THE VERTICAL RELATIONSHIP

المؤلف:

BARBARA MINTO

المؤلف:

BARBARA MINTO

المصدر:

THE MINTO PYRAMID PRINCIPLE

المصدر:

THE MINTO PYRAMID PRINCIPLE

الجزء والصفحة:

13-2

الجزء والصفحة:

13-2

2024-09-04

2024-09-04

1056

1056

THE VERTICAL RELATIONSHIP

Some of the most obvious facts in the world take years to work their way into people's minds. A good example is what happens when you read. Normal prose is written one-dimensionally, in that it presents one sentence after another, more or less vertically down the page. But that vertical follow-on obscures the fact that the ideas occur at various levels of abstraction. Thus, any idea below the main point will always have both a vertical and a horizontal relationship to the other ideas in the document.

The vertical relationship serves marvelously to help capture the reader's attention. It permits you to set up a question/answer dialogue that will pull him with great interest through your reasoning. Why can we be so sure the reader will be interested? Because he will be forced to respond logically to your ideas.

What you put into each box in the pyramid structure is an idea. I define an idea as a statement that raises a question in the reader's mind because you are telling him something he does not know. (Since people do not generally read to find out what they already know, it is fair to state that your primary purpose in communicating your thinking will always be to tell people what they do not know.)

Making a statement to a reader that tells him something he does not know will automatically raise a logical question in his mind-for example, Why? or How? or Why do you say that? You as the writer are now obliged to answer that question horizontally on the line below. In your answer, however, you will still be telling the reader things he does not know, so you will raise further questions that must again be answered on the line below.

You will continue to write, raising and answering questions, until you reach a point at which you judge the reader will have no more logical questions. (The reader will not necessarily agree with a writer's reasoning when he's reached this point, but he will have followed it clearly, which is the best any writer can hope for.) The writer is now free to leave the first leg of the pyramid and go back up to the Key Line to continue answering the original question raised by the point in the top box.

The way to ensure total reader attention, therefore, is to refrain from raising any questions in the reader's mind before you are ready to answer them. Or from answering questions before you have raised them. For example, any time a document presents a section captioned "Our Assumptions" before it gives the major points, you can be sure the writer is answering questions the reader could not possibly have had an opportunity to raise. Consequently; the information will have to be repeated (or reread) at the relevant point in the dialogue.

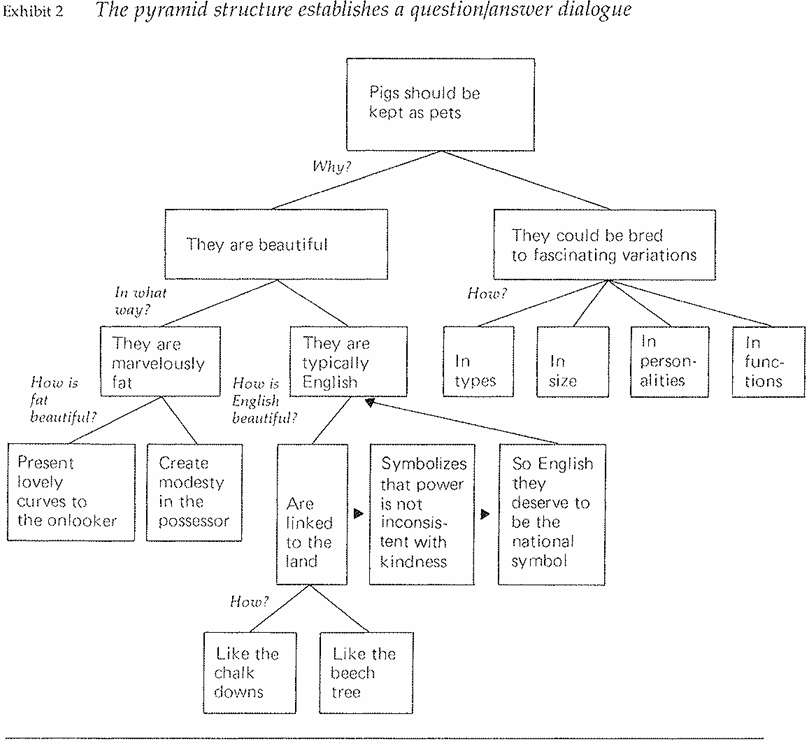

The pyramid structure almost magically forces you to present information only as the reader needs it. Let me take you through a couple of examples. Exhibit 2 displays a humorous one, from an article by G.K. Chesterton. I chose it because it will give you an idea of how the vertical question/answer technique works to hold the reader's attention without burdening you with the need to think about the horizontal logic of the content.

Chesterton says that pigs should be kept as pets; the reader asks Why? Chesterton says, "For two reasons: First, they are extremely beautiful, and second, they could be bred to fascinating variations."

Reader: What makes you say pigs are beautiful?

Chesterton: They're beautiful because they're marvelously fat and they're typically English.

Reader: What's beautiful about being fat?

Chesterton: It presents lovely curves to the onlooker and it creates modesty in the possessor.

Now at this point, while you clearly do not agree with Chesterton's argument, you can at least see what it is. It is clear to you why he says what he says, and there are no further questions required to reveal his reasoning. Consequently, he can move on to the next leg of his argument-that pigs are beautiful because they are typically English.

Reader: Why is typically English beautiful?

Chesterton: Pigs are linked to the land; this link symbolizes that power is not inconsistent with kindness; that attitude is so English and so beautiful that they deserve to be the national symbol.

Again, you may have a certain prejudice against the sentiment, but it is clear to you why he says what he says. And it is clear because the grouping of ideas sticks to doing its job of answering the question raised by the point above. The last section, about variations, enters the mind equally clearly.

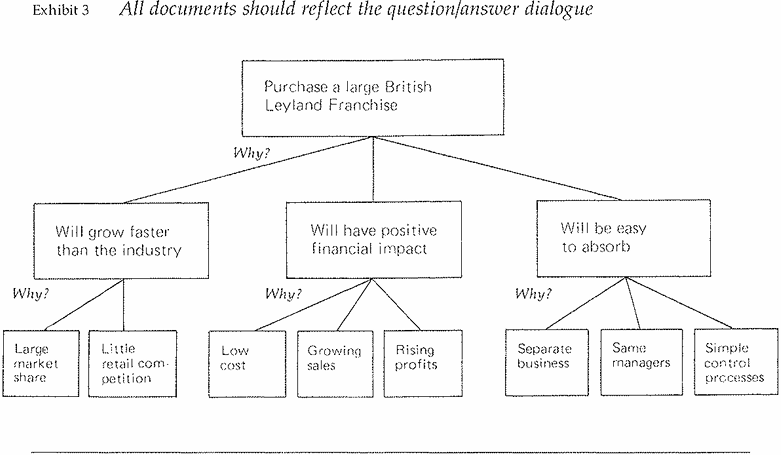

You can see this same technique at work in a piece of business writing (Exhibit 3). Here we have the structure of a 20-page memorandum recommending the purchase of a British Leyland franchise (several years ago, obviously). It is a good buy for three reasons, and underneath each reason is the answer to the further question raised in the reader's mind by making this point. The reasoning is so clearly stated that the reader is in a position to determine whether he disagrees with the writer's reasoning, and to raise logical questions concerning it.

To summarize, then, a great value of the pyramid structure is that it forces visual recognition of the vertical question/answer relationship on you as you work out your thinking. Any point you make must raise a question in the reader's mind, which you must answer horizontally.

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

الاكثر قراءة في Writing

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة