Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Morphophonemic changes

المؤلف:

PAUL R. KROEGER

المصدر:

Analyzing Grammar An Introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

P292-C15

2026-02-06

30

Morphophonemic changes

We can think of suppletion as a process which replaces one allomorph with another, as the name suggests. Morphophonemic change involves not replacing but changing the phonological shape of a morpheme. A morphophonemic process can be described as a change in one or more phonemes triggered by the phonological properties of a neighboring morpheme. A very familiar example occurs in the suffix that marks regular plurals in English.

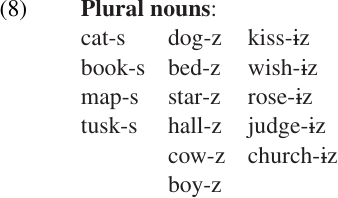

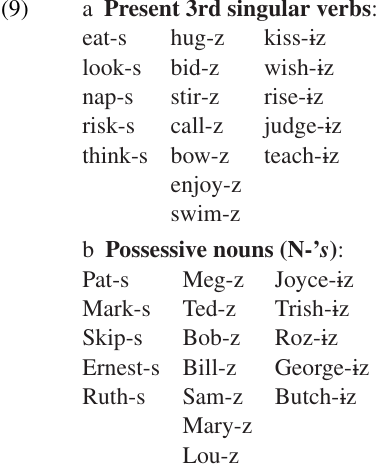

English plural nouns are marked in several different ways, some of which are illustrated in (8). As in (1) and (2), the choice between the variant forms of the plural suffix is phonologically determined. It depends only on the final phoneme of the stem: the form /-ɨz/ occurs after sibilants (grooved fricatives); the voiceless fricative /-s/ occurs after other voiceless consonants; and the voiced fricative /-z/ occurs elsewhere.

But there is an important difference between the pattern in (8) and those in (1) and (2). In (2) there is no phonological similarity at all between the two allomorphs (/-i/ vs. /-ka/). In (1), there is a partial phonological similarity between the two allomorphs (a vs. an); but it seems unlikely that the two can be related by any regular process. The alternation between a and an is unique: there are no other morphemes in modern English in which a final /n/ is always deleted before consonants, or inserted before vowels.1 The alternation in (8), however, is part of a more general pattern. Essentially the same changes are observed in the third person singular agreement suffix (9a) and the possessive clitic (9b).

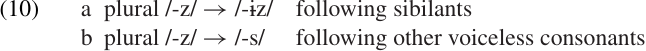

In cases like this, where two (or more) variant forms of a single morpheme are similar in phonological shape and the difference between them follows a regular phonological pattern observed elsewhere in the language, the relationship between the two forms is best analyzed as being morphophonemic. The alternation between two forms is accounted for by a special type of phonological rule, called a MORPHOPHONEMIC RULE. For example, to account for the different forms of the plural morpheme in (8) we could assume that /-z/ is the basic form and formulate morphophonemic rules to derive the other two forms. We will not discuss the details of how to write such rules; for readers who have no previous training in phonology, it may be helpful to consult an introductory phonology textbook.2 But the essence of the rules needed to account for example (8) would be the following:

We have identified the alternations in the regular English plural marker, illustrated in (8), as a morphophonemic process. The alternation in the Korean nominative case marker (2), on the other hand, is clearly not morphophonemic in nature. As we have noted several times, even though the choice between the two allomorphs is phonologically conditioned, there is no phonological similarity between the variant forms (/-i/ vs. /-ka/). There is no plausible phonological process which would change one form into the other. Thus, the Korean alternation seems to be a clear case of suppletive allomorphy.

The contrast between these two cases raises an obvious question: for any given example of phonologically conditioned allomorphy, how can we determine whether the alternation is morphophonemic or suppletive?3 The basic intuition here, to oversimplify somewhat, is that a morphophonemic process replaces one phoneme with another, while a suppletive process replaces one allomorph with another. These two kinds of rules are conceptually very different, and they would play different roles in the overall organization of the grammar. But how can we decide which type of analysis is best in any particular case? Unfortunately, there is no hard and fast answer to this question, but the following criteria will help to guide our decisions.

a NATURALNESS: If the process is phonologically natural, i.e. a process which is found in the phonological systems of many different languages, it is more likely to be morphophonemic. A morphophonemic rule should be phonologically plausible. This criterion alone rules out a morphophonemic analysis of the Korean nominative allomorphy in (2).

b PRODUCTIVITY: If the same process applies to several different morphemes, it is more likely to be morphophonemic. Patterns observed only in a single morpheme are more likely to be suppletive. Returning to the English definite article (1), it would not be implausible to find word-final /-n/ deleted by a phonological rule whenever the following word begins with a consonant. This may well be the historical source of the alternation. However, we argued above that this process is not productive in modern English; the alternation a vs. an is unique. We took this fact as evidence against a morphophonemic analysis, treating it rather as a case of phonologically conditioned suppletion.

c SIMPLICITY: In any area of linguistic analysis, we generally look for the simplest possible grammar which will account for the data. However, it is important to look at the simplicity of the entire rule system, not just of one area (e.g. the phonology). We can always simplify one part of the grammar by adding complex rules to some other part. In the present context, we are interested in comparing two very different kinds of rules. This is not an easy thing to do; but in general, phonological rules are of a simpler type than rules of suppletive allomorphy. Thus, if a plausible morphophonemic analysis is available, the criterion of simplicity would tend to favor that approach over a suppletive analysis.

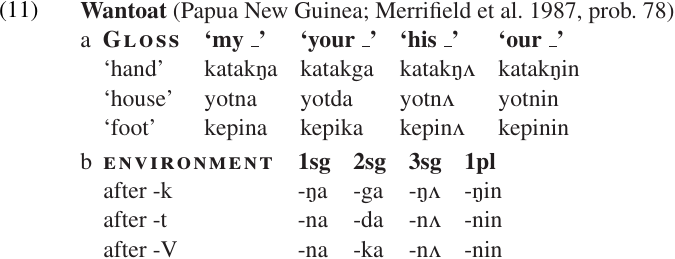

To illustrate how these criteria can be applied, let us consider the Wantoat data in (11a). The allomorphs of the possessive suffixes are summarized in (11b).

Three of these morphemes show exactly the same pattern of allomorphy: initial /ŋ-/ following a velar alternating with initial /n-/ in other environments. If we were to treat this as a case of phonologically conditioned suppletion, we would have to write three separate allomorphic rules, one for each suffix. But it is possible to write just one simple morphophonemic rule which will account for all three alternations:

(12) /n/ → /ŋ/ following a velar consonant

Thus, the morphophonemic analysis is clearly simpler (one rule vs. three rules). The rule in (12) is a case of nasal assimilation, an extremely natural and familiar phonological process. And it is productive in this language, applying to at least three distinct suffixes. Thus, all three of the criteria listed above support the morphophonemic analysis for these morphemes.

The second person possessive suffix, however, is more complicated. Here we have three distinct allomorphs in the three attested environments. Taking the form which occurs following a vowel as the basic form, the phonological changes involved are: (i) /k/ becomes /g/ following a /k/ (voicing dissimilation); and (ii) /k/ becomes /d/ following a /t/ (assimilation in place of articulation plus voicing dissimilation).

Which type of analysis is preferable in this case? Rules of dissimilation, and voicing dissimilation in particular, are found in many languages; but they are much less common than rules of assimilation. Thus, the criterion of naturalness neither rules out nor strongly supports a morphophonemic analysis. The data set is extremely limited, and so offers no evidence regarding productivity (do the same changes occur in other morphemes?). And based on the very limited data available, there is no clear advantage of simplicity for one analysis over the other; either way, we will need two rules to account for the three possible forms. In the absence of additional data, either approach seems possible in this case. But since, as noted above, phonological rules are inherently simpler than rules of allomorphy, a morphophonemic analysis would probably be preferred as a preliminary hypothesis.

1. In earlier forms of English, this kind of alternation did occur in other forms such as my∼mine, thy∼thine. Evidence of this alternation is preserved in poetic forms, e.g. Mine eyes have seen the glory...

2. In particular, the issue of which form to take as the “basic” or underlying form is extremely important; but we cannot address it in the present volume.

3. We can assume, at least for the purposes here, that lexically conditioned allomorphy is always suppletive.

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

الاكثر قراءة في Morphology

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)