Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Parasitic arguments

المؤلف:

MANFRED BIERWISCH

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

428-24

2024-08-17

1282

Parasitic arguments

We have discussed so far predicative features whose arguments are provided essentially by NPs bearing the relevant syntactic relation to the constituent containing the features in question. I will now consider some phenomena which seem to require a different sort of argument, inducing thereby a further classification of semantic features. The need for such subsidiary arguments can be illustrated by means of the so-called relative adjectives such as ‘heavy’, ‘old’, ‘loud’, ‘big’, ‘ long ’, ‘ high ’, and their antonyms.

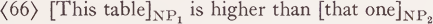

Relative adjectives specify a certain parameter and indicate that the object(s) referred to exceed (or fall short of) a certain point within that parameter. This point can be indicated explicitly in comparative constructions such as (60), it is understood implicitly in cases like (61) and must hence be part of their readings too:

(60) John has a bigger house than Bill (has).

(61) John has a big house.

Analyzing a set of German adjectives describing spatial dimensions, which are a proper subset of relative adjectives, I tried to account for the facts just mentioned by means of simple markers such as (Vertical), (Maximal), (Secondary), etc. specifying the relevant parameters, and the pair of markers ( + Pol) and ( — Pol) to indicate the extension with respect to the specified parameter. (For details see Bierwisch, 1967.) This analysis is unsatisfactory for at least two reasons. Firstly, it does not represent correctly the connections between the different features occurring in a reading (cf. note a, p.411, above). Secondly, it cannot capture certain important empirical facts. Consider the following examples:

(62)(a) Towers are high.

(b) Towers are high for buildings.

(c) Towers are higher than average buildings.

(63)(a) These towers are high.

(b) These towers are high for towers.

(c) These towers are higher than average towers.

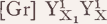

The sentences in (62) and again in (63) are certainly close paraphrases. This shows that even the positive form of relational adjectives must have a reading similar to that of the comparative, the term for comparison being provided by the average elements of a certain class. This class is that of the subject NP if it is not generic, it is the next larger class, i.e. the genus proximum, if the NP is generic.1 What is important here is that we need a relational feature representing the comparison involved in relative adjectives. Thus we will replace the elements (+ Pol) and (— Pol) by the relation ‘ Greater than ’ and its converse, represented as 1 [Gr] YZ ’ and ‘ [Gr-1] YZ’, respectively. But what is represented by the arguments Y and Z? Obviously, Y refers to the extent to which an object Xi occupies a certain parameter which is specified by the rest of the adjective’s reading. In other words, Y represents, in the present example, a certain spatial extension of the objects referred to by Xi. The second argument of ‘Gr’, then, indicates the corresponding extension of the compared objects. Thus the arguments of ‘ Gr ’ are of a rather different type than the Xi considered so far. In fact, they represent not objects, but properties of objects, where these properties are treated as a kind of parasitic or subsidiary argument.

They must be established by a further type of relational features extracting extensions (or other parameters) from the primary arguments. ' [Vert] Xi Y ’ with the interpretation ‘Y is the vertical extension of Xi’ and ‘[Max] XiY’ with the interpretation ‘ Y is the maximal extension of Xi’, for example, may specify the relevant parameters of ‘ high ’ and ‘ long respectively.2

The argument Y in these examples represents stretches. In other cases, e.g. in one reading of ‘ big ’, we need global extensions, i.e. something like the product of all relevant extensions. These might be introduced by a feature ‘ [Vol] XiY’.

Since the extensions introduced so far are constituted by the corresponding dimensionality of the primary objects, they must occur not only in the adjectives which assign to them a certain value (greater than a certain average, e.g.), but also in the reading of nouns which specify the dimensionality of the objects referred to. Thus the fact that ‘ line ’, ‘ square ’, and ‘ house ’ designate conceptually one, two, and three dimensional objects, respectively, might be expressed by the features ‘[1 Ext] Xi Y1’, ‘[2 Ext] Xi Y1, Y2’, and ‘ [3 Ext] Xi Y1 Y2 Y3’.3 Features of this type are part of the explication of the hitherto used global marker (Physical Object). They provide the arguments which must be substituted for the corresponding variables within the readings of relative adjectives.

Given the conventions discussed so far, the reading of ‘ high ’ can be given provisionally as (64):

(64) [Vert] XS Yi. [Gr] Yi Z

Z is still used as an unexplicated abbreviation for the vertical extension of the compared average object. (In comparative constructions it must be substituted by the representation of the concerned extension of the compared NP.) Yi a variable that is to be substituted by an extension of the reading of the subject-NP that does not contradict the condition ‘Vert’. We thus get (65) as the reading of ‘The table1 is high’, if we abbreviate all the features of ‘table’ not relevant here by ‘Table’:

Notice that the parasitic arguments that we have introduced represent sets of extensions (or other parameters), just as the primary arguments represent sets of objects: a sentence as ‘These tables are high’ says something about the set of vertical extensions of the set of objects involved.4

We must still go one step further in specifying the subsidiary arguments. According to our previous assumptions, the ‘ normal height ’ Z in the reading of ‘ high ’ must be replaced by the vertical extension of NP2 in a sentence like (66):

Hence the reading of (66) would contain a component ‘ [Gr] Y1 Y1’ But this is obviously wrong. What we need is an indexing of the subsidiary arguments with respect to the primary arguments whose parameters they represent. Instead of the Yi we must have something like  where the subscripts must be substituted by the same Xi which replaces the primary argument variable XS. This then would yield the correct component ‘

where the subscripts must be substituted by the same Xi which replaces the primary argument variable XS. This then would yield the correct component ‘  ’ instead of the rejected ‘ [Gr] Y1 Y1’ in the reading of (66).

’ instead of the rejected ‘ [Gr] Y1 Y1’ in the reading of (66).

A moment’s reflection shows that this double indexing is in a sense redundant, since it simply repeats information already expressed by the relational features ‘Vert’, ‘Max’, etc., which specify extensions of particular objects, not arbitrary ones. Our notation thus obscures somehow the relevant facts. We may remedy this deficiency by adapting another notion developed in modern logic, viz. that of relational descriptions.

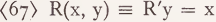

Given a two-place predicate ‘ R(x, y) ’ whose first argument is always uniquely specified if the second argument is given, an individual can be identified as the one which bears R to a given y. A relational description of this type is usually written as ‘ R'y ’. The element R' introduced here can be understood as a function mapping every y on a particular x, roughly speaking. Hence the following equivalence holds:

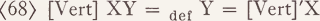

R'y is an individual of the same type as x, more precisely, it is a name of x. Notice now, that the features ‘Vert’, ‘Max’, and several others have precisely the property discussed here, except that it is the second argument which uniquely depends on the first, not vice versa. But this is only a notational arbitrariness. Based on the feature ‘ Vert ’ we may thus introduce a corresponding function by the following definition:

Similar functions can be derived from ‘Max’, ‘Vol’, etc. From (68) it follows that an expression of the form ‘[Vert]'X1’ is the name of the same set of extensions formerly represented as a variable with double index. Hence ‘ [Vert]'Xi’ has the status of an argument and must enter readings in precisely this role. If we assume that XN represents the above mentioned average object with respect to which the modified noun is compared, the reading of ‘ high ’ can now be given as follows:

Functions of the type discussed can also be derived from combinations of relational features. Thus ‘ [Vert.Max] Xi Y’ would say that Y is an extension of Xi which is both vertical and maximal. Hence ‘ [Vert.Max],Xi’ designates this extension. Combinations of this type are required for several adjectives. I cannot go into these details here.

What has been said with respect to relative adjectives, in particular to those referring to spatial extensions, applies to other parameters as well. A case of particular interest is time. The relation ‘ R ’ that was introduced provisionally to express the time-placement of a fact described by a proposition relates a fact to a time interval just as ‘ Vert ’ relates an object to its vertical extension. The variables representing time intervals are thus subsidiary arguments of the same kind as the variables over space intervals. Time designations such as ‘morning’, ‘hour’, ‘year’, etc. are then nouns where these subsidiary variables are turned into primary ones-just as in nominalized adjectives like ‘length’, ‘height’, ‘width’, etc. Problems of this type, however, are topics of separate investigations.

1 This differentiation between generic and nongeneric sentences with respect to the class used for comparison is obviously necessary, and raises a problem that cannot be dealt with by means of the relative semantic marker proposed by Katz (1967) in this connection. According to Katz’ analysis the comparison is made always with respect to the lowest category in the subject’s reading, i.e. its genus proximum. But the differentiation introduced above is still an oversimplification in several respects. Thus the sentence

(i) The high towers of the town will be reconstructed

is ambiguous, according to the restrictive or non-restrictive interpretation of the adjective ‘ high ’:

(ii) The towers of the town which are high will be reconstructed.

(iii) The towers of the town, which are high, will be reconstructed.

And these imply different norms for comparison, as can be seen from these paraphrases:

(iv) The towers of the town which are higher than the average towers of the town will be reconstructed.

(v) The towers of the town, which are higher than average towers, will be reconstructed.

In other words: restrictive modifiers behave like non-generic sentences, non-restrictive modifiers like generic ones with respect to the choice of the class for comparison. These and several other problems connected with the correct determination of the class to which the subject is compared deserve a careful analysis of both syntactic and semantic conditions which go far beyond the present aims. In the following discussion, I will simply presume that the class is somehow determined.

2 This is, of course, an oversimplification. Certain additional qualifications are required. The situation is still more complicated in other cases, such as ‘ wide ’, ‘ broad ’, ‘ deep ’, etc. My present purpose, however, is not a detailed analysis of the adjectives in question, but a discussion of certain formal aspects of their readings. For the details ignored here see Bierwisch (1967) and Teller (1969).

3 We thus have a set of features of the general form ‘ [n Ext] XiY1. . . Yn’ which would replace the element (n Space) used in Bierwisch (1967). Notice that ‘n Ext’ would be an exception to the above speculation that at most two-place features are necessary to account for the semantic structure of natural languages. This would force us to restrict the tentative claim to primary arguments. Another possibility would be to split up the n+1-place predicate 'n Ext’ into n two-place features ‘ [1 Ext] XiY1,. . ., ‘ [n Ext] XiYn’ where the direction of Yj is orthogonal to Yk for 1 ≤ k ≤ j —1. ‘1 Ext’ in turn might be replaced by ‘Vert’, in cases where the noun in question has a designated vertical axis. Similarly for ‘Max’, etc. In this case ‘j Ext’ would be the indication of an extension without any further specification. All these are details of an adequate axiomatization of the conceptual structure according to which spatial objects are organized by human perception. I am not concerned here with substantive questions of this kind.

4 This can be seen more clearly in nominalizations such as ‘the height of these tables’ where the parasitic arguments are turned into primary ones in a way not to be discussed here.

‘ The height’ in this case clearly refers to a set of extensions, not to a single one, as can be seen from examples like ‘The height of the tables is different’. In spite of the fact that a set containing more than one object is referred to, it is treated morphologically as singular.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)