Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

MEMORY AND RECOGNITION

المؤلف:

ERIC H. LENNEBERG

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

547-30

2024-08-25

1124

MEMORY AND RECOGNITION

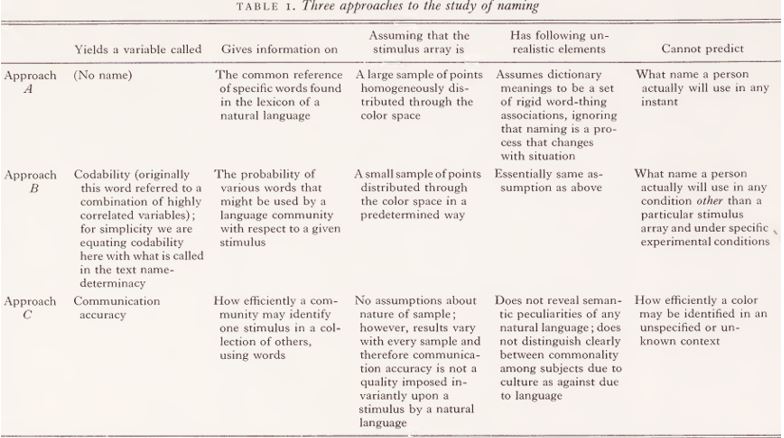

The first experiment on the effects of certain language habits on memory and recognition was carried out by Brown and Lenneberg (1954). Until that time investigators had attempted to manipulate language variables by quite ephemeral conditions such as teaching subjects nonsense names for nonsense objects or influencing their verbal habits by instructions given immediately prior to the cognitive task (Carmichael, Hogan and Walter, 1932; Kurtz and Hovland, 1953; and others cited in Carroll, 1964), but the semantic structure of the subjects’ native language was neither known to the experimenter nor utilized as a variable in the experiment. Yet the habits induced by one’s native language have acted upon an individual all his life and are, therefore, much more relevant to the basic problem that concerns us here than the verbal habits that can be established during a single experimental session. Thus, experiments that build upon the properties of a natural language are in a sense more crucial than the other type.

The Brown and Lenneberg experiment need not be reported here in any great detail. Subjects were screened for color-blindness and had to be native born American-English speakers. Their task consisted of correctly recognizing certain colors. They were shown one color (or in some experimental conditions four colors) at a time for a short period; these were the stimulus colors.

After a timed interval they viewed a large color chart (to which we shall refer as the color context) from which they chose the colors they had been shown before. The colors were identified by pointing so that no descriptive words were used either by the experimenter or the subject.

In earlier investigations the foci and borders of English name maps had been determined through Approach A; basing ourselves on this information we selected a small sample of colors (the stimulus colors) consisting of all foci and an example of each border. A few additional colors were added (only the region of high saturation was included). This yielded a sample of 24 colors. Next we used Approach B in order to obtain lists of words and descriptive phrases actually used by English speakers in order to refer to the colors in our particular sample and context. Approaches A and B together provided us with background knowledge of the language habits that English-speaking subjects might bring to bear upon the task of color recognition in our experiment. We hypothesized that there would be a relationship between the two.

The measure of name-determinacy, obtained through Approach B, was found to be highly correlated with response latency and shortness of response (as confirmed by Beare, 1963) and was called by Brown and Lenneberg codability. Codability is essentially a measure of how well people agree in giving a name to a stimulus, in our case a color. Good agreement (that is, high codability) may be due to two independent factors: the language of the speakers may provide, through its vocabulary, a highly characteristic, unique, and unambiguous word for a highly specific stimulus (for example, the physical color of blood); or the stimulus may in fact be quite non-descript in the language, but it is given special salience in a physical context (for instance red hair). Codability does not distinguish these two factors.

We found that codability of a color did not predict its recognizability when the recognition task was easy (one color to be identified after a seven second waiting period); however, as the task was made more difficult codability began to correlate with recognizability and the relationship was most clearly seen in the most difficult of the tasks (four colors had to be recognized after a three minute waiting period during which subjects were given irrelevant tasks to perform).

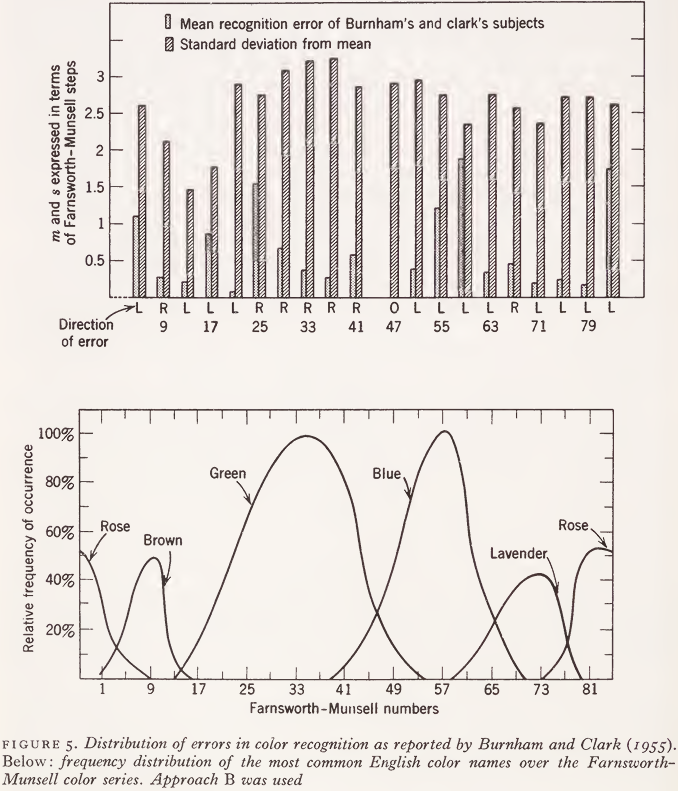

At first these results looked like experimental proof that under certain conditions a person’s native language may facilitate or handicap a memory-function. However, it became apparent later that the role of physical context needed to be studied further (see also Krauss and Weinheimer, 1965). Burnham and Clark (1955) conducted a color recognition experiment employing essentially the same procedure as Brown and Lenneberg but using a different sample of colors (namely the Farnsworth- Munsell Test Colors instead of the high saturation colors from the Munsell Book of Colors). They found that colors differed in their recognizability as shown in Fig. 5 with mistakes occurring in specific directions, clearly pointing to some systematic bias in the subjects’ performance. Lenneberg (1957) obtained naming data on the same stimulus material and a comparison of these data with those of Burnham and Clark (Fig. 3) seemed to show that the bias may be related to the semantic structure ‘ built into ’ the subjects by virtue of their native English. The only difficulty with this interpretation is this. In the Brown and Lenneberg experiment a positive correlation was found between codability and recognizability, whereas the recognizability of the Burnham and Clark colors was negatively correlated with their codability. This divergence is not due to experimental artifact. Lantz (unpublished data) repeated the Burnham and Clark experiment twice with different groups of adults in different parts of the country and Lantz and Stefflre (1964) replicated the Brown and Lenneberg experiment, all with similar results.

There are strong reasons to attribute the difference in outcome of the two experiments to the peculiarities of the stimulus arrays and the physical context of the individual colors.

Burnham and Clark had hoped to eliminate endpoints by using a circular stimulus array. But Ss’ naming habits restructured the material so as to furnish certain anchoring points: namely, the boundaries between name maps. Thus, a few colors acquired a distinctive feature, whereas most of the colors, all that fell within a name region, tended to be assimilated in memory. To remember the word ‘green’ in this task was of no help since there were so many greens; but to remember that the color was on the border of ‘green’ and ‘not-green’ enabled the subject to localize the stimulus color with great accuracy in the color context.

The Brown and Lenneberg study did not provide subjects with any two or three outstanding landmarks for recognition. Since there was no more than one color within individual name categories, the possibility of assimilating colors (or of grouping colors into classes of stimulus equivalence) was drastically reduced if not eliminated. On the other hand, so many colors marked boundaries, that betwixtness as such was no longer a distinctive feature.

These two experiments suggest that semantic structure influences recognition only under certain experimental circumstances, namely when the task is difficult and the stimuli are chosen in a certain way. If it is possible to obtain a positive as well as a negative correlation between codability and recognizability, it will also be possible to select stimuli in such a way that codability has zero correlation with recognizability of a color. In other words, both the Brown and Lenneberg experiment and the Burn¬ ham and Clark experiment are special cases.

Lantz and Stefflre (1964) have shown that it is actually not the semantic characteristics of the vocabulary of a natural language that determine the cognitive process recognition but the peculiar use subjects will make of language in a particular situation. Instead of using the information from either Approach A or B (which primarily brings out language peculiarities), they used Approach C which measures the accuracy of communication in a specific setting, without evaluating the words that subjects choose to use; their independent variable was communication accuracy which reflects efficiency of the process but does not specify by what means it is done. This is quite proper in that the how is largely left to the creativity of the individual; he is, in fact, not bound by the semantics of his natural language; there is little evidence of the tyrannical grip of words on cognition.

When communication accuracy is determined for every color in a specific stimulus array it predicts recognition of that color quite well as may be seen from Fig. 6. Codability, on the other hand, predicts recognizability only in special contexts and stimulus arrays. From this we may infer that subjects make use of the ready-made reference facilities offered them through their vocabulary, only under certain circumstances. The rigid or standard use of these words, without creative qualifications, is in many circumstances not conducive to efficient communication. Communication accuracy or efficiency will depend frequently on individual ingenuity rather than on the language spoken by the communicator.

The Lantz and Stefflre experiment points to an interesting circumstance. The variable, communication accuracy, is a distinctly social phenomenon. But recognition of colors is an entirely intrapersonal process. Lantz and Stefflre suggest that there are situations in which the individual communicates with himself over time.

This is a fruitful way of looking at the experimental results and one that also has important implications regarding human communication in more general terms. It stresses, once again, the probability that human communication is made possible by the identity of cognitive processing within each individual. The social aspect of communication seems to reflect an internal cognitive process. We are tempted to ask now, ‘What is prior - the social or the internal process? ’ At present, there is no clear answer to this, but the cognitive functioning of congenitally deaf children, before they have learned to read, write, or lip-read (in short, before they have language) appears to be, by and large, similar enough to their hearing contemporaries to lead me to believe that the internal process is the condition for the social process, although certain influences of the social environment upon intrapersonal cognitive development cannot be denied.

What preliminary conclusions may we draw then from these empirical investigations? Four major facts emerge. First, the semantic structure of a given language only has a mildly biasing effect upon recognition under special circumstances; limitations of vocabulary may be largely overcome by the creative use of descriptive words. Second, a study of the efficiency of communication in a social setting (of healthy individuals) may give clues to intrapersonal processes. Third, efficiency of communication is mostly dependent upon such extra-semantic factors as the number of and perceptual distance between discriminanda. Fourth, the social communication measures become more predictive of the intrapersonal processes as the difficulty of the individual’s task increases either by taxing memory or by reduction of cues (cf. also Frijda and Van de Geer, 1961; Van de Geer, i960; Glanzer and Clark, 1962; Krauss and Weinheimer, 1965).

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)