Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Eliciting and testing techniques

المؤلف:

EDWARD H. BENDIX

المصدر:

Semantics AN INTERDISCIPLINARY READER IN PHILOSOPHY, LINGUISTICS AND PSYCHOLOGY

الجزء والصفحة:

397-23

2024-08-15

1286

Eliciting and testing techniques

There are a number of types of eliciting techniques and tests that can be used in generating the data on which to base a semantic account.1 These tests assume that the investigator has already obtained rough glosses, translations, and the like for forms in a language and is now interested in locating semantically similar forms more exactly within a paradigm of oppositions. It is also expected that possibilities of collocation with other forms are used as evidence, as well as possible referent situations. The basic goal in all the testing is to isolate and verify the semantic components that mark the oppositions in the paradigm.

The simplest type of technique, an open-ended interpretation test replicates the paradigm of oppositions by asking the informant to contrast P and Q, e.g. ‘What is the difference in meaning between He gave it to me and He lent it to me? ’ Applied to A has B and A gets B, such a test might lead to a first approximation of a definition A gets B — ‘A comes to have B ’ or, using the component labels given above, ‘ (B is an-Rh A) comes to be Such test sentences are constructed as minimal pairs varying only in the supposedly single lexemes tested. Differences in meaning are then assumed to be attributable only to the lexemes. In theory, however, the informant is free to imagine different background situations for the two sentences, in which case they would cease to be completely minimal pairs. To control for this, not-P and Q can be placed in the same sentence, thus replicating paradigmatic opposition with syntagmatic contrast. He could then be asked, ‘What does this mean? ’ or ‘ If you heard a person say this, what would you think he meant? ’ Such an interpretation test would have sentences as He didn't give it to me, he lent it to me or He didn't take it, he got it.

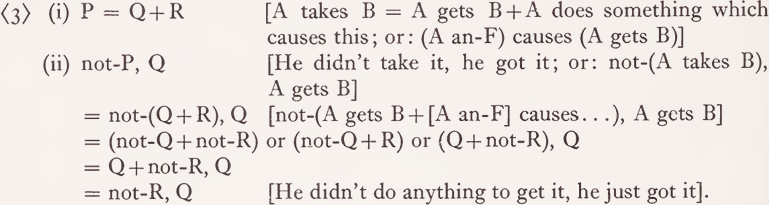

Assuming, for this last sentence, the informant interpretation ‘He didn’t do anything to get it, he just got it’, we could account for this response by formulating the component ‘ cause ’ in the following model of the informant’s process of interpretation:

The principle is to establish consistency between the first and second clauses. He didn't take it (‘not-P’) is ambiguous for negation of the components ‘Q’, ‘R’, or both, but only ‘Q + not-R’ is consistent with he got it (‘Q’). In this way the component ‘cause’ (‘R’) is isolated in the meaning of take. For economy and other reasons the definition could be reduced as A takes B = ‘(A an-F) causes (B is an-Rh A)’ but would have to be further revised if reason is found to consider A takes B a truncated form of the lexeme A takes B from C.

The test frame not-P, Q seems to be interpretable when of ‘ P ’ and ‘ Q ’, one is included in the other or when the unshared components are values along the same dimension. Otherwise (e.g., He didn’t keep it, he got it), not-P, Q seems quite difficult to interpret as anything but a denial of a previous statement P, which is always a possible interpretation in this test. On still other possibilities of informant interpretation than the strict account given above.

Such interpretation tests are fairly open-ended and more exploratory and offer the investigator a range of responses from which to induce the possible identity of components. He may then go on to test hypothesized components with more rigorous multiple-choice tests of the types described next.

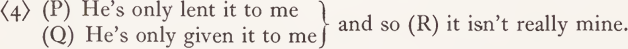

In a type of matching test, two minimal-pair sentences, P and Q, are contrasted for greater similarity in meaning to a third sentence R which expresses a presumed component of the meaning of P. In one form, this type involves a syllogistic argument. For example, for ‘B is not A’s’ (‘R’) as a component of the meaning of C lends B to A (P):

This might also take the form Since P/Since Q: R. In the syllogism, R is the proper conclusion if P is the minor premise. The major premise is covert and is the state¬ ment of equivalence which defines P = ‘. . . + R’. 2

This type may also take the form of a ranking test in which an informant is asked which of two sentences makes more sense or is easier to interpret. For example:

(5) (i) Since (P) he’s only lent it to me, (R) it isn’t really mine

Since (Q) he’s only given it to me, (R) it isn’t really mine

(ii) Since (P) he’s only lent it to me, (R) it isn’t really mine

Since (P) he’s only lent it to me, (not-R) it’s really mine

or for ‘A has B, (immediately) before T’ as a component of A keeps B, at T:

(6) If he has it, he’ll keep it

If he doesn’t have it, he’ll keep it.

Informants, thus, are not asked to make absolute judgments that characterize certain sentences as meaningless, senseless, inconsistent, impossible to interpret, etc., but rather to rank sentences as more or less meaningful, easy to interpret, etc. Enough has already been said about the interpretability of ‘ meaningless ’ sentences. If he doesn't have it, he'll keep it makes sense, for example, if one supplies the background context that ‘ he ’ is a stamp collector about to be given a copy of a stamp of which he may or may not already have another copy: ‘ If he has it, he’ll trade it for a stamp he doesn’t have; if he doesn’t have it, he’ll keep it.’ The greater number of operations necessary to make a sentence interpretable is what makes it rank lower.

An important type of ranking test aims at separating criterial semantic components of an item (Weinreich 1962: 33), i.e. those that are necessarily implied by it, from elements of meaning not criterial to it. Again, the only semantic elements tested would be such as had already become likely candidates for being components as the result of interpretation tests and similar sources. Let us assume that the test sentence She didn't give it to him, she lent it to him has given rise to the candidates ‘ she said that he couldn’t keep it as long as he wished ’ and ‘ she said it wouldn’t be his’ as components of she lent it to him. Compare the following pairs of sentences:

(7) (i) (a) She lent it to him but said he could keep it as long as he wished

(b) She lent it to him but said he couldn’t keep it as long as he wished

(ii) (a) She lent it to him but said it would be his

(b) She lent it to him but said it wouldn’t be his.

In (7i), (a) seems clearly to rank higher than (b); in (7 ii) a clear ranking does not seem so easy. Another format does not use but:

(8) (a) They lent him a book that wasn’t his

(b) They lent him a book that was his.

However, we will restrict ourselves to an account of the but-test (Weinreich 1963: 154. n- 4)-

In the ordinary usage of P but R, the but-clause negates an element not criterial to P. This may be a semantic feature more closely associated as a connotation of P or, more broadly, a previous expectation, assertion, etc.:

(9) (i) Given: (a) P but R [e.g., He’s lost his watch but knows where it is]

(b) P but not-R [e.g., He’s lost his watch but doesn’t know where it is]

(ii) If R negates an element not criterial to P, informants should rank (a) higher; if not-R does, they should choose (b)

(iii) If, of R and not-R, one is a criterial component of P and, thus, the other negates this component, we expect informants to consider both (a) and (b) odd, difficult to interpret, needing rephrasing, etc.

In the case of (9 iii), other means, such as interpretation tests, would make clear whether R or not-R is a component of P. In constructing but-test sentences, a degree of simplicity is maintained by not having not-P as the first clause, for the wide scope of this negation would leave indeterminate which component of P is being negated by the informant. This fact should become clearer from the following exposition of the but-test.

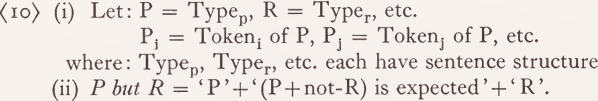

In the ordinary usage of P but R, the noncriterial element is not-R. For example, HRs lost his watch but knows where it is, where not-R would be He doesn't know where it is. The criterial components may be represented as Q. Where not-R is a connotation of P, this may be represented as P = Q(not-R), with the following definition :

(11) [P = Q(not-R)] = [(Pi = Q +not-R) and (Pj = Q)].

P = Q(not-R) must therefore be read “ If someone asserts ‘ P ’, he is either asserting ‘Q + not-R’, or he is asserting ‘Q’”, and not “If someone asserts ‘P’, he is asserting ‘Q + not-R or Q'."3 In this case, then,

(12) P but R = Q(not-R) + [(Q + not-R) is expected]+ R

so that a speaker may use P but R to express Q + R.

Next there is one test case where Q and not-R are both criterial: P = Q + not-R. This would give

(13) [P but R] = [P+...+R] = [Q + not-R + . . . + R]

which is a contradiction, as in He's lost his watch but did so intentionally, where not intentionally (not-R) is criterial for lose (P).4 Hearing such an utterance in isolation, a person might follow up his initial reaction that it is self-contradictory in one or more of the following ways, among others:

(a) He may reject it on the grounds that the speaker is violating the code or talking nonsense: e.g. ‘ It makes no sense ’ or ‘ It makes no sense to say that someone loses something intentionally.’

(b) He may interpret it as denying a previous assertion ‘not-R’ or ‘P +not-R’: ‘ Someone must have said it wasn’t intentional.’

(c) He may suspect a variant version of the code, namely that for the speaker ‘P = Q(not-R)’: ‘. . .must think that losing something can refer to an intentional act as well.’

(d) He may interpret the contradiction as expressing irony and resolve it by replacing ‘ P ’ with ‘ Q ’, which gives ‘ Q + . . . + R [and thus not-P] ‘.5 He may then interpret the irony as ‘ Someone falsely thinks or says P ’ and paraphrase P but R: ‘ He’s lost his watch, so he says (or so you think), but actually he got rid of it ’, ‘ He’s lost his watch, so he thinks, but unconsciously he actually got rid of it ’, etc.

(e) He may suspect a lapse on the part of the speaker and reject ‘not-R’ and thereby ‘ P ’: ‘ Since he did so intentionally, he didn’t really lose it or it wasn’t really a case of losing.’

Finally there is another test case where, still, P=Q + not-R, but this time the utterance is P but not-R, as in He's lost his watch but didn't do so intentionally:

(14) P but not-R = P + ([P + R] is expected) + not-R = (Q + not-R) + ([Q + not-R + R] is expected) + not-R.

Hearing this in isolation, an informant’s first reaction might be ‘ If P, who would expect R? ’ since P already implies not-R. Again, the hearer might resolve the conflict similarly to 8.4.2 (a)-(e) above: (a) He may reject the utterance: ‘You must think that (it’s possible to say that) a person sometimes loses something intentionally, but that’s not so.’ (b) Denial of previous assertion: ‘ Someone must have said that it was intentional.’ (c) Variant version of the code, (d) Interpretation of irony: replace ‘not-R’ with ‘R’ as in ‘He’s lost his watch, so he says, but it was intentional.’ (e) Interpretation of a lapse: rephrase P but not-R as P and not-R, thus eliminating ‘ (P + R) is expected ’, as in ‘ Well yes, of course: he lost his watch and didn’t do so intentionally.’

Thus, both sentences of the test pair

(15) (a) He lost it but didn’t do so intentionally

(b) He lost it but did so intentionally

are initially confusing since a criterial component is involved, but when pressed for a possible interpretation, an informant might consider (15 b) as describing deceptive behavior. Interpreting deception is easier where such an unobservable as intention is involved. It is harder where intentions are not questioned, as in the initially confusing test pair

(16) (a) He got himself one but didn’t do anything to get it

(b) He got himself one but did something to get it

where ‘A does something to get B ’ (‘ [A an-F] causes [B is anRh A] ’) is criterial to A gets self B. When presented with such a test pair as (16), it has occurred in work on various languages that an informant, in the confusion of choosing between two unclear sentences, has selected the one in which the but-clause does at least negate a previously occurring element, even though the latter is a criterial component of the first clause. However, when asked for a possible interpretation or situation of occurrence of the selected sentence, an informant has often concluded that it is actually contradictory, thus supporting the criteriality of the hypothesized component.

We take up another use of the but-test, as in:

(17) (a) He lost it, but it was his

(b) He lost it, but it wasn’t his.

‘A has B before (time) T ’ does seem to be a component of A loses B at T, but this pair of sentences tests for the more restricted element ‘ B is A’s before T ’, which is more doubtful, but still a candidate. The effect of the two sentences is not what would be expected if a criterial component were involved, as described in 8.4.2-3 above, yet they do not offer a clearcut choice as to which makes more sense. Each requires a hearer to imagine a background context in order to be interpretable. For (17 a), for example, this could be that ‘it’ might have been someone else’s and that it is undesirable to lose others’ possessions. For (17 b) the background information could be the converse. Whichever background is supplied would make the corresponding sentence rank higher. If ‘it was his’ were already a connotation of ‘he lost it’, no background would need to be added, and (17 b) should most often be ranked higher by informants. Thus the but-test may also be useful for identifying nonconnotations, as well as, perhaps, disjunctive connotations that are contradictories of each other.6

A sentence such as The pickpocket lent the judge a gold watch, but it was the judge's [watch] illustrates, perhaps in the extreme, how the value of informant judgments can suffer due to interference if other sentence constituents than the tested item (here, lend) are not fairly neutral, especially when testing for criteriality. Generality is desirable particularly when using P but R and is achieved in the testing of verbs, for example, by employing pronouns or their equivalents rather than nouns.

1 Ariel’s (1967) critique of the tests of ch. 2 in Bendix 1966 gives valuable warnings and suggestions for anyone who would use semantic tests uncritically or as operational procedures. His otherwise useful discussion is marred by an a priori approach which would prejudice an empirical descriptive semantics.

2 For lend, this and other tests contrasting it with other verbs, its possible collocations and referents, etc. might yield the definition C lends B to A — ‘ B is an-Rh C ’ + ‘ B not-is A’s ’ + ‘ (C an-F) causes ([B is an-Rh A] + [(B is A’s) not-comes to be])’, or roughly ‘ C has B ’ and ‘ B is not A’s’ and ‘ C causes A to have B without B becoming A’s’. Without repetition of the existential quantifier in the second occurrence of ‘ B is an-Rh A’, namely as ‘ B is Rh A’, the false implication would be that ‘ B ’ must be in the same relation to ‘ A ’ as it is to ‘ C ’. Further, with our formulation, any assertion C lends B to A implies that ‘ B ’ is such that it can be had in two different ways, i.e. that it is possible for ‘A’ to have ‘B’ either without ‘B’ being ‘A’s or with ‘ B ’ being ‘-A’s, thus accounting for the initial anomaly of C lends A a cold, a black eye, etc.

3 Similarly, for a definition ‘P = Q or R’, we read “ If someone asserts ‘P’, he is asserting ‘ Q + R’ or ‘Q ’ or ‘ Rand not “ If someone asserts ‘ P’, he is asserting ‘ Q or R’.” The symbols in a definition stand for types, and not for tokens, and it is tokens which actually convey assertions. Thus, for ‘P = Q or R’: ‘not-P = not-(Q or R) = not-Q or not-R’. In such a disjunctive case, the negation is treated distributively for types and is not read as ‘ not-(Q or R) = not-Q + not-R ’. The latter reading deals with tokens and represents an equivalence of assertions. That is, for ‘ P = Q or R ’: ‘ (not-P)i = not-Q + not-R ’ and ‘ (not-P)j = not-Q ’ and ‘(not-P)k = not-R’.

4 ‘ Not intentionally ’ rather than ‘ unintentionally ’ since ‘ A ’ in A loses B can be inanimate: Her hair has lost its silken sheen. Wide vs. narrow scope of negation indicates no necessary applicability vs. applicability respectively of the dimension ‘intention’ to ‘A’, as in ‘not-(A intends. . .)’ vs. ‘A not-intends. . .’. Cf. Zimmer 1964: 21-6.

5We describe this replacement as a change from ‘ The referent of Pi is a member of the class of events defined by P ’ to ‘ The referent of Pi, which is a member of the class of events defined by Q + R, is (meant to appear) like a member of the class of events defined by P.’

6 Ariel (1967: 544) has issued a warning that should be taken seriously when applying the but-test: this test could identify disjunctive criterial components as connotations. To use his example, (b) would rank higher in: John is a postman, (a) but he delivers packages /(b) but he does not deliver packages, where postman may be defined as ‘ a man whose job is to deliver letters and/or packages’. Thus, ‘deliver packages’ could be mistaken as a connotation when, it is contended, it is an essential part of a criterial component that is an inclusive disjunction. The example inadvertently illustrates another point: namely, disjunction can be a function of the analyst’s ingenuity. If Tetters and/or packages’ is reduced to ‘mail’, with a unitary definition, postman becomes ‘a man whose job is to deliver mail’, without any disjunction. Then connotational elements of ‘ mail ’ must be added to the criterifil components of ‘ mail ’ to arrive at ‘ packages’. The problem of descriptive semantics in the context of a prescriptive philosophical discourse is that a descriptive theory may find itself measured against a view of reality when in fact we are dealing with contending theories about a body of data, measured against an evaluating metatheory of description.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)