Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Identifying Improper Class Groupings

المؤلف:

BARBARA MINTO

المصدر:

THE MINTO PYRAMID PRINCIPLE

الجزء والصفحة:

91-6

2024-09-14

479

Identifying Improper Class Groupings

Identifying the proper source of a supposed class grouping can be a terrific aid in helping you clarify your real message. Suppose you came across this:

The traditional financial focus of investment evaluation results in misleading prescriptions for corporate behavior:

1. Corporations should invest in all opportunities where probable returns exceed the cost of capital

2. Better quantification of future uncertainty and risk is the key to more effective resource allocation

3. Planning and capital budgeting are two separate processes -Capital budgeting is a financial activity

4. Top management's role is to challenge the numbers rather than the underlying thinking

Now apparently these four "misleading prescriptions" reflect commonly believed "rules of thumb" in corporations. But do they? If you reword them as results, they say, in abbreviated form:

The financial focus:

1. Encourages corporations to invest

2. Emphasizes quantification of uncertainty

3. Separates planning and capital budgeting

4. Leads top management to focus on the numbers

All but the third can now be seen as part of a process of decision making, which would dictate time order which in turn would lead to a clearer point at the top:

The traditional financial focus of investment evaluation can result in poor resource allocation decisions because it:

l. Emphasizes quantification of future uncertainty and risk as the key to choosing among projects

2. Leads top management to focus on the numbers rather than on the underlying thinking

3. Encourages investment in all opportunities where probable returns exceed the cost of capital, ignoring other considerations

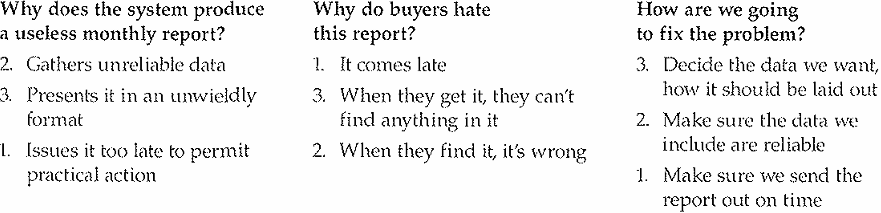

That one was easy to sort out because the kind of idea you were dealing with was easy to identify simply by reading it. Very often, however you will find yourself with a longer list of ideas classified as “reasons" or "problems", obscuring the fact that it contains subclasses of varying kinds of reasons or problems. Remember this example from the introduction to this section:

Buyers are unhappy with the sales and inventory systems reports

1. Report frequency is inappropriate

2. Inventory data are unreliable

3. Inventory data are too late

4. Inventory data cannot be matched to sales data

5. They want reports with better formats

6. They want elimination of meaningless data

7. They want exception highlighting

8. They want to do fewer calculations manually

The trick is to go through and sort them into rough categories, as a prelude to looking more critically. You get the categories by defining the kind of problem being discussed in each case. Thus, if "Report frequency is inappropriate," the type of problem indicated is "Bad timing," etc.

Now you see that the author is complaining about three types of problem with the reports: timing, data, and format. What order do they go in? That depends on whether you are talking about the process of preparing the report, the process of reading the report, or the process to follow in fixing the problem. In other words, the order reflects the process, and the process is dependent on the question being answered:

This example has demonstrated the only process I know for getting at the real thinking underlying lists of ideas grouped as a class.

1. Identify the type of point being made

2. Croup together those of the same type

3. Look for the order the set of groups implies.

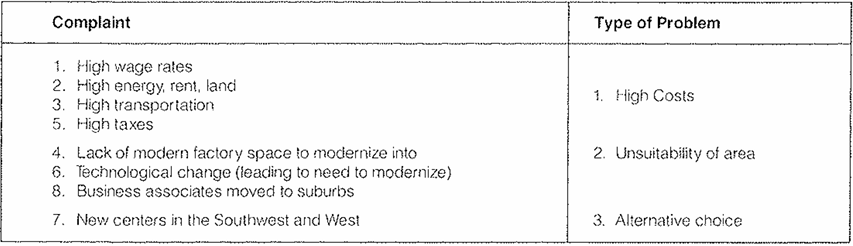

Here is another example of the process in application:

The causes of New York's decline are many and complex. Among them are:

I. Wage rates higher than those that prevail elsewhere in the country

2. High energy, rent and land costs

3. Traffic congestion that forces up transportation costs

4. A lack of modern factory space

5. High taxes

6. Technological change

7. The competition of new centers of economic concentration in the Southwest and West

8. The refocusing of American economic and social life in the suburbs

Again, this is just a list rather than a communication of thinking. But the process for getting at the underlying thinking does work. First, look for similarities.

Then look for order and the message. In this case it is probably order of importance:

The causes of New York's decline are easy to trace

1. High costs

2. Difficult working conditions

3. Attractive alternatives

To summarize, I have tried to demonstrate with all these examples that checking order is a key means of checking the validity of a grouping. With any grouping of inductive ideas that you are reviewing for sense, always begin by running your eye quickly down the list. Do you find an order (time, structure, degree)? If not, can you identify the source of the grouping and thus impose one (process, structure, class)? If you have a long list, can you see similarities that allow you to make subgroupings, and impose an order on those?

Once you know a grouping of ideas is valid and complete, you are in a position to draw a logical inference from it, as explained in: Summarizing Grouped Ideas.

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى) قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر مجموعة قصصية بعنوان (قلوب بلا مأوى)