Nominalizations and possession

Possession

I was once conducting a class on the Aboriginal languages of Australia and, for every grammatical topic, I’d enquire of each participant ‘How is this shown in your language?’, referring to the language they were investigating. One student came to me after class and requested: ‘Could you please not refer to ‘‘our languages’’. They don’t belong to us but to the Aboriginal community.’

The student assumed that the use of a possessive form (a possessive pronoun or a noun phrase marked by ’s) is equivalent to a claim of ownership. In fact it extends far beyond. In brief, a possessive form is used for:

(a) An alienable possession, something that the possessor does own—John’s car, Mary’s ring, my dog.

(b) A kin relation (whether consanguineal or affinal)—my mother, Mary’s husband.

(c) An inalienable part of the possessor—John’s foot, the tree’s blossom, my name.

(d) An attribute of the possessor—Mary’s age, your jealousy, John’s good character, Bill’s idea.

(e) Something typically associated with the possessor—Mary’s hometown, my dentist, your boss. Note that John’s firm is ambiguous. It could refer to the firm John works for or invests in (something associated with John), or it could be a firm which John owns, being then possession of type (a).

It will be seen that only (a) implies ownership. You could not be said to own your mother or your foot or your age or your dentist. There is in fact wide latitude for using a possessive form in sense (e). A colleague once said to me that she’d read something in, as she put it, ‘your New Yorker’. Now I don’t own this magazine, and didn’t even have a copy of (or have seen) the issue being quoted from. But I did, at that time, often read The New Yorker and set high credence upon it. The colleague was, effectively, saying ‘I read this in The New Yorker, a magazine which I associate with you.’

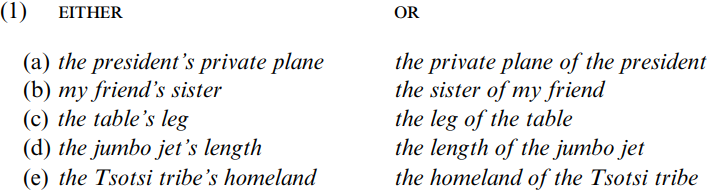

When a possessor is a noun phrase (which can be just a noun) there are, in fact, two ways of marking it—by suffix ’s on the possessor (which precedes the possessed) or by the preposition of before the possessor (which follows the possessed). One can say:

However, there is only sometimes a choice between’s and of. For instance, it is in most circumstances infelicitous to say the car of John, the husband of Mary, the foot of Bill, the anger of Jane, the dentist of Fred. (And one could never use of in place of a possessive pronoun; for example, my car could not be rephrased as *the car of me.)

In essence, the ’s alternative is preferred (and the of alternative dispreferred) according as:

(i) The possessor is human (or at least animate), specific and singular. A proper name always takes ’s. And whereas the boy’s leg is preferred over the leg of the boy (singular human possessor), the legs of the boys (plural human possessor) is more acceptable, with the legs of the antique tables (plural inanimate possessor) sounding better still.

(ii) The possessed is specific and singular. For example, my friend’s sister is preferred over the sister of my friend (singular possessed) but the sisters of my friend (plural possessed) sounds considerably better.

(iii) The possessor has few words. The ’s alternative is not liked on a long possessor, and here of may be preferred. For example, the gun of that evil character who lives in the tumbledown shack down the road, rather than that evil character who lives in the tumbledown shack down the road’s gun.

(iv) The possessor is familiar information. For instance, in a discussion about my wife I might say my wife’s jewels, since my wife is familiar information and this is the first mention of the jewels. But if in a discussion about jewels I suddenly mention those belonging to my wife, I would be more likely to say the jewels of my wife, since this is the first mention of my wife (it is not familiar information).

Thus, for some instances of possession only ’s is considered felicitous. For others—such as those in (1)—either ’s or of is acceptable. And for others only of is likely to be used in normal circumstances; for example, one hears the names of mountains, the virulence of the mosquitoes, the haunts of evil spirits. (There are just a few idiomatic phrases which transgress principles (i) and (ii); for example, one generally says a summer’s day rather than a day of summer.)

A possessive modifier (noun plus ’s, or a possessive pronoun) is mutually exclusive with the article a and demonstratives, this, that, these, those. But one might want to include both a or a demonstrative and a possessive modifier in the same noun phrase. This is achieved by placing the possessive modifier after the head of the noun phrase, linked to it by of. Thus John’s picture but a picture of John’s; my picture but that picture of mine. Here the possessive relation of is shown by ’s or mine, with the of simply a linker. One can also say a picture of John, but this has a quite different meaning. Whereas a picture of John’s is a picture belonging to John, a picture of John is a picture for which John was the subject (it may well belong to someone else).

The preposition of shows a wide range of uses beyond that of marking possession. It can introduce a predicate argument, as in jealous of his rival, fond of golf, dream of Dinah. It is used to indicate quantity or material—all of the boys, six kilos of potatoes, eight years of war, the value of these artefacts, a cup of tea, a skirt of grass. It takes part in other grammatical constructions, as in a giant of a man, less of a fool. And it is a constituent of a number of complex grammatical markers, such as out of, in terms of and in view of.

‘possessive construction’ will be used in a narrow sense to refer only to possession marked by ’s (or by a possessive pronoun).

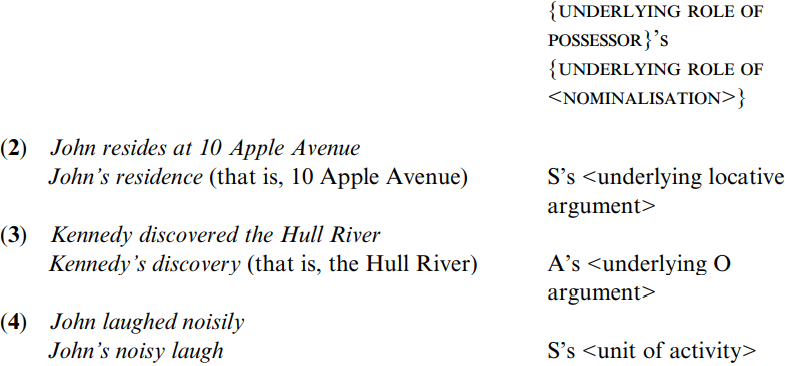

English has a rich range of derivational processes which form a nominal from a verb—these are nominalizations, and they have a close link with possession. A noun phrase which is in S, A, O or indirect object function to a verb may become possessor of a nominalization based on that verb. For example:

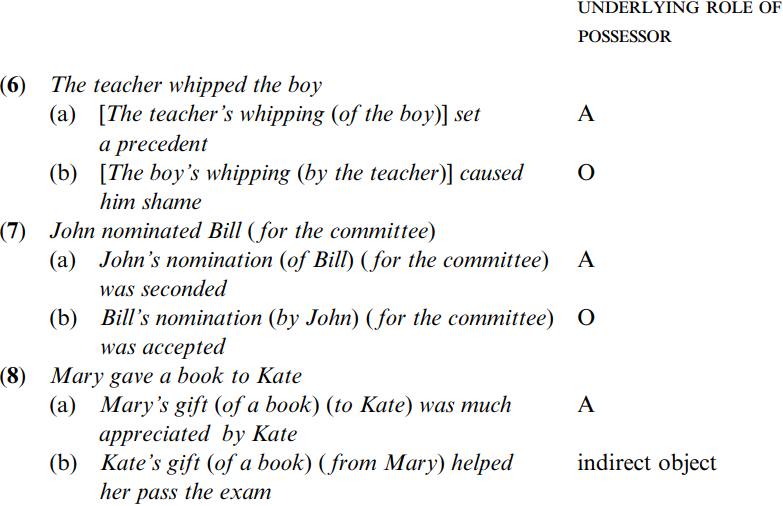

There may be nominalizations relating to both A and O, linked by possessive marker to O and A respectively:

There are a number of instances where a possessive construction involving a nominalization is ambiguous. Consider:

The ambiguity can extend further; for example, John’s painting could be something done by John (John painted X) or something done of John (X painted John). Or it could be neither of these, but instead a painting owned by John (painted by someone other than John, and of someone or something other than John).

It will be seen that a nominalization can refer to one of a number of aspects of the basic sentences it is associated with—employer in (5b) is a volitional agent; discovery in (3), employee in (5c) and gift in (8) are all underlying objects; and residence in (2) is a locus. In contrast, whipping in (6) refers to an activity, while laugh in (4) and nomination in (7) refer to a unit of activity.

There are a multitude of morphological processes for nominalization. In the case of verbs of Germanic origin (henceforth called Germanic verbs), the plain root may be used (zero derivation), as with laugh in (4). Verbs of Romance origin (from Latin or early stages of French; henceforth, Romance verbs) typically take a suffix—residence in (2), discovery in (3), nomination in (7). Agentive nominalizations are typically marked by -er on both Germanic and Romance verbs, as employer in (5b), while some object nominalizations are shown by -ee, as employee in (5c). We find –ing on many Germanic and some Romance verbs, as whipping in (6). Finally, there are a number of irregular derivations of ancient origin, such as gift in (8).

We outlined the nine major types of deverbal nominalization, their meanings, criteria for recognizing and distinguishing them, and whether they automatically enter into a possessive construction with an argument from the underlying clause. We surveyed the morphological processes involved, their phonological forms, and the types of nominalization each relates to. The fascinating question of how phrasal verbs form nominalizations was explored. Then we dealt in turn with the verbal semantic types, indicating which varieties of nominalization (and which realizations) are associated with each.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة