Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Compositionality

المؤلف:

Patrick Griffiths

المصدر:

An Introduction to English Semantics And Pragmatics

الجزء والصفحة:

17-1

10-2-2022

1127

Compositionality

We need to account for sentence meaning in order to develop explanations of utterance meaning, because utterances are sentences put to use. The number of sentences in a human language is potentially infinite; so our account cannot be a list of all the sentences with an interpretation written next to each one. We have to generalize, to try to discover the principles that enable people to choose sentences that can, as utterances in particular contexts, have the intended meanings and that make it possible for their addressees to understand what they hear or read.

Semanticists, therefore, aim to explain the meaning of each sentence as arising from, on the one hand, the meanings of its parts and, on the other, the manner in which the parts are put together. That is what a compositional theory of meaning amounts to. The meaningful parts of a sentence are clauses, phrases and words; and the meaningful parts of words are morphemes.

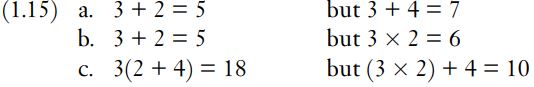

Consider an analogy from arithmetic: the numbers that go into a sum affect the answer, as in (1.15a); so do the operations such as addition and multiplication by which we can combine numbers (1.15b). With more than one operation, the order they are performed in can make a difference (1.15c), where round brackets enclose the operation performed first.

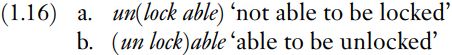

The examples in (1.16) show something similar in the construction of words from morphemes – similar but not identical, because this is not addition and multiplication, but an operation of negation or reversal performed by the prefix un-, and the formation of “capability” adjectives by means of the suffix -able.

The analysis indicated by the brackets in (1.16a) could describe a locker with a broken hasp. The one in (1.16b) could describe a locked locker for which the key has just been found. The brackets indicate the scope of the operations: which parts of the representation un- and -able operate on. In (1.16a) un- operates on lockable, but -able operates only on lock. In (1.16b) un- operates on just lock, and -able operates on unlock. The meaning differences based on scope differences in (1.16) are not a quirk of the word – or pair of words – unlockable. The same bracketing will yield corresponding meanings for unbendable, unstickable and a number of others.

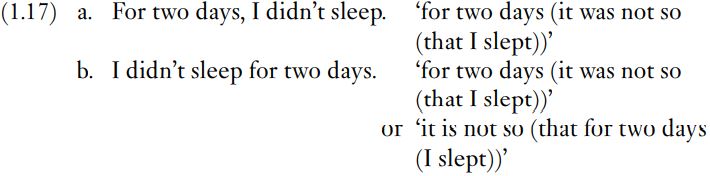

In syntax too there can be differences in meaning depending on the order that operations apply. Example (1.17a) is an unambiguous sentence. It covers the case of someone who was awake for two days. But (1.17b), containing the same words, is ambiguous, either meaning the same as (1.17a) or applying to someone who was asleep, but not for two days (possibly for only two hours or maybe for three days).

The ‘meanings’ indicated to the right of the examples are not in a standard notation. They are there to informally suggest how the overall meanings are built up. In (1.17a) the listener or reader first has to consider a negation of sleeping and then to think about that negative state – wakefulness – continuing for two days. To understand the second meaning given for (1.17b), first think what it means to sleep for two days, then cancel that idea. Syntactically, for two days is an adjunct in (1.17a) and also for the first of the meanings shown for (1.17b). When it is a complement to slept, we get the second meaning of (1.17b). Try saying (1.17b) with stress on two if you initially find the second meaning difficult to get.

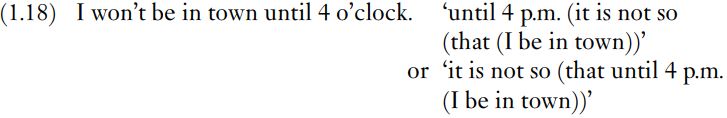

The interpretations in (1.17) are not one-off facts regarding a particular sentence about sleeping – or not sleeping – for two days. Other sentences involving the operation of negation and a prepositional phrase that is either an adjunct or a complement have corresponding meanings. For instance, when we lived in a village some distance from town, I once overheard a member of my family say (1.18) over the phone.

I couldn’t tell which of the meanings – parallel to the two given for (1.17b) – was intended: being out of town until 4 pm and arriving in town only then or later, or arriving in town at some earlier time and then not staying in town as late as 4 pm. If the speaker had instead said “Until 4 o’clock, I won’t be in town”, it would have been unambiguous, as with (1.17a).

Idioms are exceptions. An expression is an idiom if its meaning is not compositional, that is to say it cannot be worked out from knowledge of the meanings of its parts and the way they have been put together. Come a cropper means ‘fall heavily’ but we cannot derive this meaning from the meanings of come, a, crop and -er. Browned off (meaning ‘disgruntled’), and see eye to eye (meaning ‘agree’) are other examples. Idioms simply have to be learned as wholes. Ordinary one-morpheme words are also, in a sense, idioms. The best we can hope to do for the word pouch is to pair it with its meaning, ‘small bag’. The meaning of pouch cannot be worked out compositionally from the meaning of ouch and a supposed meaning of p.

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

الاكثر قراءة في Semantics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)