A hierarchy of semantic features

المؤلف:

THOMAS G. BEVER and PETER S. ROSENBAUM

المؤلف:

THOMAS G. BEVER and PETER S. ROSENBAUM

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

588-33

الجزء والصفحة:

588-33

2024-08-26

2024-08-26

1370

1370

A hierarchy of semantic features

For instance, the features in the matrix in (1) are specified with some redundancy. We can see from inspection of the frames in (2 a) and (2 b) that if a noun can act as ‘ + human’ then it can occur as ‘ + animate’ although the reverse is not necessarily true. For example, if we can say ‘the man thought it over’ we can also say ‘the man sensed the danger’, but if we can say ‘the ant ran away’ we cannot necessarily say ‘the ant answered slowly’.

Consequently, any word marked ‘-f human’ can be predicted as being ‘+animate’. This prediction is represented in rule (3 a), which obviates the necessity of lexical entries for ‘animateness’ in nouns which are marked as ‘human’.

(3) (a) + human ——> + animate

(b) + animate ——> - plant

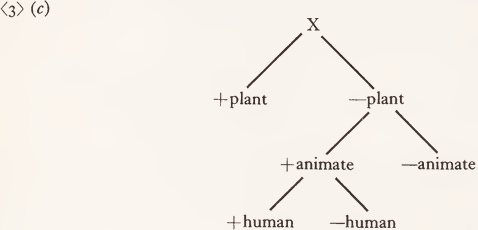

Similarly, it is predictable that if a noun is ‘+animate’ it is ‘ — plant’ in English, although the reverse is not true. Then, rule (3b) by allows the features ‘ — plant ’ to be left out of the lexical entry for ‘ant’. Such redundancy rules simply reflect a class- inclusion hierarchy among the semantic features (e.g. (3 c)).

The evaluation criterion requires the simplest acceptable solution to be used. Accordingly, the solution which includes the semantic redundancy rules in (3) is clearly indicated over a solution without these rules, given that the theory allows such rules at all. (Notice that rule (3b) is not universal but is a rule peculiar to English, since there are languages in which at least some plants can be considered animate.)

We can now ask if the predictions made by this analysis about new lexical items are valid or not. Consider the two potential English words, ‘og ’ and ‘triffid ’, on the right hand side of figure (1). ‘og ’ is intended to be a word which signifies the dead remains of an entire plant, in the way which ‘ carcass ’ indicates the dead remains of an entire animal. ‘triffid ’, on the other hand, indicates a kind of pine tree that moves and communicates.

Neither of these words exists in everyday English, and they may both be classified as semantic lexical gaps - that is, they are combinations of semantic features which are not combined within a single lexical entry in English. Yet the reasons for their non-occurrence are radically different according to the analysis in (3). Rule (3b) by in principle blocks the appearance of any word like ‘ triffid ’ which is both plant and animal, but the word ‘ og ’ is not blocked by anything in the lexical rules. That is, ‘triffid’ is classified by our analysis as a systematic gap, while the non-occurrence of ‘ og ’ is entirely accidental.

This distinction, made as an incidental part of our analysis, appears to be sup¬ ported by the intuitions of speakers of English. Nobody would be surprised to learn that professional loggers and foresters have some word in their vocabulary which indicates the whole of a dead tree. But everybody would be surprised to learn that foresters have a single word for trees which they think are animals. [It is that sense of surprise for English speakers which made possible The Day of the Triffids, a science-fiction novel in which the discovery of this concept is a primary vehicle for the plot.]

This result represents an independent corroboration of the general form of the semantic lexicon and the evaluation criteria which we proposed above. The rules in (3 a, b) were not introduced to block systematic lexical gaps, but to achieve the highest valued semantic analysis. The fact that the systematic gaps they predict correspond to the intuitive ones is a distinct empirical corroboration of the precise formal characteristics of this form of semantic theory.

We have shown that an explanatory lexical semantic theory is possible, and have indicated some of its characteristics and empirical validations. We briefly indicate some other semantic lexical devices, the lexical distinctions which they predict, and the validity of those predictions.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة