Do I Need to Introduce the Key line Points?

Each of the Key Line points should also be introduced, following roughly the same S-C-Q process that you used to write the initial introduction, although much more briefly. That is, you again want to tell your reader a brief story that will ensure he is standing in the same place you are as he asks the question raised by stating each Key Line point.

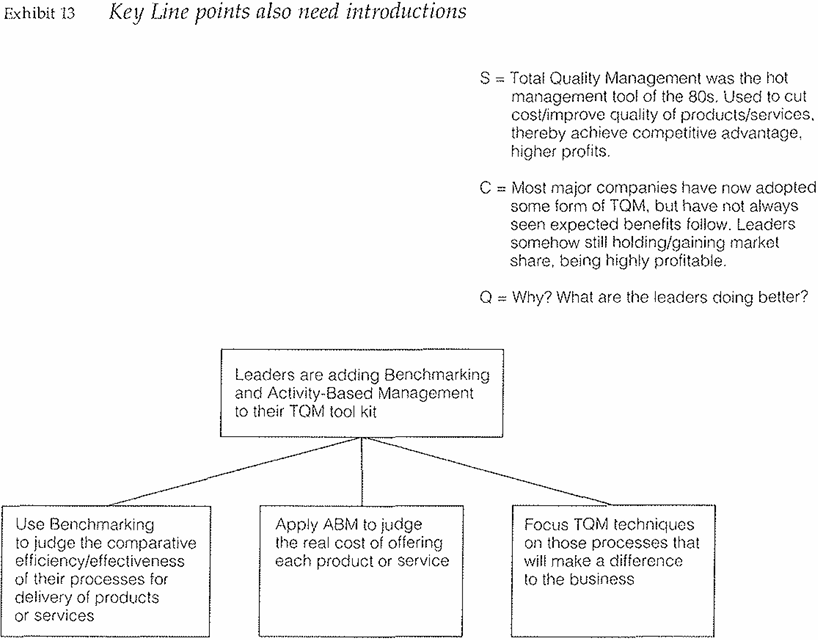

To illustrate, look at Exhibit 13, which shows the structure of a paper on "Management Tools for the Nineties".

The initial introduction has the form:

S = The belief is that using X tool will give you Y

C = Are using X, but others getting Y

Q = Why are others getting Y?

A = Using A + B + X

The answer leads directly to the new question, "How does using those things get to Y (competitive advantage, higher profits)?" and to Key Line points that say that leading companies:

- Use Benchmarking to judge the comparative efficiency/effectiveness of their products or services

- Apply Activity-Based Management to judge the real cost of offering each product or service

- Focus TQM techniques on those processes that will make a difference to the business.

The question under each point is "How does that work?", and the plural noun is "steps". However, you cannot simply begin writing by stating each point and then supporting it. You need to mark its place on the page with a heading that reflects the essence of the point to follow; and then introduce the point. Thus you would not say:

BENCHMARKING

Leaders use benchmarking to judge the comparative efficiency and effectiveness of their processes for delivering products or services. To do so, they:

- Measure efficiency of key processes

- Compare performance against competitors

- Identify underlying reasons for differences.

Rather, you want to use a heading that reflects more clearly the essence of the point. And you want to lead up to the point by reviewing for the reader what he already knows about the subject (benchmarking), and how a question would have arisen to which this point is the answer. For example:

BENCHMARKING PROCESS EFFICIENCY

S = Suppose you have put in TQM and cut loan application processing time from 2 days to 2 hours.

C = Are likely to assume such a big reduction is enough for competitive advantage

Q = Is it enough?

A = You can't tell until you compare yourself with the competition.

Introductions for the other Key Line points follow the same pattern.

DETERMINING REAL COSTS

S = Let's say you have now fully benchmarked yourself and become the best, so that everybody measures himself against you

C = Have every right to be proud, provided the actual return from offering the product/service is worth the real cost to produce/supply it

Q = How do you determine that what you are the best at is worth doing?

A = Analyze costs by activity rather than by function (Activity-Based Management)

ADJUSTING TQM TECHNIQUES

S = Have now gone out and benchmarked, applied ABM. Know where your processes are weak compared to competition, which products/services are really costly or wonderfully profitable

C = Time now to start tightening up those processes

Q = Is this where we use TQM?

A = Yes, but now will be using TQM activities primarily on those processes that will make a significant difference to the business

The difference between the initial and subsequent introductions lies in where the reader happens to be standing as he reads each. At the time of the initial introduction, you write to remind him what he knows about the subject of the paper (current management techniques). At the first Key Line point you write to remind him why this subject is relevant to the overall point. At the other Key Line points, you write to show him how the about-to-be-discussed subject is relevant to the one previously discussed.

In other words, you make yourself aware of what has immediately been put into the reader's head, and thus (given his vantage point) what else he needs to be told to elicit the question to which your next point is the answer.

To emphasize the theory behind writing good introductions:

1. Introductions are meant to remind rather than to inform. This means that nothing should be included that would have to be proved to the reader for him to accept the statement of your points-i.e., no exhibits.

2. The introduction should always contain in the three elements of a story. These are the Situation, the Complication, and the Solution. And in longer documents you will want to add an explanation of what is to come. The first three elements need not always be placed in classic narrative order, but they do always need to be included, and they should be woven into story form.

3. The Length of the introduction depends on the needs of the reader and the demands of the subject. Thus, there is scope to include whatever is necessary for full understanding: history or background of the problem, outline of your involvement in it, any earlier investigations you or others have made and their conclusions, definitions of terms, and statements of admission. All these items can and should be woven into the story however.

What must be apparent by now from these examples is that the pivot on which your entire document depends is the beginning Question, of which there is always only one to a document. If you have two questions, they must be related: "Should we enter the market, and if so, how?" is really "How should we enter the market?" since if the answer to the first part is no, the second part does not arise. And if the answer to the first part is yes, that becomes the point at the top of the pyramid, raising the question "How?" which gets answered on the Key Line.

On occasion you will not be able to determine the question easily just by thinking through the introduction. In that case, look at the material you intend to include in the body. Whenever you have a set of points you want to make, you want to make them because you think the reader should know them. Why should he know them? Only because they answer a question. Why would that question have arisen? Because of his situation. So that by working backward you can invent a plausible introduction to give your question a logical provenance.

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة