تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

Imaginary numbers

المؤلف:

Tony Crilly

المصدر:

50 mathematical ideas you really need to know

الجزء والصفحة:

44-49

24-2-2016

2225

We can certainly imagine numbers. Sometimes I imagine my bank account is a million pounds in credit and there’s no question that would be an ‘imaginary number’. But the mathematical use of imaginary is nothing to do with this daydreaming.

The label ‘imaginary’ is thought to be due to the philosopher and mathematician René Descartes, in recognition of curious solutions of equations which were definitely not ordinary numbers. Do imaginary numbers exist or not? This was a question chewed over by philosophers as they focused on the word imaginary. For mathematicians the existence of imaginary numbers is not an issue. They are as much a part of everyday life as the number 5 or π. Imaginary numbers may not help with your shopping trips, but go and ask any aircraft designer or electrical engineer and you will find they are vitally important. And by adding a real number and an imaginary number together we obtain what’s called a ‘complex number’, which immediately sounds less philosophically troublesome. The theory of complex numbers turns on the square root of minus 1. So what number, when squared, gives −1?

If you take any non-zero number and multiply it by itself (square it) you always get a positive number. This is believable when squaring positive numbers but is it true if we square negative numbers? We can use −1 × −1 as a test case. Even if we have forgotten the school rule that ‘two negatives make a positive’ we may remember that the answer is either −1 or +1. If we thought −1 × −1 equalled −1 we could divide each side by −1 and end up with the conclusion that −1 = 1, which is nonsense. So we must conclude −1 × −1 = 1, which is positive. The same argument can be made for other negative numbers besides −1, and so, when any real number is squared the result can never be negative. This caused a sticking point in the early years of complex numbers in the 16th century. When this was overcome, the answer liberated mathematics from the shackles of ordinary numbers and opened up vast fields of inquiry undreamed of previously. The development of complex numbers is the ‘completion of the real numbers’ to a naturally more perfect system.

Engineering

Even engineers, a very practical breed, have found uses for complex numbers. When Michael Faraday discovered alternating current in the 1830s, imaginary numbers gained a physical reality. In this case the letter j is used to represent √–1 instead of i because i stands for electrical current.

The square root of –1

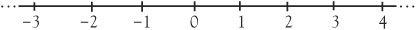

We have already seen that, restricted to the real number line,

there is no square root of −1 as the square of any number cannot be negative. If we continue to think of numbers only on the real number line, we might as well give up, continue to call them imaginary numbers, go for a cup of tea with the philosophers, and have nothing more to do with them. Or we could take the bold step of accepting √−1 as a new entity, which we denote by i.

By this single mental act, imaginary numbers do exist. What they are we do not know, but we believe in their existence. At least we know i2 = −1. So in our new system of numbers we have all our old friends like the real numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, π, e,  and

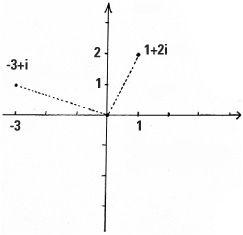

and  , with some new ones involving i such as 1 + 2i, −3 + i, 2 + 3i,

, with some new ones involving i such as 1 + 2i, −3 + i, 2 + 3i,  ,

,  , e + πi and so on.

, e + πi and so on.

This momentous step in mathematics was taken around the beginning of the 19th century, when we escaped from the one-dimensional number line into a strange new two-dimensional number plane.

Adding and multiplying

Now that we have complex numbers in our mind, numbers with the form a + bi, what can we do with them? Just like real numbers, they can be added and multiplied together. We add them by adding their respective parts. So 2 + 3i added to 8 + 4i gives (2 + 8) + (3 + 4)i with the result 10 + 7i.

Multiplication is almost as straightforward. If we want to multiply 2 + 3i by 8 + 4i we first multiply each pair of symbols together and add the resulting terms, 16, 8i, 24i and 12i2 (in this last term, we replace i2 by −1), together. The result of the multiplication is therefore (16 – 12) + (8i + 24i) which is the complex number 4 + 32i.

(2 + 3i) × (8 + 4i) = (2 × 8) + (2 × 4i) + (3i × 8) + (3i × 4i)

With complex numbers, all the ordinary rules of arithmetic are satisfied. Subtraction and division are always possible (except by the complex number 0 + 0i, but this was not allowed for zero in real numbers either). In fact the complex numbers enjoy all the properties of the real numbers save one. We cannot split them into positive ones and negative ones as we could with the real numbers.

The Argand diagram

The two-dimensionality of complex numbers is clearly seen by representing them on a diagram. The complex numbers −3 + i and 1 + 2i can be drawn on what we call an Argand diagram: This way of picturing complex numbers was named after Jean Robert Argand, a Swiss mathematician, though others had a similar notion at around the same time.

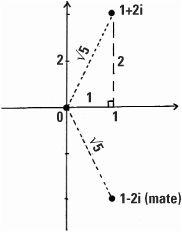

Every complex number has a ‘mate’ officially called its ‘conjugate’. The mate of 1 + 2i is 1 − 2i found by reversing the sign in front of the second component. The mate of 1 − 2i, by the same token, is 1 + 2i, so that is true mateship.

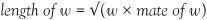

Adding and multiplying mates together always produces a real number. In the case of adding 1 + 2i and 1 −2i we get 2, and multiplying them we get 5. This multiplication is more interesting. The answer 5 is the square of the ‘length’ of the complex number 1 + 2i and this equals the length of its mate. Put the other way, we could define the length of a complex number as:

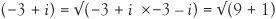

Checking this for −3 + i, we find that length of  and so the length of

and so the length of  .

.

The separation of the complex numbers from mysticism owes much to Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Ireland’s premier mathematician in the 19th century. He recognized that i wasn’t actually needed for the theory. It only acted as a placeholder and could be thrown away. Hamilton considered a complex number as an ‘ordered pair’ of real numbers (a, b), bringing out their two-dimensional quality and making no appeal to the mystical √−1. Shorn of i, addition becomes

(2, 3) + (8, 4) = (10, 7)

and, a little less obviously, multiplication is

(2, 3) × (8, 4) = (4, 32)

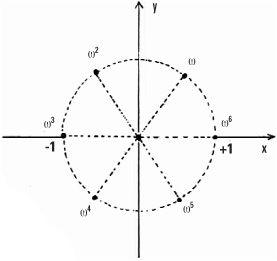

The completeness of the complex number system becomes clearer when we think of what are called ‘the nth roots of unity’ (for mathematicians ‘unity’ means ‘one’). These are the solutions of the equation zn = 1. Let’s take z6 = 1 as an example. There are the two roots z = 1 and z = −1 on the real number line (because 16 = 1 and (−1)6 = 1), but where are the others when surely there should be six? Like the two real roots, all of the six roots have unit length and are found on the circle centred at the origin and of unit radius.

More is true. If we look at w = ½+ √3/2 i which is the root in the first quadrant, the successive roots (moving in an anticlockwise direction) are w2, w3, w4, w5, w6 = 1 and lie at the vertices of a regular hexagon. In general the n roots of unity will each lie on the circle and be at the corners or ‘vertices’ of a regular n-sided shape or polygon.

Extending complex numbers

Once mathematicians had complex numbers they instinctively sought generalizations. Complex numbers are 2-dimensional, but what is special about 2? For years, Hamilton sought to construct 3-dimensional numbers and work out a way to add and multiply them but he was only successful when he switched to four dimensions. Soon afterwards these 4-dimensional numbers were themselves generalized to 8 dimensions (called Cayley numbers). Many wondered about 16-dimensional numbers as a possible continuation of the story – but 50 years after Hamilton’s momentous feat, they were proved impossible.

the condensed idea

Unreal numbers with real uses

الاكثر قراءة في هل تعلم

الاكثر قراءة في هل تعلم

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)