K can be partitioned into pairwise disjoint subcomplexes K1, K2, . . . , Kr whose polyhedra are the connected components of the polyhedron |K| of K.

Proof Let X1, X2, . . . , Xr be the connected components of the polyhedron of K, and, for each j, let Kj be the collection of all simplices σ of K for which σ ⊂ Xj . If a simplex belongs to Kj for all j then so do all its faces.

Therefore K1, K2, . . . , Kr are subcomplexes of K. These subcomplexes are pairwise disjoint since the connected components X1, X2, . . . , Xr of |K| are

pairwise disjoint. Moreover, if σ ∈ K then σ ⊂ Xj for some j, since σ is a connected subset of |K|, and any connected subset of a topological space is contained in some connected component. But then σ ∈ Kj . It follows that

K = K1 ∪ K2 ∪ · · · ∪ Kr and |K| = |K1| ∪ |K2| ∪ · · · ∪ |Kr|, as required.

The direct sum A1⊕A2⊕· · ·⊕Ar of additive Abelian groups A1, A2, . . . , Ar is defined to be the additive group consisting of all r-tuples (a1, a2, . . . , ar) with ai ∈ Ai for i = 1, 2, . . . , r, where

(a1, a2, . . . , ar) + (b1, b2, . . . , br) ≡ (a1 + b1, a2 + b2, . . . , ar + br).

Lemma 1.2 Let K be a simplicial complex. Suppose that K = K1 ∪ K2 ∪· · · ∪ Kr, where K1, K2, . . . Kr are pairwise disjoint. Then

Hq(K) ∼= Hq(K1) ⊕ Hq(K2) ⊕ · · · ⊕ Hq(Kr) for all integers q.

Proof We may restrict our attention to the case when 0 ≤ q ≤ dim K, since Hq(K) = {0} if q < 0 or q > dim K. Now any q-chain c of K can be expressed uniquely as a sum of the form c = c1 + c2 + · · · + cr, where cj is a q-chain of Kj for j = 1, 2, . . . , r. It follows that

Cq(K) ≅ Cq(K1) ⊕ Cq(K2) ⊕ · · · ⊕ Cq(Kr).

Now let z be a q-cycle of K (i.e., z ∈ Cq(K) satisfies ∂q(z) = 0). We can express z uniquely in the form z = z1 + z2 + · · · + zr, where zj is a q-chain of Kj for j = 1, 2, . . . , r. Now

0 = ∂q(z) = ∂q(z1) + ∂q(z2) + · · · + ∂q(zr),

and ∂q(zj ) is a (q−1)-chain of Kj for j = 1, 2, . . . , r. It follows that ∂q(zj ) = 0 for j = 1, 2, . . . , r. Hence each zj is a q-cycle of Kj , and thus

Zq(K) ≅ Zq(K1) ⊕ Zq(K2) ⊕ · · · ⊕ Zq(Kr).

Now let b be a q-boundary of K. Then b = ∂q+1(c) for some (q + 1)- chain c of K. Moreover c = c1 + c2 + · · · cr, where cj ∈ Cq+1(Kj ). Thus b = b1 + b2 + · · · br, where bj ∈ Bq(Kj ) is given by bj = ∂q+1cj for j = 1, 2, . . . , r. We deduce that

Bq(K) ≅ Bq(K1) ⊕ Bq(K2) ⊕ · · · ⊕ Bq(Kr).

It follows from these observations that there is a well-defined isomorphism

ν: Hq(K1) ⊕ Hq(K2) ⊕ · · · ⊕ Hq(Kr) → Hq(K)

which maps ([z1], [z2], . . . , [zr]) to [z1 + z2 + · · · + zr], where [zj] denotes the

homology class of a q-cycle zj of Kj for j = 1, 2, . . . , r.

Let K be a simplicial complex, and let y and z be vertices of K. We say that y and z can be joined by an edge path if there exists a sequence v0, v1, . . . , vm of vertices of K with v0 = y and vm = z such that the line segment with endpoints vj−1 and vj is an edge belonging to K for j = 1, 2, . . . , m.

Lemma 1.3 The polyhedron |K| of a simplicial complex K is a connected topological space if and only if any two vertices of K can be joined by an edge path.

Proof It is easy to verify that if any two vertices of K can be joined by an edge path then |K| is path-connected and is thus connected. (Indeed any two points of |K| can be joined by a path made up of a finite number of straight line segments.)

We must show that if |K| is connected then any two vertices of K can be joined by an edge path. Choose a vertex v0 of K. It suffices to verify that every vertex of K can be joined to v0 by an edge path.

Let K0 be the collection of all of the simplices of K having the property that one (and hence all) of the vertices of that simplex can be joined to v0 by an edge path. If σ is a simplex belonging to K0 then every vertex of σ can be joined to v0 by an edge path, and therefore every face of σ belongs to K0.

Thus K0 is a subcomplex of K. Clearly the collection K1 of all simplices of K which do not belong to K0 is also a subcomplex of K. Thus K = K0 ∪ K1, where K0 ∩ K1 = ∅, and hence |K| = |K0| ∪ |K1|, where |K0| ∩ |K1| = ∅.

But the polyhedra |K0| and |K1| of K0 and K1 are closed subsets of |K|. It follows from the connectedness of |K| that either |K0| = ∅ or |K1| = ∅. But v0 ∈ K0. Thus K1 = ∅ and K0 = K, showing that every vertex of K can be joined to v0 by an edge path, as required.

Theorem 1.4 Let K be a simplicial complex. Suppose that the polyhedron |K| of K is connected. Then H0(K) ≅Z.

Proof Let u1, u2, . . . , ur be the vertices of the simplicial complex K. Every 0-chain of K can be expressed uniquely as a formal sum of the form

n1〈u1〉 + n2〈u2〉 + · · · + nr〈ur〉

for some integers n1, n2, . . . , nr. It follows that there is a well-defined homomorphism

ε: C0(K) → Z defined by

ε (n1〈u1〉 + n2〈u2〉 + · · · + nr〈ur〉) = n1 + n2 + · · · + nr.

ow ε(∂1(〈y, z〉)) = ε(〈z〉 − 〈y〉) = 0 whenever y and z are endpoints of an edge of K. It follows that ε ◦ ∂1 = 0, and hence B0(K) ⊂ ker ε.

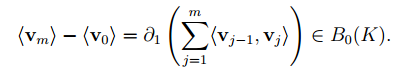

Let v0, v1, . . . , vm be vertices of K determining an edge path. Then

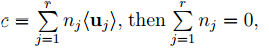

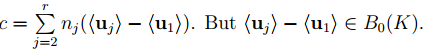

Now |K| is connected, and therefore any pair of vertices of K can be joined by an edge path (Lemma 1.3). We deduce that 〈z〉− 〈y〉∈ B0(K) for all vertices y and z of K. Thus if c ∈ ker ε, where

and hence

c ∈ B0(K). We conclude that ker ε ⊂ B0(K), and hence ker ε = B0(K).

Now the homomorphism ε: C0(K) → Z is surjective and its kernel is B0(K). Therefore it induces an isomorphism from C0(K)/B0(K) to Z.

However Z0(K) = C0(K) (since ∂0 = 0 by definition). Thus H0(K) ≡C0(K)/B0(K) ∼= Z, as required.

On combining Theorem 1.4 with Lemmas 1.1 and 1.2 we obtain immediately the following result.

Corollary 1.5 Let K be a simplicial complex. Then

H0(K) ≅ Z ⊕ Z ⊕ · · · ⊕ Z (r times),

where r is the number of connected components of |K|.

الاكثر قراءة في التبلوجيا

الاكثر قراءة في التبلوجيا

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)