Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

English orthography

المؤلف:

George Yule

المصدر:

The study of language

الجزء والصفحة:

218-16

4-3-2022

2341

English orthography

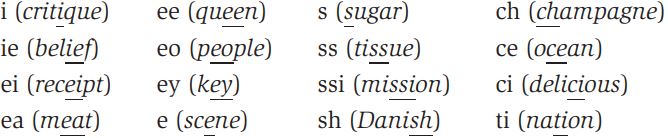

The orthography (or spelling) of contemporary English allows for a lot of variation in how each sound is represented. The vowel sound represented by /i/ is written in various ways, as shown in the first two columns on the left below, and the consonant sound represented by /ʃ/ has various spellings, as in the other two columns.

Notice how often in these two lists the single phoneme is actually represented by more than one letter. Part of the reason for this is that the English language is full of words borrowed, often with their spelling, from other languages, as in “ph” for /f/ in the Greek borrowings alphabet and orthography. Notice again the use of two letters in combination for a single sound. A combination of two letters consistently used for a single sound, as in “ph” /f/ and “sh” /ʃ/ is called a digraph.

The English writing system is alphabetic in a very loose sense. Some reasons for this irregular correspondence between sound and symbolic representation may be found in a number of historical influences on the form of written English. The spelling of written English was largely fixed in the form that was used when printing was introduced into fifteenth-century England. At that time, there were a number of conventions regarding the written representation of words that had been derived from forms used in writing other languages, notably Latin and French. For example, “qu” replaced older English “cw” in words like queen. Moreover, many of the early printers were native Dutch speakers and could not make consistently accurate decisions about English pronunciations, hence the “h” in ghost.

Perhaps more important is the fact that, since the fifteenth century, the pronunciation of spoken English has undergone substantial changes. For example, although we no longer pronounce the initial “k” sound or the internal “gh” sound, we still include letters indicating the older pronunciation in our contemporary spelling of the word knight. These are sometimes called “silent letters.” They also violate the one-sound-one-symbol principle, but not with as much effect as the “silent” final -e of so many English words. Not only do we have to learn that this letter is not pronounced, we also have to know the patterns of influence it has on the preceding vowel, as in the different pronunciations of “a” in the pair hat/hate and “o” in not/note

If we then add in the fact that a large number of older written English words were actually “recreated” by sixteenth-century spelling reformers to bring their written forms more into line with what were supposed, sometimes erroneously, to be their Latin origins (e.g. dette became debt, doute became doubt, iland became island), then the sources of the mismatch between written and spoken forms begin to become clear. Even when the revolutionary American spelling reformer Noah Webster was successful (in the USA) in revising a form such as British English honour, he only managed to go as far as honor (and not onor). His proposed revisions of bred (for bread), giv (for give) and laf (for laugh) were in line with the alphabetic principle, and are often the preferred forms of young children learning to write English, but they have obviously not found their way into everyday printed English.

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)