Types associated with the Adjective class

The following semantic types are associated with the grammatical class Adjective in English:

1. DIMENSION, e.g. big, great, short, thin, round, narrow, deep.

2. PHYSICAL PROPERTY, e.g. hard, strong, clean, cool, heavy, sweet, fresh, cheap, quiet, noisy; this includes a CORPOREAL subtype, e.g. well, sick, ill, dead; absent; beautiful, ugly.

3. SPEED—quick (at), fast (at), slow (at), rapid, sudden.

4. AGE—new, old, young, modern.

5. COLOR, e.g. white, black, red, crimson, mottled, golden.

6. VALUE, e.g. (a) good, bad, lovely, atrocious, perfect; (b) odd, strange, curious; necessary, crucial; important; lucky.

7. DIFFICULTY, e.g. easy, difficult, tough, hard, simple.

8. VOLITION, e.g. deliberate, accidental, purposeful.

9. QUALIFICATION, with a number of subtypes:

(a) DEFINITE, a factual qualification regarding an event, e.g. definite, probable, true, obvious;

(b) POSSIBLE, expressing the speaker’s opinion about an event, which is often some potential happening, e.g. possible, impossible;

(c) USUAL, the speaker’s opinion about how predictable some happening is, e.g. usual, normal, common;

(d) LIKELY, again an opinion, but tending to focus on the subject’s potentiality to engineer some happening, e.g. likely, certain;

(e) SURE, as for (d), but with a stronger focus on the subject’s control, e.g. sure;

(f) CORRECT, e.g. correct, right, wrong, appropriate, sensible. These have two distinct senses, commenting (i) on the correctness of a fact, similar to (a) (e.g. That the whale is not a fish is right), and (ii) on the correctness of the subject’s undertaking some activity (e.g. John was right to resign).

10. HUMAN PROPENSITY, again with a number of subtypes:

(a) FOND, with a similar meaning to LIKING verbs, e.g. fond (taking preposition of);

(b) ANGRY, describing an emotional reaction to some definite happening, e.g. angry (with/at/about), jealous (of), mad (about), sad (about);

(c) HAPPY, an emotional response to some actual or potential happening, e.g. anxious, keen, happy, thankful, careful, sorry, glad (all taking about); proud, ashamed, afraid (all taking of);

(d) UNSURE, the speaker’s assessment about some potential event, e.g. certain, sure, unsure (all taking of or about), curious (about);

(e) EAGER, with meanings similar to WANTING verbs, e.g. eager, ready, prepared (all taking for), willing;

(f) CLEVER, referring to ability, or an attitude towards social relations with others, e.g. clever, adept, stupid; lucky; kind, cruel; generous (all taking at);

(g) HONEST, judgement of some person or statement as fair and just, e.g. honest (about/in/at), frank (in);

(h) BUSY, referring to involvement in activity, e.g. busy (at/with), occupied (with), preoccupied (with), lazy (over).

11. SIMILARITY, comparing two things, states or events, e.g. like, unlike (which are the only adjectives to be followed by an NP with no preposition); similar (to), different (from), equal (to/with), identical (to), analogous (to), separate (from), independent (of), consistent (with) (which introduce the second role—obligatory for an adjective from this type—with a preposition).

Almost all the members of DIMENSION, PHYSICAL PROPERTY, SPEED, AGE, DIFFICULTY and QUALIFICATION are basic adjectives (dead, derived from a verb, is an exception). Many of the less central COLOR terms are derived from nouns, e.g. violet, spotted. There are a fair proportion of adjectives derived from verbs in the VALUE and VOLITION types (e.g. interesting, amazing, desirable, accidental, purposeful) and some in the HUMAN PROPENSITY and SIMILARITY types (e.g. thankful, prepared, different). A few words in VALUE and HUMAN PROPENSITY are derived from nouns (e.g. angry, lucky).

These eleven Adjective types do have rather different grammatical properties. The prefix un- occurs with a fair number of QUALIFICATION and HUMAN PROPENSITY adjectives, with some from VALUE and a few from PHYSICAL PROPERTY and SIMILARITY, but with none from DIMENSION, SPEECH, AGE, COLOR, DIFFICULTY or VOLITION. The verbalizing suffix -en is used with many adjectives from types 1–5 but with none from 6–9 (toughen and harden relate to the PHYSICAL PROPERTY sense of these lexemes) and with none save glad and like from 10 and 11 respectively. Derived adverbs may be formed from almost all adjectives in SPEED, VALUE, VOLITION, DIFFICULT, QUALIFICATION, HUMAN PROPENSITY and SIMILARITY and from some in PHYSICAL PROPERTY but from none in AGE; adverbs based on adjectives in DIMENSION and COLOUR tend to be restricted to a metaphorical meaning (e.g. warmly commend, dryly remark, darkly hint). When adjectives co-occur in an NP then the unmarked ordering is: 11–9– 8–7–6–1–2–3–10–4–5.

An adjective will typically modify the meaning of a noun, and can be used either as modifier within an NP (That clever man is coming) or as copula complement (That man is clever); only a few adjectives allow just one of these syntactic possibilities. Notably, most adjectives commencing with a- (such as asleep, aghast, afraid) can only occur as copula complement, not as modifier; this is because the a- goes back to a preposition an ‘in, on’ in Middle English.

DIMENSION, PHYSICAL PROPERTY, COLOR and AGE adjectives typically relate to a CONCRETE noun. SPEED can modify a CONCRETE or an ACTIVITY noun. HUMAN PROPENSITY adjectives, as the label implies, generally relate to a HUMAN noun. DIFFICULTY, VOLITION and QUALIFICATION adjectives tend to refer to an event, and may have as subject an appropriate noun (e.g. Cyclones are common at this time of year) or a complement clause. VALUE adjectives may refer to anything; the subject can be any kind of noun, or a complement clause. There is a tendency for a THAT or Modal (FOR) TO complement clause in subject function (which is a ‘heavy constituent’) to be extraposed to the end of the main clause, and replaced by it—compare The result was strange with It was strange that Scotland won, which sounds a little more felicitous than That Scotland won was strange. SIMILARITY adjectives relate together two things that can be CONCRETE, ABSTRACT or ACTIVITIES (but should normally both come from the same category).

VALUE adjectives may take as subject an ING or THAT complement clause (a THAT clause will generally be extraposed), e.g. Mary’s baking a cake for us was really lovely, It is lucky that John came on time. Subset (b) of the VALUE type may also take a Modal (FOR) TO subject complement, e.g. It was necessary/odd for John to sign the document. DIFFICULTY adjectives may take as subject a Modal (FOR) TO clause, again generally extraposed, e.g. It is hard for Mary to operate our mower. Both VALUE and DIFFICULTY types can also take in subject relation a complement clause which has no subject stated (it is understood to be ‘everyone/anyone’). This applies to ING clauses for VALUE adjectives, e.g. Helping blind people is good, and to both Modal (FOR) TO and ING clauses for DIFFICULTY adjectives, e.g. Operating our mower is hard, It is hard (sc. for anyone) to operate our mower.

VALUE and DIFFICULTY adjectives occur in a further construction, one in which what could be object of a complement clause functions as subject of the adjective, with the rest of the complement clause following the adjective, introduced by to, e.g. That picture is good to look at, Our mower is easy to start. For the DIFFICULTY type it is tempting to derive Our mower is easy to start from It is easy to start our mower, by ‘raising’ the complement clause object to become main clause subject. However, this derivation is not available for some adjectives from the VALUE type which do not take a Modal (FOR) to clause in subject slot.

VOLITION adjectives typically have an ING complement clause as subject; for example, John’s spilling the milk was accidental.

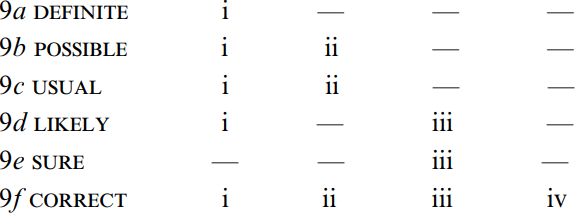

The various subtypes within QUALIFICATION differ in the kinds of complement clause they accept. The overall possibilities are:

- a THAT complement as subject, often extraposed, e.g. That John will win is probable, It is probable that John will win;

- a Modal (FOR) to complement as subject, normally extraposed, e.g. It is unusual for a baby to be walking at twelve months;

- a variant of (ii), where the complement clause subject is raised to fill main clause subject slot, replacing it (and for is then dropped), e.g. A baby is likely to walk by twenty-four months, John was wrong to resign;

- an ING complement clause (often with the subject omitted) in subject slot, e.g. (Your) taking out accident insurance was sensible.

The QUALIFCATION subtypes occur with subject complements as follows:

Some pairs of QUALIFICATION adjectives which might appear to have similar meanings do in fact belong to different subtypes, and show distinct syntactic properties. Compare definite (from 9a) and certain (from 9d):

(1a) It is certain that the King will visit us this month

(1b) It is definite that the King will visit us this month

(2a) It is certain that the monsoon will come this month

(2b) *It is definite that the monsoon will come this month

Sentence (1b) implies that an announcement has been made; the speaker uses definite to report this. In contrast, (1a) presents an opinion (albeit a very strong one)—from all the signs of preparation, the King must be about to make this visit. One can say (2a), using certain to qualify an inference made from study of meteorological charts etc. But (2b) is an inappropriate sentence, simply because there is no ordinance that rains will come at a particular time.

Now compare possible (from 9b), likely (from 9d) and sure (9e):

(3a) That John will win the prize is possible

(3b) That John will win the prize is likely

(3c) *That John will win the prize is sure

(4a) *John is possible to win

(4b) John is likely to win

(4c) John is sure to win

Both possible and likely may comment on the chance of some event happening, as in (3a/b). Likely differs from possible in that it can focus on the outcome as due to the eVorts of the subject—hence (4b) but not *(4a). When sure is used with a human subject it always focuses on the subject’s eVort, hence the unacceptability of *(3c).

HUMAN PROPENSITY adjectives normally have a HUMAN noun as subject. They can be followed by a preposition introducing a constituent that states the reason for the emotional state; this may be an NP or a complement clause, e.g. John was sorry about the delay, John was sorry about being late, John was sorry that he was late, John was sorry to be late. The preposition drops before that or to at the beginning of a complement clause, but is retained before an ING clause.

The various subtypes of HUMAN PROPENSITY have differing complement possibilities:

10a. FOND only accepts an NP or ING complement, e.g. I’m fond of watching cricket.

10b. ANGRY takes an NP or a THAT or ING clause, e.g. She’s angry about John(’s) being officially rebuked, She’s angry that John got the sack.

10c. HAPPY takes an NP or ING or THAT or Modal (FOR) TO (complement clause subject, and for, is omitted when coreferential with main clause subject), e.g.

I’m happy about the decision, I’m happy about (Mary(’s) ) being chosen, I’m happy that Mary was chosen, I’m happy (for Mary) to be chosen.

10d. UNSURE takes an NP or a THAT clause for its positive members certain (of) and sure (of), e.g. I’m sure of the result, She’s certain that John will come; but an NP or a WH- clause after those members that indicate uncertainty, unsure (of) and curious (about), e.g. I am unsure of the time of the meeting, She is curious (about) whether John will attend (or after positive members when not is included, e.g. I’m not certain whether he’ll come).

10e. EAGER takes an NP or a THAT or Modal (FOR) TO complement, e.g. I’m eager for the fray, I’m eager that Mary should go, I’m eager (for Mary) to go. Ready may only take an NP or a Modal (FOR) TO clause (not a THAT complement) while willing must take a THAT or Modal (FOR) TO clause, i.e. it cannot be followed by preposition plus NP.

10f. CLEVER shows wide syntactic possibilities. Firstly, like other HUMAN PROPENSITY adjectives, a member of the CLEVER subtype may have a HUMAN noun as subject, and a post-predicate prepositional constituent, e.g. John was very stupid (about ignoring the rules/in the way he ignored the rules). Alternatively, there may be a complement clause as subject, with of introducing an NP that refers to the person to whom the propensity applies—either a THAT clause, e.g. That John came in without knocking was very stupid (of him), or a Modal (FOR) TO clause, e.g. For John to come in without knocking was very stupid (of him), To come in without knocking was very stupid of John, It was very stupid of John (for him) to come in without knocking, It was very stupid for John to come in without knocking. (Note that of John and for John can both be included—with the second occurrence of John pronominalized—or either of these may be omitted.) As with some QUALIFICATION subtypes, the subject of an extraposed Modal (FOR) TO subject complement can be raised to become subject of the main clause, replacing impersonal it, e.g. John was stupid to come in without knocking.

10g. HONEST has very similar properties to stupid, shown in the last paragraph. For example, That John declared his interest was honest (of him), For John to declare his interest was honest (of him), It was honest of John (for him) to declare his interest and John was honest to declare his interest. The adjective frank has more limited possibilities; for example John was frank in/about declaring his interest.

10h. BUSY adjectives may take an NP or an ING complement clause; for example, John was busy with the accounts, Mary was occupied with cooking jam, Fred was lazy at getting things done.

SIMILARITY adjectives have similar meaning and syntax to COMPARING verbs. There may be NPs or ING complement clauses, with comparable meanings, in subject slot and in post-predicate slot, e.g. John is similar to his cousin, Applying for a visa to enter Albania is like hitting your head against a brick wall.

Semantic explanation for the differing complement possibilities of the various adjectival types.

Some adjectives have two distinct senses, which relate to distinct types. We have already mentioned tough and hard, which belong to both PHYSICAL PROPERTY (This wood is hard) and DIFFICULTY (It was hard for John to bring himself to kiss Mary). Curious is in one sense a VALUE adjective, taking a THAT complement in subject function, e.g. The result of the race was rather curious, That Mary won the race was rather curious. In another sense, curious (about) belongs to the UNSURE subtype of HUMAN PROPENSITY, e.g. John was curious about the result of the race, John was curious (about) whether Mary won the race. Sure and certain belong both to QUANTIFICATION (That Mary will win is certain) and also to the UNSURE subtype (John is certain that he/Mary will win).

As mentioned above, many adjectives from the DIMENSION, PHYSICAL PROPERTY, SPEED, AGE and COLOR types form derived verbs by the addition of -en. These generally function both intransitively, with the meaning ‘become’, e.g. The road widened after the state boundary ‘the road became wide(r) . . . ’, and transitively, with the meaning ‘make’, e.g. They widened the road ‘they made the road wide(r)’. The occurrence of -en is subject both to a semantic constraint—in terms of the types it can occur with—and also to a phonological constraint—only roots ending in  take -en. Adjectives from the appropriate types which do not end in one of these permissible segments may have the root form used as a verb, e.g. narrow can function as an adjective, as an intransitive verb ‘become narrow’ and as a transitive verb ‘make narrow’; clean and dirty may function both as adjectives and transitive verbs ‘make clean/dirty’. The two main VALUE adjectives, good and bad, have suppletive verbal forms improve and worsen, which are used both intransitively ‘become better/ worse’ and also transitively, ‘make better/worse’.

take -en. Adjectives from the appropriate types which do not end in one of these permissible segments may have the root form used as a verb, e.g. narrow can function as an adjective, as an intransitive verb ‘become narrow’ and as a transitive verb ‘make narrow’; clean and dirty may function both as adjectives and transitive verbs ‘make clean/dirty’. The two main VALUE adjectives, good and bad, have suppletive verbal forms improve and worsen, which are used both intransitively ‘become better/ worse’ and also transitively, ‘make better/worse’.

Whereas all (or almost all) languages have major word classes that can be labelled Noun and Verb, some do not have a major word class Adjective. A fair number of languages have a small, closed Adjective class, which generally comprises DIMESION, AGE, VALUE and COLOR. In such languages the PHYSICAL PROPERTY type tends to be associated with the Verb class (‘be heavy’, ‘be wet’, etc.) and the HUMAN PROPENSITY type with either the Noun class (‘cleverness’, ‘pride’, etc.) or the Verb class (‘be clever’, ‘be proud’, etc.). Many languages do not have words for QUALIFICATION as members of the Adjective class; they may be adverbs, or else grammatical particles.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة