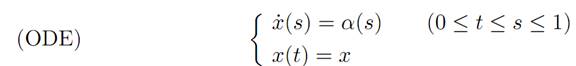

1.1 EXAMPLE 1: DYNAMICS WITH THREE VELOCITIES. Let us begin with a fairly easy problem:

where our set of control parameters is

A = {−1, 0, 1}.

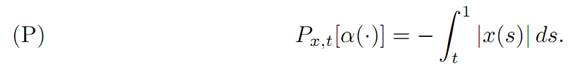

We want to minimize

and so take for our payoff functional

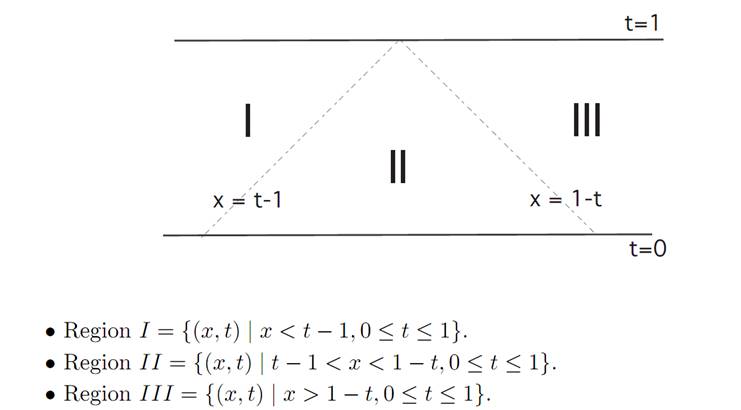

As our first illustration of dynamic programming, we will compute the value function v(x, t) and confirm that it does indeed solve the appropriate Hamilton Jacobi-Bellman equation. To do this, we first introduce the three regions:

We will consider the three cases as to which region the initial data (x, t) lie within.

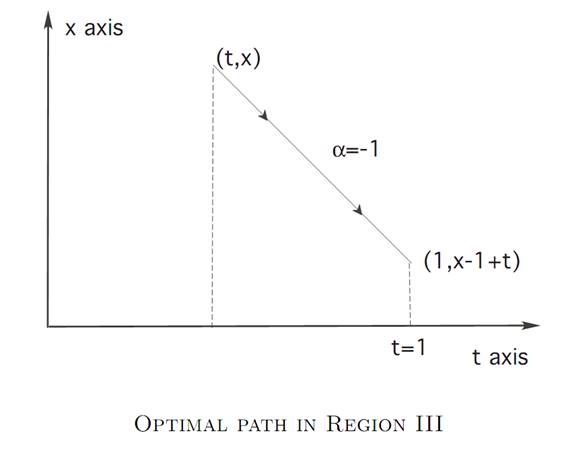

Region III. In this case we should take α ≡ −1, to steer as close to the origin 0 as quickly as possible. (See the next picture.) Then

Region I. In this region, we should take α ≡ 1, in which case we can similarly compute

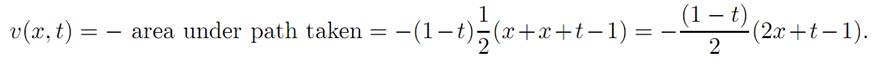

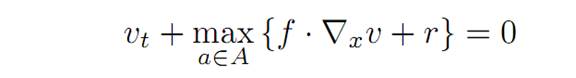

Region II. In this region we take α ≡ ±1, until we hit the origin, after which we take α ≡ 0. We therefore calculate that v(x, t) = −x2/2 in this region.

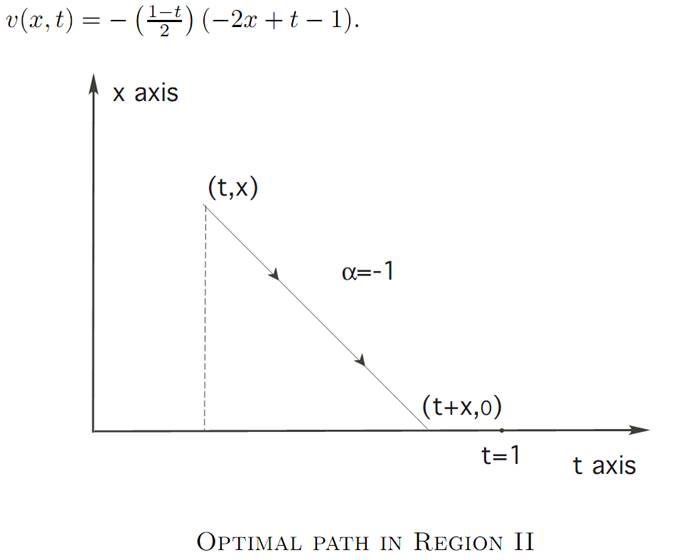

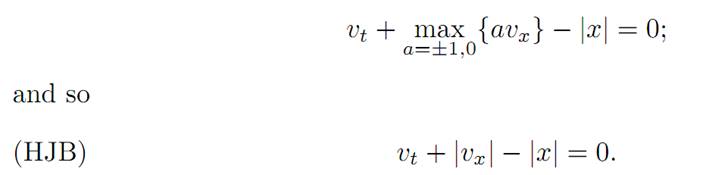

Checking the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman PDE. Now the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equation for our problem reads

(1.1)

(1.1)

for f = a, r = −|x|. We rewrite this as

We must check that the value function v, defined explicitly above in Regions I-III,

does in fact solve this PDE, with the terminal condition that v(x, 1) = g(x) = 0.

Now in Region II v = −x2/2 , vt = 0, vx = −x. Hence

vt + |vx| − |x| = 0 + | − x| − |x| = 0 in Region II,

in accordance with (HJB).

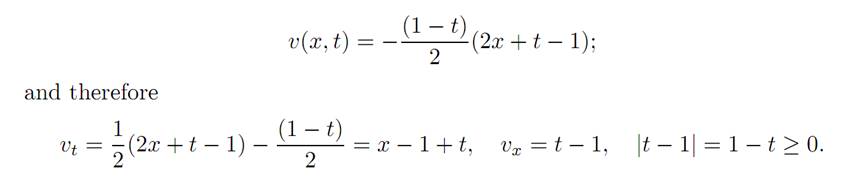

In Region III we have

Hence

vt + |vx| − |x| = x − 1 + t + |t − 1| − |x| = 0 in Region III,

because x > 0 there.

Likewise the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman PDE holds in Region I.

REMARKS. (i) In the example, v is not continuously differentiable on the borderlines between Regions II and I or III.

(ii) In general, it may not be possible actually to find the optimal feedback control. For example, reconsider the above problem, but now with A = {−1, 1}.

We still have α = sgn(vx), but there is no optimal control in Region II.

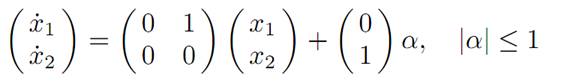

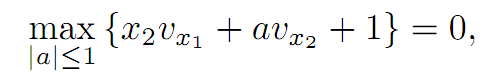

1.2 EXAMPLE 2: ROCKET RAILROAD CAR. Recall that the equations of motion in this model are

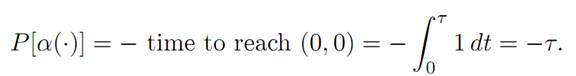

and

To use the method of dynamic programming, we define v(x1, x2) to be minus the least time it takes to get to the origin (0, 0), given we start at the point (x1, x2).

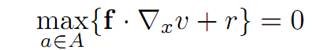

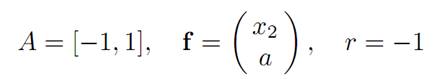

What is the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equation? Note v does not depend on t, and so we have

For

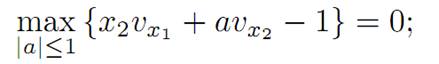

Hence our PDE reads

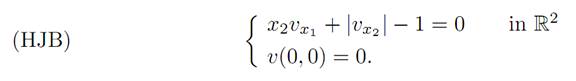

and consequently

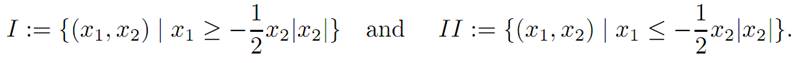

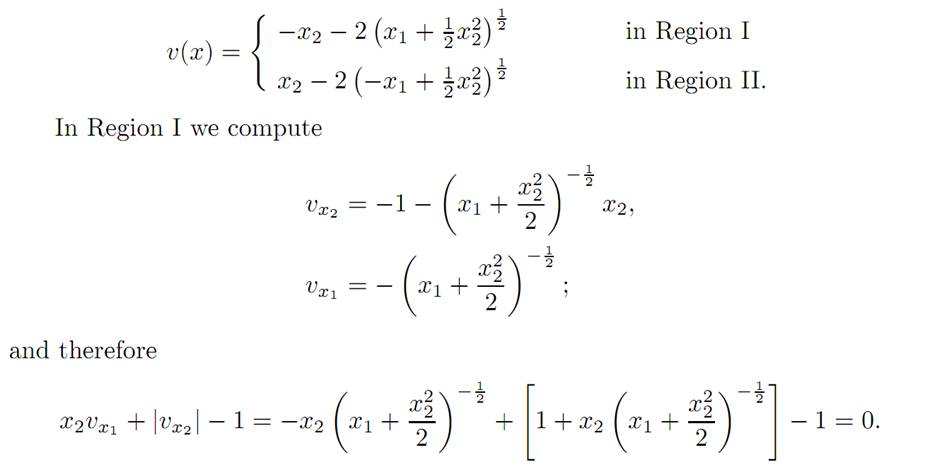

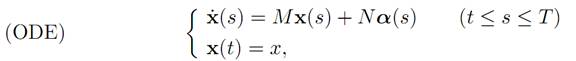

Checking the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman PDE. We now confirm that vreally satisfies (HJB). For this, define the regions

A direct computation, the details of which we omit, reveals that

This confirms that our (HJB) equation holds in Region I, and a similar calculation holds in Region II.

Optimal control. Since

the optimal control is

α = sgn vx2 .

1.3 EXAMPLE 3: GENERAL LINEAR-QUADRATIC REGULATOR

For this important problem, we are given matrices M,B,D ∈ Mn×n, N ∈ Mn×m, C ∈ Mm×m; and assume

B,C,D are symmetric

And

nonnegative definite, and C is invertible.

We take the linear dynamics

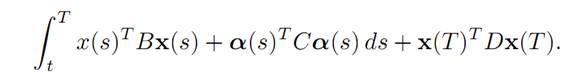

for which we want to minimize the quadratic cost functional

So we must maximize the payoff

The control values are unconstrained, meaning that the control parameter values can range over all of A = Rm.

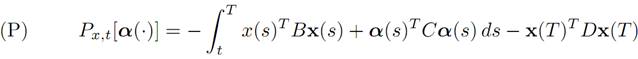

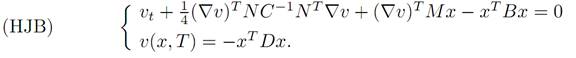

We will solve by dynamic programming the problem of designing an optimal control. To carry out this plan, we first compute the Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman equation

We also have the terminal condition

v(x, T) = −xTDx

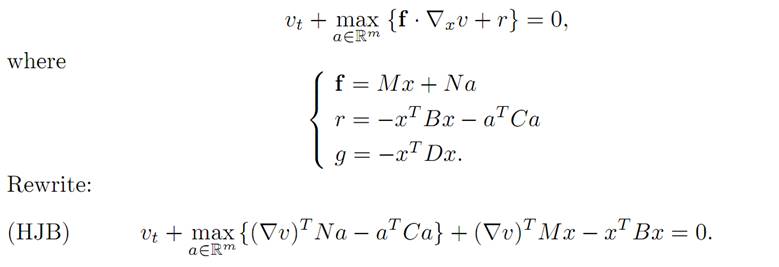

Minimization. For what value of the control parameter a is the minimum attained? To understand this, we define Q(a) := (∇v)TNa−aTCa, and determine where Q has a minimum by computing the partial derivatives Qaj for j = 1, . . . ,m and setting them equal to 0. This gives the identitites

This is the formula for the optimal feedback control: It will be very useful once we compute the value function v.

Finding the value function. We insert our formula a = 1/2C−1NT∇v into(HJB), and this PDE then reads

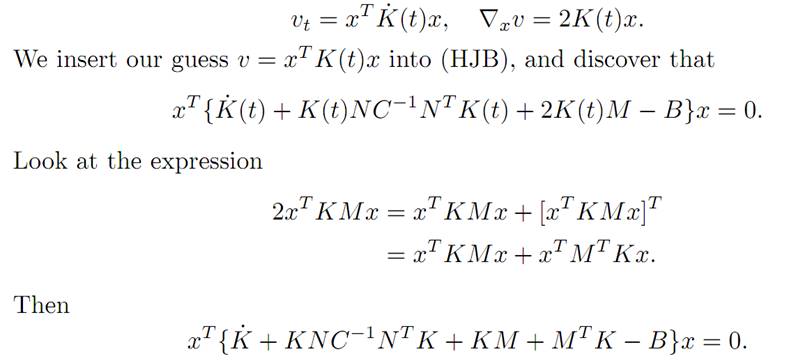

Our next move is to guess the form of the solution, namely

v(x, t) = xTK(t)x,

provided the symmetric n×n-matrix valued function K(.) is properly selected. Will this guess work?

Now, since −xTK(T)x = −v(x, T) = xTDx, we must have the terminal condition that

K(T) = −D.

Next, compute that

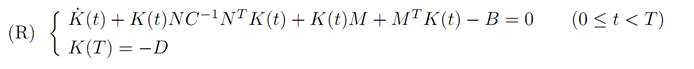

This identity will hold if K(.) satisfies the matrix Riccati equation

In summary, if we can solve the Riccati equation (R), we can construct an optimal feedback control

α∗(t) = C−1NTK(t)x(t)

Furthermore, (R) in fact does have a solution, as explained for instance in the book of Fleming-Rishel [F-R].

References

[B-CD] M. Bardi and I. Capuzzo-Dolcetta, Optimal Control and Viscosity Solutions of Hamilton-Jacobi-Bellman Equations, Birkhauser, 1997.

[B-J] N. Barron and R. Jensen, The Pontryagin maximum principle from dynamic programming and viscosity solutions to first-order partial differential equations, Transactions AMS 298 (1986), 635–641.

[C1] F. Clarke, Optimization and Nonsmooth Analysis, Wiley-Interscience, 1983.

[C2] F. Clarke, Methods of Dynamic and Nonsmooth Optimization, CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics, SIAM, 1989.

[Cr] B. D. Craven, Control and Optimization, Chapman & Hall, 1995.

[E] L. C. Evans, An Introduction to Stochastic Differential Equations, lecture notes avail-able at http://math.berkeley.edu/˜ evans/SDE.course.pdf.

[F-R] W. Fleming and R. Rishel, Deterministic and Stochastic Optimal Control, Springer, 1975.

[F-S] W. Fleming and M. Soner, Controlled Markov Processes and Viscosity Solutions, Springer, 1993.

[H] L. Hocking, Optimal Control: An Introduction to the Theory with Applications, OxfordUniversity Press, 1991.

[I] R. Isaacs, Differential Games: A mathematical theory with applications to warfare and pursuit, control and optimization, Wiley, 1965 (reprinted by Dover in 1999).

[K] G. Knowles, An Introduction to Applied Optimal Control, Academic Press, 1981.

[Kr] N. V. Krylov, Controlled Diffusion Processes, Springer, 1980.

[L-M] E. B. Lee and L. Markus, Foundations of Optimal Control Theory, Wiley, 1967.

[L] J. Lewin, Differential Games: Theory and methods for solving game problems with singular surfaces, Springer, 1994.

[M-S] J. Macki and A. Strauss, Introduction to Optimal Control Theory, Springer, 1982.

[O] B. K. Oksendal, Stochastic Differential Equations: An Introduction with Applications, 4th ed., Springer, 1995.

[O-W] G. Oster and E. O. Wilson, Caste and Ecology in Social Insects, Princeton UniversityPress.

[P-B-G-M] L. S. Pontryagin, V. G. Boltyanski, R. S. Gamkrelidze and E. F. Mishchenko, The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes, Interscience, 1962.

[T] William J. Terrell, Some fundamental control theory I: Controllability, observability, and duality, American Math Monthly 106 (1999), 705–719.

الاكثر قراءة في نظرية التحكم

الاكثر قراءة في نظرية التحكم

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة