Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

The input to the Scottish Vowel Length Rule

المؤلف:

APRIL McMAHON

المصدر:

LEXICAL PHONOLOGY AND THE HISTORY OF ENGLISH

الجزء والصفحة:

P170-C4

2024-12-17

98

The input to the Scottish Vowel Length Rule

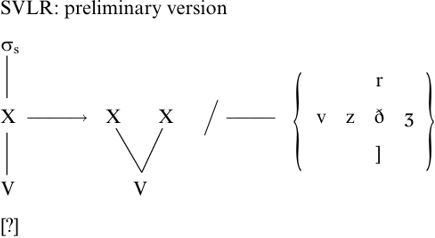

A working version of SVLR was given in vowels, and is repeated. Our main concern here is to replace the question mark in the input of the rule with an informative and motivated feature specification.

(1)

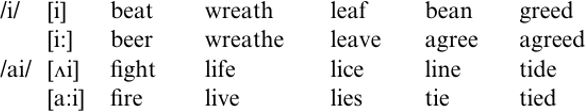

All existing accounts of SVLR agree that it does not apply completely generally. Dialect studies like Dieth (1932), Watson (1923), Wettstein (1942) and Zai (1942) propose monophthongal vowel systems including a set of `vowels of variable quantity' (Zai 1942: 9), which are subject to lengthening before a voiced fricative, /r/ or a boundary, since SVLR lengthening occurs before inflectional suffixes, even when the consonant following the bracket does not itself constitute a lengthening environment; for instance, the stem vowel is long in brewed [bru:d] but short in brood [brud]. Some examples of affected vowels in long and short contexts are given in (2).

(2)

However, the dialect studies also include a subset of /ɪ Λ ε ε̈/ as consistently short vowels, and sometimes a vowel which is always long, like /ø:/ in Morebattle. I shall discuss the long set and the diphthongs first, and then the exceptional short vowels.

The set of `lengthenable' monophthongs comprises /i u e o a ɔ/. Aitken (1981) notes that in some `core' dialects, mainly in the Central Scots area, SVLR operates on all of these; elsewhere, there is a hierarchy of inputs to SVLR, whereby some varieties have only the high vowels /i u/ as lengthenable, others generalize SVLR to mid /e o/, and still others include low /a ɔ/ (Wells 1982, Johnston 1997b). When /a ɔ/ do not lengthen positionally, they tend to be consistently long, and consequently ineligible for SVLR, which as stated in (1), applies to vowels under lyingly associated with only a single X position. The question then is not why these are synchronically exempt from lengthening, but why they were resistant to historical shortening in SVLR short environments; and this is likely to reflect the greater phonetic correlation of length with low vowels (Fischer-Jørgensen 1990).

The diphthongs /Λi/ and /ai/. The other diphthongs of Scots and SSE, /ɔi/ and /Λu/, do not generally undergo SVLR. /ɔi/ is typically consistently long; information on /Λu/ is more variable. Watson (1923) lists word-final lengthened [kΛu:] cow, [yΛu:] ewe, but asserts that the long diphthong is peculiar to Teviotdale, while Zai (1942: 14) observes long [æ:u] `only in the onomatopoeic word mæ:u ``to mew like a cat'''. Lass (1974) explicitly excludes his /au/ from the SVLR, on the grounds that it is extremely marginal in Scots; Johnston (1997b: 497) gives a complete list of /Λu/ words, consisting of coup, loup, howff, nowt, gold, dowse, roll, four, grow, knowe. In many varieties, including Edinburgh Scots (Carr 1992), /Λu/ is consistently short. This diphthong does occur more frequently in SSE, in items with unshifted /u/ in Scots; here /au/ is often consistently long, and may therefore constitute a borrowing from or an assimilation towards RP.

The Modern Scots/SSE descendants of Middle English short high /i u/ likewise fail to undergo the synchronic SVLR. In most Modern Scots dialects, these surface as consistently short [ɪ Λ]; however, the reflexes of earlier /i u/ may vary in quality cross-dialectally - hence Lass's (1974: 336) assertion that `quantity is now in effect neutralized in toto, but not segmentally neutralized for two (synchronically arbitrary but historically principled) vowels'. The `Aitken vowel' /ε̈/, where it appears, is also consistently short.

We now come to the problem of /ε/. Lass (1974), Wells (1982), Aitken (1981), Harris (1985) and Johnston (1997b) all seem to assume that /ε/ forms part of the input for SVLR, but do not discuss it specifically. However, there is in fact little evidence for classifying /ε/ as lengthenable. In earlier dialect studies (Dieth 1932, Wettstein 1942), /ε/ is typically classified as non-lengthening: Grant (1912: §140) alone suggests that /ε/ may lengthen, but only under extremely limited circumstances, namely when it is used `in words spelled air, ere, etc., instead of the old e:'. More recent experimental results are inconclusive: Agutter (1988a, b) did not test /ε/, and McClure (1977) and McKenna (1987), who did, were unable to include a full range of contexts. For instance, the absence of /ε/ from stressed open syllables means that no examples of this vowel word-finally or before inflectional [d] or [z] are available. /ε/ occurs relatively frequently before a consonant cluster with /r/ as the first element, as in heard, herb or serve, but SVLR is strongest before final /r/ (Aitken 1981), and perhaps operates only before final single consonants (although in the absence of conclusive experimental evidence, this must again remain a tentative and corrigible suggestion); and here /ε/ is rare. The pronoun her is unreliable because it is characteristically unstressed and produced with reduced schwa; other cases where /ε/ might be expected, like their, have [e] in Scots/SSE. Even in the few possible forms, like McClure's Kerr /kεr/, a sequence of /ε/ plus an /r/ with any degree of retroflexion would prove almost impossible to segment accurately. Examples of /ε/ before a final voiced fricative (Des /dεz/, rev /rεv/) are only marginally easier to find; but McKenna (personal communication) reports that his subjects experienced some difficulty with rev, so that several of his data points were invalidated. The required contexts seem in some sense unnatural for /ε/. McClure (1977) claims to have found results broadly in line with the length modification expected if SVLR did affect /ε/; but only one informant, McClure himself, was tested, and his average vowel duration and range of durations were considerably higher than those of any speaker tested by Agutter (1988a, b). This makes McClure's findings unreliable, since it is at least possible that they reflect `an exaggerated differentiation of vowel length in long and non-long contexts and extreme carefulness on the part of an informant who knew the purpose of the experiment' (Agutter 1988b: 15). Further experimental work is currently being undertaken, as outlined in Scobbie, Turk and Hewlett (1998), but no results are yet available.

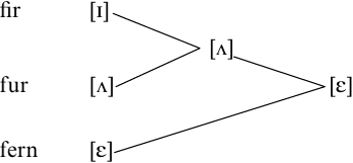

If we accept that /ε/, along with /I n ε̈/, is an exception to SVLR, our next task is to ascertain whether these vowels constitute a natural class, and can be exempted from the rule in a principled way. I propose to use the feature [± tense]: short tense vowels will be eligible for SVLR, but non-lengthening /ɪ Λ ε ε̈/ are [- tense].

This dichotomy can be substantiated on synchronic and diachronic grounds. Synchronically, the evidence is primarily distributional: for instance, tense vowels may characteristically occur in stressed open syllables, and this holds for the [+ tense] Scots/SSE vowels ± bee, blue, bay, bow, law, baa have final /i u e o ɔ a/. However, although bit, but, bet are possible, *[bɪ], *[bΛ], *[bε] are not. /ε/ shows other behavioral and distributional affinities with /ɪ Λ ε̈/, as underlined by Dieth's (1932: 2) description of / ɪ Λ ε ε̈/ as `the phonetician's worry', since they are all interchangeable and hard to distinguish by ear. It is true that in careful speech, or when the items carry prominent or contrastive stress, many Scots speakers differentiate words like fir [fɪɹ], fur [fΛɹ] and fern [fεɹn]; but in more casual registers or under low stress, /ɪ/ and /Λ/ tend to fall together, and /ε/ often joins in too (see (3)).

(3)

In diachronic terms, vowels which undergo SVLR, and those which are consistently and therefore underlyingly long, are precisely those which had some tense sources in Middle English. /i u e o/ have only long/ tense sources, namely post-Great Vowel Shift /i: u: e: o:/ respectively. Short low lax /æ ɒ/ lengthened by historical SVLR while /a: ɔ:/ (which were marginal in Scots after the GVS) shortened, producing mergers: Modern Scots/SSE /a ɔ/ consequently also have some tense sources. /ɪ Λ ε̈/, however, are descended only from lax vowels, and here again /ε/ allies itself with the lax set, since all its possible long/tense sources were collapsed with other vowels during the Great Vowel Shift. Middle English /ε:/ raised to /e:/ and subsequently, in some cases, to /i:/, and although /a:/ in turn raised to /ε:/, it afterwards continued to /e:/, leaving the long half-open front slot empty. Middle English short lax /ε/ might be considered a suitable input to the lengthening subrule of the historical SVLR; but recall that the other short vowels which underwent contextual lengthening, /æ/ and /ɒ/, already had long counterparts in the system: /ε/ alone was isolated.

Giegerich (1992) points out one problem with the characterization of SVLR input vowels as tense: why should the tide, tied vowels be [+ tense], but the other diphthongs [- tense], when in general English diphthongs ally themselves with the long or lengthenable tense monophthongs? There is no real issue here for /ɔi/, which will be tense, but underlyingly long; and the same is true for /au/ in SSE and those Scots varieties where it surfaces consistently long. In cases where it is consistently surface short, I propose the underlier /Λu/, with a lax, unlength enable first element. As for [Λi]/[a:i], recall the proposal that the underlying form for the lengthenable diphthong should be /ai/, contrasting with the pay, way vowel /Λi/, which although restricted to final position, a long SVLR environment, is universally short.

This distinction is not necessary for SSE, where pay, way have /e/ [e:]; but arguably here too, the underlying vowel for the lengthenable diphthong should be /ai/. First, there is some evidence, as we shall see later, for a marginal contrast in SSE too, between short /Λi/ and long /a:i/, since not all speakers maintain the expected SVLR pattern uniformly; the existence of lexical exceptions to SVLR is of some relevance in determining where it applies in the phonology of Modern Scots and SSE. Second, SVLR interacts with the Modern English Vowel Shift Rules. I argued above that the underlying diphthong which surfaces in divine, laxes trisyllabically in divinity and is then eligible for Lax Vowel Shift; the derivation is from /aɪ/ → /a/ → [ɪ]. The assumption that diphthong laxing involves loss of the less prominent element was supported by the reduce ~ reduction alternation, where Lax Vowel Shift was again involved, this time operating on the second element of the rising [ ju] diphthong. If the underlying vowel of divine ~ divinity is /ai/ for Scots and SSE, the Vowel Shift derivation will produce the appropriate surface [ɪ]; but not if the underlier is /Λi/.

I have assumed thus far that the underlying form in the case of alternation is the lexical representation of the underived form; and this would mean /Λi/. There may, however, be one set of circumstances where we have to allow deviation from this general requirement, namely where there is a partial surface merger of two underlyingly distinct segments. In this case, proposing the surface form of the underived member as the underlier would suggest, counterfactually, that the merger was a full phonological one. The classic case here would be final devoicing in German, where the underived surface forms have voiceless stops, and the related but morphologically derived ones have voicing. But if we select voiceless stops as underlying, there is a conflict, since there are other, non-alternating morphemes which have invariant voiceless stops. There are then good phonological arguments for assigning underlying voiceless stops to the latter set, and voiced ones to the alternating forms. The Scots case is parallel to the German one, in that pay, way have unlengthenable [Λi], which should surely preferentially be assigned underlying /Λi/; if we are not to predict that the tied vowel is also quantitatively invariant, we must then prefer /ai/, the lexical representation of the derived alternant.

This argument does not hold in precisely the same way for SSE, where as we have seen, pay and way are not diphthongal; but it will go through if there is an incipient split of underlying /Λi/ (which is axiomatically unlengthenable) and /ai/, as I shall argue later. In that case, /Λ/, whether monophthongal or part of a diphthong, is a good diagnostic of failure to lengthen; and SVLR can straightforwardly be stated as a lengthening rule. We still have the problem of deriving [Λi] in SVLR short contexts which, as Carr (1992) points out, is a difficulty for all current analyses of SVLR. My proposal that SVLR initially affected only monophthongs, and that the [Λi] ~ [a:i] alternation was later incorporated into it, complete with a pre-existing quality difference reflecting earlier and later GVS reflexes of original /i:/, at least puts the synchronic mismatch of diphthong and monophthongs into historical perspective.

The use of [+ tense] in the structural description of SVLR will, then, effect the appropriate exclusions, and is clearly synchronically and diachronically motivated, insofar as the feature [± tense] itself is motivated. However, as Halle (1977: 611) notes, `the feature of tenseness has had a long and complicated career in phonetics', and its integrity and usefulness have been challenged. A short excursus to justify the use of [± tense] is therefore necessary; my contention that Lexical Phonology can capture necessary and relevant generalizations without undue abstractness will hardly benefit from avowed support for a `pseudo feature' (Lass 1976).

Lass (1976) bases his case for the abandonment of [± tense] largely on the fact that its measurable phonetic correlates are typically `based on the presumed ``effects'' of tenseness. And all of these ``effects'' are independent variables, parameters that require independent notation in any case' (Lass 1976: 40). That is, when two vowels differ with respect to a cluster of phonetic factors such as relative height, backness and degree of rounding, each factor should be considered separately rather than ascribed as a set to `an explanatory abstraction' (Lass 1976: 49) like tenseness. However, Halle (1977: 611), Giegerich (1992: 98) and Anderson (1984) all acknowledge the multiple correlations of tenseness with other features, but nonetheless maintain that [± tense] is necessary for classificatory reasons. As Anderson (1984: 95) puts it, `there is a considerable amount of disagreement in the phonetic literature concerning the precise definition of this distinction. There is rather less disagreement, however, on the proposition that there is indeed something to be defined.'

In fact, Lass's arguments for the dismissal of [± tense] as a `pseudo feature' can be countered. First, [± tense] does, in fact, have verifiable phonetic correlates, as shown by Wood (1975). Wood used X-ray tracings of vowel articulations to demonstrate that tense and lax vowels differ consistently in degree of constriction and, less importantly, in pharyngeal volume. Furthermore, tense rounded vowels tended to show a greater degree of lip-rounding than the corresponding lax vowels. Wood's results from English, German, Egyptian Arabic, Southern Swedish and West Greenlandic Eskimo indicate that `the articulatory gestures involved appear to be much the same irrespective of language, which points to a universal physiological and biological basis for the acoustical contrasts founded on [the tense-lax AMSM] difference' (1975: 111). Fischer-Jørgensen (1990) provides a critique of Wood's experimental method, which involved enlarging X-ray photographs from the phonetic literature and measuring tongue constriction and jaw opening from these; this is potentially problematic, in that the available material is somewhat restricted, and may not all be equally valid, or have been collected under sufficiently similar conditions. Nonetheless, Fischer Jørgensen (1990: 106) concludes that Wood's sources are sound for American English and German at least, and that `in spite of the restricted and somewhat uneven material the results seem to be pretty clear and reliable'. Moreover, Fischer-Jørgensen establishes that `the tense-lax characteristic is supported by EMG measurements' (1990: 107), with tense vowels involving greater activity of the genioglossus muscle, and possibly also the inferior longitudinal muscle and the geniohyoid. Lax vowels in Fischer-Jørgensen's studies of American English and German also had higher F1 (correlating with lower tongue height) and higher F2 than their tense counterparts, as well as relatively high F0, which Fischer Jørgensen (1990: 131) establishes cannot be due purely to the shorter duration of the lax vowels.

Carr (1992: 96), considering Wood's results, counters that `there is a difference between correlates and definitions. No-one doubts the phonetic reality of the properties we take to be the correlates which we associate with ``tenseness''. But clearly, demonstrating the reality of the correlates is not equivalent to defining the feature.'

I suspect I hear the grating of goalposts being moved here: but this phonological argument can also be answered. It is true that tenseness is intimately connected with tongue height, frontness/backness and degree of lip rounding, which can be individually described using independent features. However, the importance of these components for the tense-lax dichotomy lies not in their individual contributions, but in their conjunction; and the weighting of contributory features is not equivalent for different tense-lax pairs. So, although tense vowels tend uniformly to be more peripheral than their lax counterparts (Lindau 1978), the interpretation of `peripherality' is fluid: a high front tense vowel will be higher and fronter than its lax counterpart, while a low back rounded tense vowel will be lower, more back, and more rounded. It is this variable clustering of features, which would be difficult to relate using only the contributory elements, that [± tense] is intended to encapsulate. This makes [± tense] extremely useful; as Giegerich (1992: 98) points out, `the phonological classification of the English vowel system would without the use of this feature be an extremely difficult task'. It also, undeniably, makes [± tense] a phonological feature, and hence phonetically relatively abstract: Anderson (1981: 496) argues persuasively for the recognition of just such features, `for which the evidence is sometimes (or perhaps always) indirect or inferential rather than observational'.

Having established that [± tense] does have measureable though variable phonetic markers, we must ascertain how the aggregation of these markers into a single grouping of tense versus lax is phonologically beneficial. It certainly appears that the use of [± tense] may make otherwise opaque natural processes explicable and characterizable; see the analysis of MEOSL in Lieber (1979). This is surely one of the major tasks of linguistics and a primary requirement of the formal and theoretical tools it employs. Lass also asserts that tenseness is definable only according to its effects (such as the presence of glides, in SPE terms), rather than `on the basis of a prior (historically based) partitioning of the lexicon' (1976: 40): but we have already seen that a `historically based' characterization can readily be found for the four lax vowels /ɪ Λ ε ε̈/ in Modern Scots/SSE, which form a historically motivated natural class as the only vowels in the inventory with no long (or tense) Middle English sources. These cannot be classified simply as short, since most, if not all Scots vowels are underlyingly short, but this group also fail to undergo SVLR.

Indicating the various ways in which `tense' vowels differ from `lax' ones individually, without subsuming these parameters under a unifying feature of tenseness, can therefore be shown to be intrinsically unsatisfactory for some languages. In particular, Wood rejects the possibility of deriving tenseness universally from length on the grounds that `the relationship between tenseness and quantity can vary synchronically from language to language and diachronically from period to period in one and the same language' (Wood 1975: 110). Thus, while in at least some varieties of Modern English tenseness is predictable from length, both long and short vowels may be tense in Icelandic (Anderson 1984: 95-6). Recent work by Labov (1981) and Harris (1989), to be reviewed below, suggests that the æ-Tensing rule operative in varieties like Philadelphia, New York City and Belfast has led to underlying restructuring in some dialects, producing a distinction of short lax /æ/ and short tense /Æ/. This brings us to the frequent observation (Carr 1992, Giegerich 1992) that the tense-lax distinction is not so well motivated for low vowels as for higher ones. But [± tense] would hardly be the first feature to have a skewed distribution across different classes of segments: for instance, voicing is typically not contrastive for sonorants, while higher front rounded vowels are significantly more common than lower ones. What we may be seeing in the case of low vowels is the interference of two factors: the greater phonetic likelihood of lengthening in low vowels, and the fact that length is typically, though not universally, a sign of tenseness.

In diachronic terms, I have argued that in Middle English long vowels are consistently tense and vice versa; the advent of SVLR has disrupted this correlation for Scots/SSE, where tense vowels are now those which may become long, under certain phonetic circumstances. This position is not uncontroversial: for instance, Lass (1980) proposes, on the basis of evidence from John Hart's Orthographie, that laxing and lowering of Middle English /i e u o/ did not take place until the seventeenth century. Laxing of short vowels would then follow or overlap with the historical SVLR. However, Lass's dating can be questioned. His assumption is that, since Hart does not mention a qualitative distinction between long and short vowels, no such difference existed in the mid-sixteenth century: but as Lass also admits (1980: 85) that Hart `does not discriminate tongue-height as an independent variable', Hart's failure to distinguish (lower) lax vowels from (higher) tense ones may reflect a failing of his descriptive system rather than providing evidence of late laxing.

Returning to the SVLR, there is one final `how else?' argument for tenseness: if we do not classify the SVLR input vowels as [+ tense], what do we call them? Carr (1992: 109), in a Dependency Phonology analysis, makes three suggestions. First, vowels with the centrality component {ə} (namely /ɪ Λ ε Λu/) do not lengthen, although Carr himself notes that his assignment of {ə} is questionable, because of the [Λi] ~ [a:i] alternation, and the pervasive Scots and SSE centralization of /i/ and especially /u/. Secondly, invariably long vowels are exempt from SVLR, a point accepted above and independent of Carr's Dependency Phonology model. Finally, Carr (1992: 109) argues that `the ``color'' elements {i} and {u} seem crucial in determining participation in SVLR'; if /i u e o/ are the lengthenable vowels, then `simple preponderance of these elements will suffice to characterize the input set'. Carr (1992: 111) contends that this use of the color elements is preferable to [‹ tense] because SVLR in some varieties applies to only /i u/, `and these cannot be picked out independently of /e/ and /o/ with the characterization [+ tense]'. But Carr's own account of the SVLR vowels as those where {i} and {u} are dominant will not pick out /i u/ alone either; he will have to specify that in the relevant varieties, lengthenable vowels are those composed solely of a color element. In addition, for varieties where the low vowels undergo SVLR, since /a ɔ/ are in Dependency Phonology terms {a} and {a;u}, Carr cannot rely on the color elements, and instead has to assume that single or dominant {a} also conditions lengthening.

There are two questions here: why is the use of the color elements {i}, {u} and possibly {a} an improvement on a hierarchy of lengthenability depending on vowel height; and why should the colour elements in particular be involved? In fact, the two systems of notation seem equivalent, both expressing the greater likelihood of SVLR lengthening for higher vowels. However, there is a problem for Dependency Phonology here, since there is not generally a strong correlation of greater height with greater length: in fact, the reverse is the case (and note that, when the low vowels are exempt from SVLR, they are consistently long). The better correlation here, as Wood (1975) and Fischer-Jørgensen (1990) point out, is between height and tenseness, the latter in turn being signalled very frequently by greater length. Carr notes that Ewen and van der Hulst (1988) take {i} and {u} to constitute |Y|, a tongue-body constriction sub-feature, and concedes (1992: 111) that `there may be some mapping between Ewen & van der Hulst's sub-feature and the feature [tense]'. The independence of these two accounts, and the rejection of tenseness, must surely be called into doubt. I therefore replace the question mark of (1) with the specification [+ tense] in (4); in different varieties, this may need to be supplemented with a height specification.

(4)