Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The nature of passive

المؤلف:

R.M.W. Dixon

المصدر:

A Semantic approach to English grammar

الجزء والصفحة:

354-11

2023-04-16

1306

The nature of passive

Everything else being equal, a speaker of English will prefer to use a verb with two or more core roles (a transitive verb) in an active construction, with subject and object stated. A passive construction may be employed in one of the following circumstances:

- To avoid mentioning the subject

A surface subject is obligatory in each non-imperative English sentence. It is always possible to put someone or something in the subject slot, but such an indefinite form serves to draw attention to the fact that the subject is not being specified as fully as it might be. The passive may be used (a) if the speaker does not know who the subject was, e.g. Mary was attacked last night; or (b) if the speaker does not wish to reveal the identity of the subject, e.g. It has been reported to me that some students have been collaborating on their assignments; or (c) the identity of the subject is obvious to the addressees and does not need to be expressed, e.g. I’ve been promoted; or (d) the identity of the subject is not considered important.

Heavy use of the passive is a feature of certain styles; in scientific English it avoids bringing in the first person pronoun, e.g. An experiment was devised to investigate . . . rather than I devised an experiment to investigate . . . This is presumably to give an illusion of total objectivity, whereas in fact the particular personal skills and ideas of a scientist do play a role in his work, which would be honestly acknowledged by using active constructions with first person subject.

- To focus on the transitive object, rather than on the subject

We enunciated the semantic principles that underlie the assignment of semantic roles to syntactic relations, and stated that the role which is likely to be most relevant to the success of the activity will be placed in A (transitive subject) relation.

We can construct a referential hierarchy, going from first person pronoun, through second person, proper names of people, human common nouns with determiner or modifier indicating specific reference (e.g. that old man, my friend), human common nouns with indefinite reference, to inanimate nouns. It is certainly the case that a transitive subject is likely to be nearer the beginning of the hierarchy than its co-occurring object, e.g. I chose the blue cardigan, You should promote John, My teacher often canes boys, The fat girl is eating an ice cream.

However, the object can—in some particular instance of the activity—be nearer the beginning of the hierarchy than the subject. In such a circumstance the passive construction may be used, putting the role which is in underlying O relation into the surface S slot. Thus, in place of A boy kicked Mary at the picnic, the passive Mary was kicked (by a boy) at the picnic might be preferred. Similar examples are: Guess what, you have been chosen (by the team) as captain, I got promoted, My best friend often gets caned. Compare these with prototypical transitive sentences (subject above object on the hierarchy), for which a passive sounds most odd, e.g. The blue cardigan was chosen by me, An ice cream is being eaten by the fat girl.

We mentioned that if there are several non-A roles, any of which could potentially be coded onto O relation, then one which has specific reference is likely to be preferred over others which have non-specific reference (e.g. John told the good news (O: Message) to everyone he met, but John told Mary (O: Addressee) something or other). In the same spirit, an O NP which has specific reference is more likely to be amenable to passivization than one which is non-specific. For example, Our pet dog was shot by that new policeman sounds much more felicitous than A dog was shot by that new policeman (here the active would surely be preferred—That new policeman shot a dog).

3. To place a topic in subject relation

A discourse is normally organized around a ‘topic’, which is likely to recur in most sentences of the discourse, in a variety of semantic roles. There is always a preference for a topic to be subject, the one obligatory syntactic relation in an English sentence (and the pivot for various syntactic operations—see 4). If a topic occurs in underlying O relation then a passive construction may be employed, to put it in surface S slot, e.g. The hold-up man hid in the woods for five days, living on berries, and then he (underlying O, passive S) was caught and put in jail. (A topic NP is of course likely to have specific reference, demonstrating a correlation between criteria 2 and 3.)

4. To satisfy syntactic constraints

Every language has some syntactic mechanism for cohering together consecutive sentences in an utterance, identifying common elements and eliminating repetitions. English has a straightforward syntactic rule whereby, if two consecutive clauses have the same subject, this may be omitted from the second clause, e.g. John took off his coat and then (John) scolded Mary. However, if two coordinated clauses share an NP which is in subject relation in one and in object relation in another, then omission is not possible—from John took off his coat and then Mary scolded John, the final John cannot be omitted. In such circumstances a passive construction may be used; the NP which would be in O relation in an active transitive becomes subject of the passive and, in terms of the syntactic convention, can now be omitted, e.g. John took off his coat and was then scolded by Mary. (In English a pronoun may substitute for a repeated noun between coordinated clauses whatever the syntactic relations involved, and pronominalization would of course be used when omission of the NP is not permissible.)

Conditions 4 and 3 for using a passive are interrelated. If an object NP in one clause has been subject in a previous clause then it is functioning as topic for at least a small segment of the discourse, and will almost certainly have specific and individuated reference. On these grounds, quite apart from the speaker’s wanting to meet the syntactic condition on omission, it would be a prime target for passivization.

A reflexive clause—one in which subject and object are identical—is very unlikely to be cast into passive form, since none of the conditions just listed for using a passive can be satisfied: (1) it is impossible to avoid mentioning the subject, since it is identical with the object; (2) it is not meaningful to focus on object rather than on subject, since they are identical; and (3)–(4) there is no advantage in moving O into surface subject slot, since it is already identical with the subject. If a reflexive passive is ever used it is likely to be an ‘echo’ of a preceding sentence in the discourse that was in passive form, e.g. My brother was taught linguistics by Kenneth Pike, followed by Oh really! Well my brother’s a better linguist than yours and he was taught by himself.

5. To focus on the result of the activity

The passive construction involves a participial form of the verb which functions very much like an adjective; it forms a predicate together with copula be or get. This participle is also used to describe the result of the activity (if it does have a definite result). A passive construction may be used in order to focus on this result, e.g. My neighbor was appointed to the board (by the managing director), The goalkeeper is being rested from next week’s game, That cup was chipped by Mary when she washed the dishes.

There are two possibilities for the first element in a passive VP—be and get. Be is the unmarked form and—as discussed, may be used with a wider range of verbs than get. It seems that get is often used when the speaker wishes to imply that the state which the passive subject (deep O) is in is not due just to the transitive subject, or to the result of chance, but may in some way be due to the behavior of this passive subject. Consider John was fired—this could be used if there was a general redundancy in the firm. But John got fired implies that he did something foolish, such as being rude to his supervisor, which would be expected to lead to this result.

The verb get has a wide range of senses: (i) it is a member of the OWN subtype of GIVING, e.g. Mary got a new coat; (ii) get to has an achievement sense, as a member of the SEMI-MODAL type, e.g. John got to know how to operate the machine; (iii) it is a member of the MAKING type, e.g. I got John to write that letter to you; (iv) it can be a copula before an adjective or it can begin a passive VP, in both cases generally implying that the surface subject was at least partly responsible for being in a certain state, e.g. Johnny got dirty, Mary got promoted.

In fact the copula/passive sense, (iv), can plausibly be related to the causative sense, (iii). We can recall that, as a member of the MAKING type, get takes a Modal (FOR) TO complement clause, and the for must be omitted, e.g. The boss got Mary to fire John. The complement clause can be passive and to be may then be omitted under certain semantic conditions; thus, The boss got John fired.

Now the object of a MAKING verb (which is underlying subject of the complement clause) is not normally coreferential with the main clause subject; if it is it cannot, as a rule, be omitted; that is, we may say John forced himself to be examined by a specialist, but not *John forced to be examined by a specialist.

Thus, a normal MAKING complement construction would be John got himself fired. I suggest that the get passive is related to this, through the omission of himself. The point is that this omission—of main clause object (= complement clause subject) when it is coreferential with main clause subject—is not allowed for other MAKING verbs, but is put forward as a special syntactic rule which effectively derives a get passive from a MAKING construction involving get. This formulation states that an underlying get (MAKING verb) plus reflexive pronoun plus to (complementiser) plus be (unmarked passive introducer) plus passive verb can omit both the to be and the reflexive pronoun, and get then appears to be the marker of a variety of passive, parallel to be. (In fact, this explanation mirrors the historical development of the get passive in English; see Givo´n and Yang 1994.)

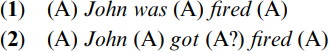

This analysis explains the distinctive meaning of get passives. Syntactic support is provided by the possible positioning of a sentential adverb such as recently. This can occur at the places marked by ‘(A)’ in:

Some speakers will accept John got (A) fired but it is much less acceptable than John (A) got fired. *John (A) was fired is judged as ungrammatical.

With an active predicate a sentential adverb can come after the first word of the auxiliary; if there is no auxiliary, it will immediately follow a copula but immediately precede a non-copula verb. Thus, with a canonical passive, involving be, an adverb may come between the passive auxiliary be and the passive verb (as in (1)) but not between the subject and be. In a causative construction with a passive complement clause the adverb placement is as shown in: (A) Mary (A) got John to be (A) fired (A). When the to be is omitted, with causative get, the adverb position which immediately followed to be becomes less acceptable, e.g. (A) Mary (A) got John (A?) fired (A). We suggested that the get passive is essentially a reflexive version of this construction, i.e. (A) John (A) got (himself) (A?) fired (A). This precisely explains the adverb possibilities in (2). (Note that when the himself is dropped, the adverb position immediately before fired becomes even more marginal than it was before.)

Although the get passive thus appears to be syntactically related to the MAKING verb get, it has now taken on a wider range of meaning, and does not always imply that the passive subject is partly responsible for being in the described state. That meeting got postponed, for instance, could not felicitously be expanded to That meeting got itself postponed, although it does carry a certain overtone that the meeting seems fated never to be held. The get passive is certainly more used in colloquial than in formal styles. I have the feeling that a by phrase is less likely to be included with a get passive than with a be passive (even in the same, colloquial style); this is something that would need to be confirmed by a text count. Get passives may also carry an implication that something happened rather recently— one might hear He got run over concerning something that occurred last week, but for something that took place ten years ago He was run over would be a more likely description.

Returning now to our general discussion of the nature of the passive, we can conclude that almost anything can be stated through an active construction but that only rather special things are suitable for description through a passive construction. For instance, there may be some special significance to the object NP, as it is used with a particular verb, or with a particular verb and a certain subject.

Consider John’s mother saw a brick in the bar. The passive correspondent of this, A brick was seen by John’s mother in the bar, sounds ridiculous, something that is most unlikely to be said. But if the event reported were John’s mother saw him in the bar, then the passive, John was seen (by his mother) in the bar, is perfectly feasible. If the passive were used one might guess that he shouldn’t have been there, and may now get into trouble. ‘John’ is a definite, individual human, a prime candidate to be in the subject relation. Casting the sentence into passive form implies that the concatenation of John’s being in the bar and his mother’s seeing him there has a particular significance.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)