Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

When to Use it

المؤلف:

BARBARA MINTO

المصدر:

THE MINTO PYRAMID PRINCIPLE

الجزء والصفحة:

64-5

2024-09-12

1094

When to Use it

This slow-moving approach leads me to urge that, on the Key Line level, you try to avoid using a deductive argument, and strive instead always to present your message inductively. Why? Because it is easier on the reader.

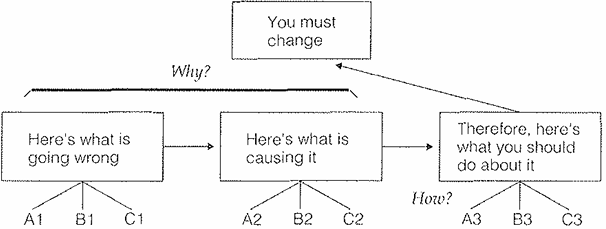

Let's look at what you force the reader to do when you ask him to absorb a deductively organized report. Suppose you wish to tell him that he must change in some way. Your argument would look something like this:

To absorb your reasoning, the reader must first take in and hold the A-B-Cs of what is going wrong. I agree this is not a difficult task, but then you ask him to take the first A of what is going wrong, bring it over and relate it to the second A of what is causing it, and then hold that in his head while you make the same match for the Bs and Cs. Next you ask him to repeat the process, this time tying the first A of what is going wrong to the second A of what is causing it, and hauling the whole cart load to hitch to the third A of what to do about it. And the same with the Bs and Cs.

Not only do you make the reader wait a very long time to find out what he should do Monday morning, you also force him to reenact your entire problem-solving process before he receives his reward. It is almost as if you're saying to him, "l worked extremely hard to get this answer and I'm going to make sure you know it." How much easier on everybody were you simply to present the same message inductively:

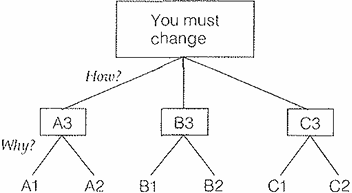

Here, instead of answering the "Why?" question first and the "How?" question second, you simply reverse the order: And now, while you may indeed have deductive arguments at the lower levels, still you have answered the reader's major question directly, with clear fences in your thinking between subject areas, and all information on each subject in one place.

But isn't deductive reasoning stronger and tighter than inductive, people usually ask me. Not at all. It is all the same reasoning; we are only discussing how to lay it out on the page.

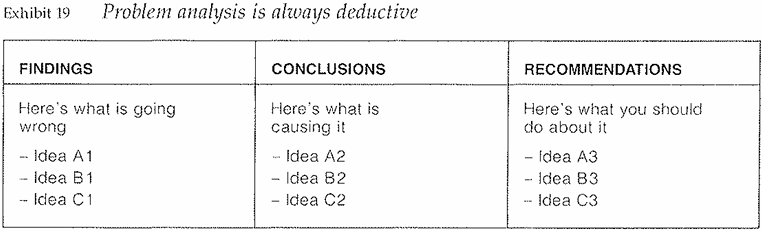

To explain it another way, at the end of the problem-solving process you will have come up with a set of ideas that can be sorted onto a Recommendation Worksheet like that shown in Exhibit l9. The worksheet permits you to visualize the fact that you have gathered findings that led you to draw conclusions from which you determined recommendations.

These designations-findings, conclusions, recommendations-though widely used, are actually something of a misnomer. There is in fact no difference between a finding and a conclusion, other than a rather arbitrary labeling of level of abstraction. The summary of a group of findings is always a conclusion. Thus, you will have a set of findings and conclusions to support what is going wrong, and another set to support what is causing it.

In order to have come to these clusters of conclusions, you will have had to use three types of reasoning: induction, deduction (both of which you know about), and abduction. Abduction, as you can see in Appendix A, Problem Solving in Structureless Situations, occurs when you make a hypothesis and look for information to support it. But of course once you have the information, the reasoning becomes induction.

Your reasoning as laid out in the worksheet is complete-the only decision is how to present it. If you want to present the message deductively, you lay it out one column at a time, as shown on the previous page. If you want to present it inductively, you simply turn the whole thing 90 degrees to the left and put the recommendations on the Key Line, with the appropriate finding/conclusion grouped underneath.

The issue here is whether it is better to tell the reader why he should change and then how to go about it, or that he should change and why each change makes sense. As a rule of thumb, it is always better to present the action before the argument, since that is what the reader cares about, unless you face one of those rare cases in which it is the argument he really cares about.

When might the argument for any action be more important to the reader than the actions themselves? When the point you are making at the top of the pyramid is alien to the kind of thing he expects you to say. For example, imagine the following dialogues:

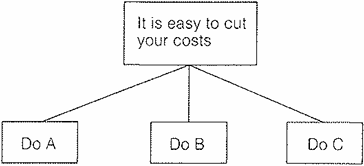

Situation 1

Him Tell me how to cut my costs

You It is very easy to cut your costs

Him How?

You Do A, do B, do C

Obviously here we would want a standard inductive pyramid.

Situation 2

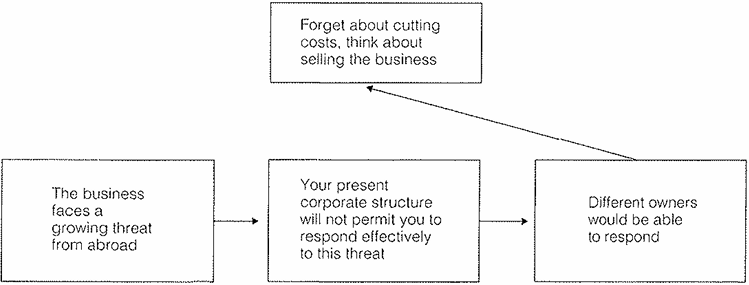

Him Tell me how to cut my costs

You Forget about cutting costs, you should be thinking about selling this business

Him Why? How? Are you sure? Good God'

Here you clearly need a deductive argument.

The only other time I can think of when you automatically know you need a deductive argument at the Key Line level is when the reader is incapable of understanding the action without prior explanation, as in David Hertz's article on how to do risk analysis that we looked at earlier. Here the reader needed to know the reasoning that underlies the analytical approach before he could understand the actual steps in the approach.

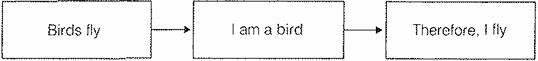

Few of the recipients of business documents fall into either class, however, so that in general you will find yourself wanting to structure the Key Line of your pyramid to form an inductive argument. Note that I am talking only about the Key Line here, and not about lower levels. Deductive arguments are very easy to absorb if they reach you directly:

When, however, you must plough through 10 or 12 pages between the first point and the second, and between the second and the third, then they lose their instant clarity. Consequently, you want to push deductive reasoning as low in the pyramid as possible, to limit intervening information to the minimum. At the paragraph level deductive arguments are lovely; and present an easy-to-follow flow; but inductive reasoning is always easier to absorb at higher levels.

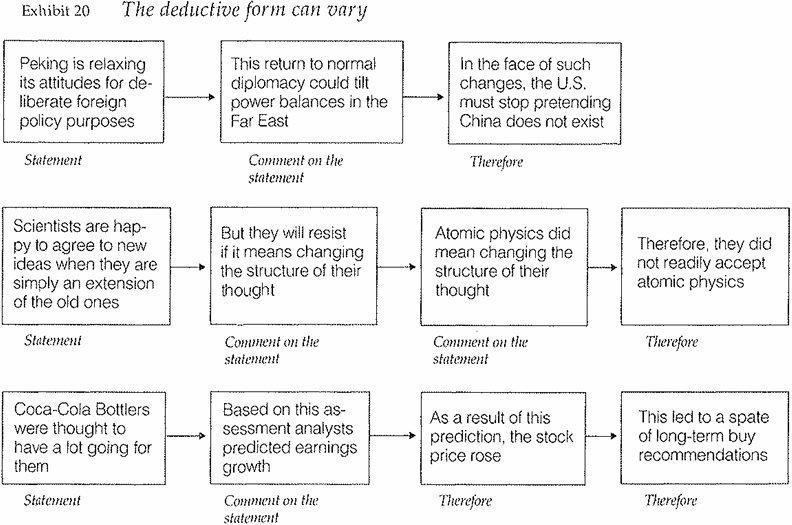

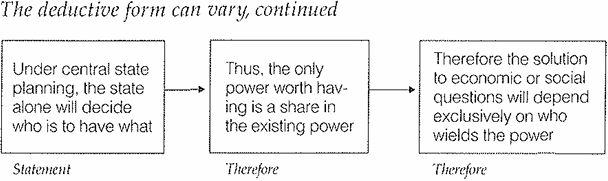

If you do decide to use deductive reasoning at the lower levels of your pyramid, there are some permissible types of chained argument, beyond the basic syllogistic form, of which you should be aware (Exhibit 20).

The only rules to bear in mind in chaining deductive arguments are that (a) you cannot have more than four points in a deductive argument, and (b) you cannot chain together more than two "therefore" points. Actually, you can do both if you want to (the French philosophers do so all the time), but the groupings will be too heavy to summarize effectively. So if you wish to make proper summaries, you must limit your deductive groupings to no more than four points.

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)