x

هدف البحث

بحث في العناوين

بحث في المحتوى

بحث في اسماء الكتب

بحث في اسماء المؤلفين

اختر القسم

موافق

Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Past Simple

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Passive and Active

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Grammar Rules

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Semantics

Pragmatics

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

literature

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

EPP in other infinitives

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

313-8

31-1-2023

744

We posited that raising to does not carry an [EPP] feature. This would mean that a sentence such as (71a) below has the skeletal structure (71b), with he originating as the thematic subject of admire and being raised directly to become the structural subject of does (as shown by the dotted arrow):

More specifically, we assumed that to in raising structures like (71b) does not have an [EPP] feature, so that he does not become the subject of to at any stage of derivation. If to in raising clauses is assumed to be defective (and hence to lack person and/or number  -features), this is entirely consistent with Chomsky’s suggested generalization that only a

-features), this is entirely consistent with Chomsky’s suggested generalization that only a  -complete T carries an [EPP] feature.

-complete T carries an [EPP] feature.

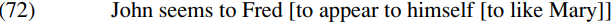

However, Chomsky (2001, fn. 56) argues that (somewhat contrived) sentences like (72) below provide empirical evidence that raising to does after all have an [EPP] feature:

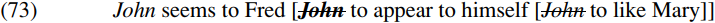

Here, himself refers to John, not to Fred. This is puzzling if we assume that the antecedent of a reflexive must be an argument locally c-commanding the reflexive (and hence contained within the same TP as the reflexive), since if raising to has no [EPP] feature and John moves directly from being the subject of the like clause to becoming the subject of the seem clause, the lefthand bracketed TP containing the reflexive will contain no antecedent for himself, and hence we will wrongly predict that sentences like (72) are ill-formed. By contrast, argues Chomsky, if we posit that raising to does indeed have an [EPP] feature, John will move from being subject of like Mary to becoming subject of to like Mary, then later becoming subject of to appear to himself to like Mary, before finally moving to become the subject of the null T constituent in the seem clause. This will mean that a null trace copy of John is left behind as the subject of each of the two infinitive clauses, as shown in skeletal form in (73) below:

Since the reflexive himself is locally c-commanded by the bold-printed trace John in (73) within the lefthand bracketed TP containing the reflexive, (73) correctly predicts that himself will be interpreted as referring to John. (Recall that Chomsky posits that traces are deleted in the phonological component but remain visible in the syntactic and semantic components.) Further evidence that A-movement in raising structures is successive-cyclic is presented in Boˇskovi´c (2002b).

Sentences like (73) suggest that raising to must have an [EPP] feature triggering movement of an argument to spec-TP. But it’s important to bear in mind that the [EPP] feature on T works in conjunction with the person/number  -features of T: more specifically, the [EPP] feature on T triggers movement to spec-TP of an expression which matches one or more of the

-features of T: more specifically, the [EPP] feature on T triggers movement to spec-TP of an expression which matches one or more of the  -features of T. It therefore follows that T in raising clauses must carry one or more

-features of T. It therefore follows that T in raising clauses must carry one or more  -features if it is to trigger movement of a nominal carrying

-features if it is to trigger movement of a nominal carrying  -features of its own. Now it clearly cannot be the case that raising to carries both person and number, since if it did we would wrongly predict that raising clauses require a null PRO subject (given that infinitival to assigns null case to its subject by (67) when carrying both person and number). The conclusion we reach, therefore, is that raising to must carry only one

-features of its own. Now it clearly cannot be the case that raising to carries both person and number, since if it did we would wrongly predict that raising clauses require a null PRO subject (given that infinitival to assigns null case to its subject by (67) when carrying both person and number). The conclusion we reach, therefore, is that raising to must carry only one  -feature. But which

-feature. But which  -feature – person or number?

-feature – person or number?

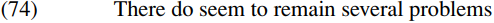

The answer is provided by raising sentences such as the following:

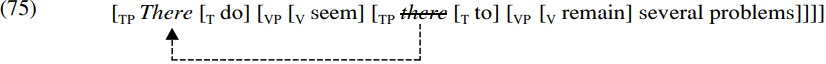

On the assumption that raising to carries an [EPP] feature requiring it to project a subject, it seems reasonable to posit that expletive there will become the specifier of to remain several problems at some stage of derivation, and thereafter be raised up (in the manner shown by the arrow in the skeletal structure in (75) below) to become the specifier of do on the main-clause TP cycle:

This being so, merging there as the specifier of raising to on the subordinate clause TP cycle must satisfy the [EPP] feature of to. It follows that the  -feature carried by to in (75) must match that carried by expletive there. Since we argued that expletive there carries person (but not number), it also follows that to in (75) must carry a person feature. This being so, the [EPP] feature of raising to will require it to project a specifier carrying a person feature, and expletive there clearly satisfies this requirement. (Note that the argument goes through irrespective of whether we follow Chomsky 2001 in positing that there originates as the specifier of to, or Bowers 2002 in assuming that there originates as the specifier of remain and is subsequently raised up to become the specifier of to.)

-feature carried by to in (75) must match that carried by expletive there. Since we argued that expletive there carries person (but not number), it also follows that to in (75) must carry a person feature. This being so, the [EPP] feature of raising to will require it to project a specifier carrying a person feature, and expletive there clearly satisfies this requirement. (Note that the argument goes through irrespective of whether we follow Chomsky 2001 in positing that there originates as the specifier of to, or Bowers 2002 in assuming that there originates as the specifier of remain and is subsequently raised up to become the specifier of to.)

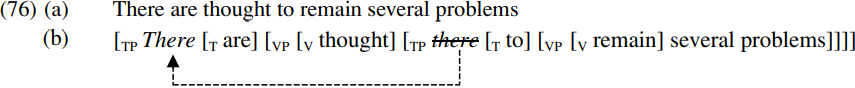

Our conclusion can be generalized from raising sentences like (74/75) to longdistance passives like (76a) below, involving the movement operation arrowed in (76b):

Passive to (i.e. the kind of to found in long-distance passives) cannot carry both person and number features, since otherwise it would wrongly be predicted to require a subject with null case. Since the derivation of (76a) involves a stage at which there is the specifier of to and since there carries person but not number, it seems reasonable to conclude that passive to (like raising to) likewise carries person but not number.

Passive to (i.e. the kind of to found in long-distance passives) cannot carry both person and number features, since otherwise it would wrongly be predicted to require a subject with null case. Since the derivation of (76a) involves a stage at which there is the specifier of to and since there carries person but not number, it seems reasonable to conclude that passive to (like raising to) likewise carries person but not number.

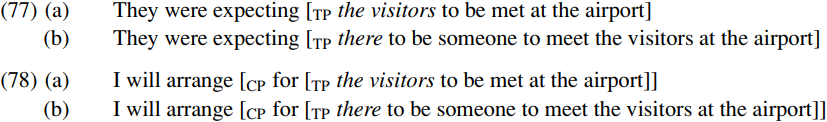

We can generalize our finding still further to infinitival TPs such as those bracketed in (77) and (78) below:

The bracketed TPs in (77) are ECM clauses. Since the visitors originates as the thematic complement of the passive verb met in (77a) but ends up as the subject of [T to], it is clear that the head T of the bracketed complement-clause TP must contain an [EPP] feature and at least one  -feature. Since the infinitive subject can be expletive there in (77b), and since there carries only person, it follows that the head T of an ECM clause must carry a person feature as well as an [EPP] feature. But if we suppose that a non-finite T which carries a full set of person and number features (like the head T of a control clause) assigns null case to its subject, then it is apparent from the fact that the subject of an ECM clause is an overt constituent and hence does not have null case that the head T of an ECM clause must also be defective, and so carry an [EPP] feature and a person feature, but no number feature. Our conclusion can be generalized in a straightforward fashion to for-infinitive structures like those bracketed in (78): if we define ECM structures as structures in which a constituent within TP is assigned case by an external head lying outside the relevant TP, it follows that for-infinitives are also ECM structures.

-feature. Since the infinitive subject can be expletive there in (77b), and since there carries only person, it follows that the head T of an ECM clause must carry a person feature as well as an [EPP] feature. But if we suppose that a non-finite T which carries a full set of person and number features (like the head T of a control clause) assigns null case to its subject, then it is apparent from the fact that the subject of an ECM clause is an overt constituent and hence does not have null case that the head T of an ECM clause must also be defective, and so carry an [EPP] feature and a person feature, but no number feature. Our conclusion can be generalized in a straightforward fashion to for-infinitive structures like those bracketed in (78): if we define ECM structures as structures in which a constituent within TP is assigned case by an external head lying outside the relevant TP, it follows that for-infinitives are also ECM structures.

Our argumentation here leads us to the following more general conclusions:

And these are essentially the assumptions made in Chomsky (2001).

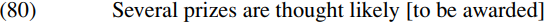

In the light of the assumptions in (79), consider the derivation of the following sentence:

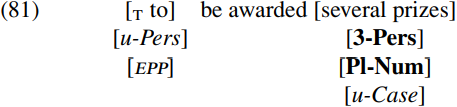

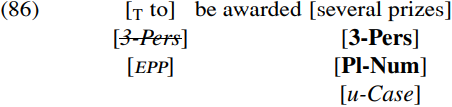

Since the bracketed infinitive complement in (80) is a defective clause, [T to] will carry uninterpretable [EPP] and person features (but no number feature) in accordance with (79i,iii). This means that at the point where to is merged with its complement we have the structure shown in skeletal form below:

Since [T to] is the highest head in the structure at this point and is active by virtue of its uninterpretable person feature, [T to] serves as a probe which searches for an active goal and locates several prizes, which is active by virtue of its unvalued case feature. The goal several prizes values the unvalued person feature of to as third person and (by virtue of being  -complete) deletes it. The unvalued case feature of several prizes cannot be valued or deleted by to, since to is

-complete) deletes it. The unvalued case feature of several prizes cannot be valued or deleted by to, since to is  -incomplete (by virtue of having no number feature), and only a finite/non-finite

-incomplete (by virtue of having no number feature), and only a finite/non-finite  -complete T can assign nominative/null case to a goal, and only a

-complete T can assign nominative/null case to a goal, and only a  - complete

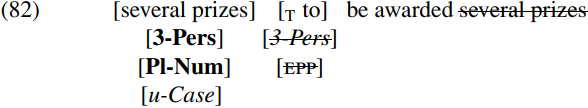

- complete  can delete a matching feature of ß. The [EPP] feature of to is deleted by movement of several prizes to spec-TP in accordance with the EPP Generalization (45iii), thereby deriving the structure (82) below (simplified in various ways, including by showing the deleted trace of several prizes without its features):

can delete a matching feature of ß. The [EPP] feature of to is deleted by movement of several prizes to spec-TP in accordance with the EPP Generalization (45iii), thereby deriving the structure (82) below (simplified in various ways, including by showing the deleted trace of several prizes without its features):

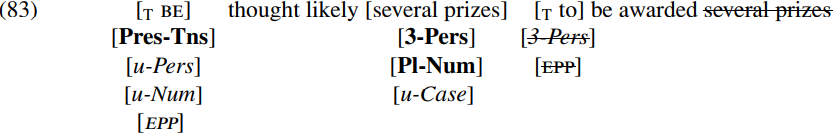

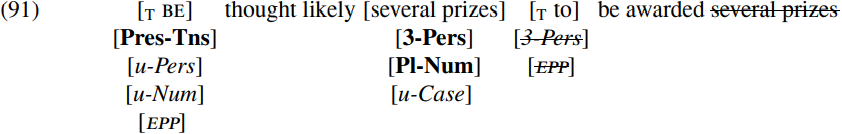

Merging the structure (82) with the raising adjective likely, merging the resulting AP with the passive verb thought and then merging the resulting VP with a finite present-tense T constituent containing BE will derive:

Because it is the highest head in the structure and is active by virtue of its uninterpretable  -features, BE serves as a probe which searches for an active goal and locates several prizes. By virtue of being

-features, BE serves as a probe which searches for an active goal and locates several prizes. By virtue of being  -complete, the goal several prizes values and deletes the uninterpretable person/number features of the probe BE. By virtue of being finite and

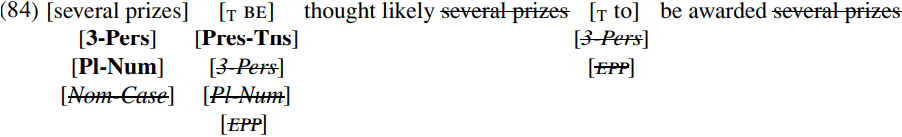

-complete, the goal several prizes values and deletes the uninterpretable person/number features of the probe BE. By virtue of being finite and  -complete, BE values the unvalued case feature of several prizes as nominative, and deletes it. The [EPP] feature of be is deleted by moving several prizes to spec-TP in accordance with (45iii), so deriving:

-complete, BE values the unvalued case feature of several prizes as nominative, and deletes it. The [EPP] feature of be is deleted by moving several prizes to spec-TP in accordance with (45iii), so deriving:

The resulting TP is subsequently merged with a null declarative complementizer, and BE is ultimately spelled out as are. Since all unvalued features have been valued and all uninterpretable features have been deleted, the derivation converges (i.e. results in a well-formed structure which can be assigned an appropriate phonetic representation and an appropriate semantic representation)

The resulting TP is subsequently merged with a null declarative complementizer, and BE is ultimately spelled out as are. Since all unvalued features have been valued and all uninterpretable features have been deleted, the derivation converges (i.e. results in a well-formed structure which can be assigned an appropriate phonetic representation and an appropriate semantic representation)

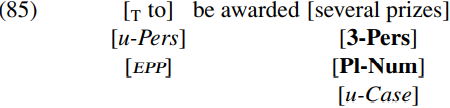

Now let’s return to take another look at the derivation of our earlier sentence (1) There are thought likely to be awarded several prizes. Let’s adopt Chomsky’s TP analysis of expletives and suppose that we have reached the stage of derivation in (81) above, repeated as (85) below:

As before, to serves as a probe and identifies several prizes as an active goal. Since several prizes is  -complete, it can not only value the unvalued person feature of to but also delete it, yielding:

-complete, it can not only value the unvalued person feature of to but also delete it, yielding:

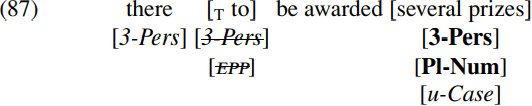

Since the goal several prizes is an indefinite expression, the [EPP] feature of to can be deleted by merging expletive there in spec-TP in accordance with the EPP Generalization (45i), deriving:

Since there is the highest head in the structure and is active by virtue of its uninterpretable person feature, it serves as a probe, and picks out to as a matching goal containing a person feature. However, since to is defective (in that it has no number feature), it cannot delete the uninterpretable person feature on there. (We assume here that several prizes cannot serve as a possible goal for there, because agreement is a relation between a noun/pronoun expression like there and a T constituent like to, not a relation between two noun/pronoun expressions like there and several prizes.)

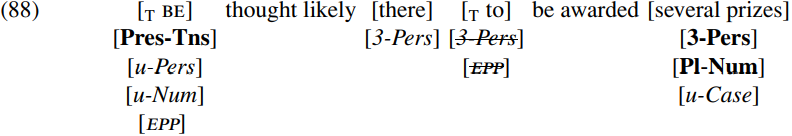

Merging the TP in (87) with the raising adjective likely, merging the resulting AP with the passive verb thought and merging the resulting VP with a present tense T containing BE will derive:

At this point, [T BE] is the highest head in the structure and so serves as a probe. Its uninterpretable person and number features make it active, and mean that [T BE] looks for active nominal goals which have person and/or number features.

However, there are two such active nominal goals which are accessible to the probe [T BE] in (88) – namely the expletive pronoun there (active by virtue of its uninterpretable third-person feature) and the quantifier phrase several prizes (active by virtue of its uninterpretable case feature, and carrying both person and number features). Both are accessible to [T BE] in terms of the Phase Impenetrability Condition (55) since neither is c-commanded by a phase head (i.e. by a complementizer or by a transitive verb). Let’s suppose (consistent with Chomsky 2001 and with our earlier discussion of (50) above) that when a probe locates more than one active goal, it undergoes simultaneous multiple agreement with all active goals accessible to it – in other words, the probe BE simultaneously agrees with both there and several prizes. The unvalued person feature of BE will be valued as third person via Feature Matching with the third-person goals there and several prizes; the unvalued number feature of BE will be valued as plural via agreement with the plural goal several prizes. The unvalued case feature on the goal several prizes will be valued as nominative (and deleted) by the  -complete probe BE because the two match in person and number and BE carries finite tense. The uninterpretable person/number features of the probe BE can in turn be deleted by the

-complete probe BE because the two match in person and number and BE carries finite tense. The uninterpretable person/number features of the probe BE can in turn be deleted by the  -complete goal several prizes. In accordance with (45iii) and the Attract Closest Principle, the [EPP] feature of BE attracts the closest active goal (namely there) to move to become the specifier of BE (movement resulting in deletion of the [EPP] feature on BE), deriving:

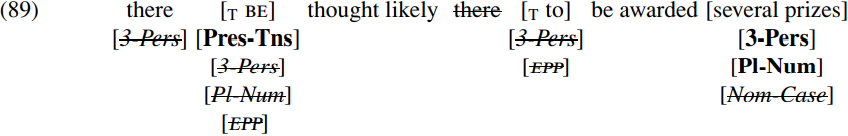

-complete goal several prizes. In accordance with (45iii) and the Attract Closest Principle, the [EPP] feature of BE attracts the closest active goal (namely there) to move to become the specifier of BE (movement resulting in deletion of the [EPP] feature on BE), deriving:

The resulting structure will then be merged with a null declarative complementizer, and BE will ultimately be spelled out as the third-person-plural present-tense form are. As required, all uninterpretable features have been deleted from (89), so only the bold interpretable features are seen by the semantic component.

The resulting structure will then be merged with a null declarative complementizer, and BE will ultimately be spelled out as the third-person-plural present-tense form are. As required, all uninterpretable features have been deleted from (89), so only the bold interpretable features are seen by the semantic component.

Note that an important assumption which is incorporated into the analysis presented here is that the  -features of T agree with every goal which is accessible to them (giving rise to multiple agreement), but that (in consequence of the Attract Closest Principle) the [EPP] feature of T only triggers movement of the closest goal to spec-TP.

-features of T agree with every goal which is accessible to them (giving rise to multiple agreement), but that (in consequence of the Attract Closest Principle) the [EPP] feature of T only triggers movement of the closest goal to spec-TP.

Under the analysis presented here (in which all instances of infinitival to carry an [EPP] feature), an important question which arises is how we account for the ungrammaticality of sentences like:

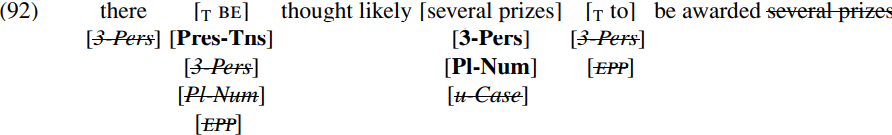

Consider first how (90) might be derived, before considering why it is ill-formed. The derivation proceeds along familiar lines until we reach the stage of derivation in (83) above, repeated as (91) below:

As before, the case feature of several prizes is valued as nominative and deleted by [T BE], and conversely the person/number features of BE are valued and deleted by several prizes. Let’s suppose that the lexical array contains expletive there and that the [EPP] feature of BE is deleted by merging there in spec-TP, and that the uninterpretable third-person feature of there is deleted by the  -complete [T BE], so deriving:

-complete [T BE], so deriving:

(92) is then merged with a null declarative complementizer, and BE is ultimately spelled out as are. Since the resulting structure contains no unvalued or uninterpretable features, we expect the corresponding sentence (90) to be well-formed. But it is ungrammatical. Why should this be?

(92) is then merged with a null declarative complementizer, and BE is ultimately spelled out as are. Since the resulting structure contains no unvalued or uninterpretable features, we expect the corresponding sentence (90) to be well-formed. But it is ungrammatical. Why should this be?

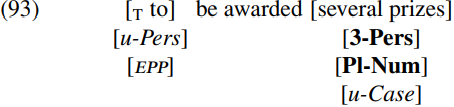

Chomsky’s answer is that Merge is a more primitive and less complex operation than Move and that ‘Simple operations preempt more complex ones’ (Chomsky 1998, p. 18). Merge is a more primitive relation than Move in that other combinatorial systems (like the artificial languages used in mathematics, logic or computer science) employ Merge but not Move. Move is more complex than Merge because it is a composite agree+ copy+ merge+ pied- pipe operation. It therefore follows from ‘complexity considerations’ (Chomsky 1998, p. 18) that spec-TP must be filled by merger if the lexical array (i.e. the set of items taken out of the lexicon to build the relevant sentence structure) contains an expletive, with movement to spec-TP being used only as a last resort (i.e. where the lexical array contains no expletive). As Chomsky (1998, p. 17) puts it, ‘Merge preempts the more complex operation Move’ (though see Shima 2000 for a dissenting view). Since the sentence in (90) contains expletive there, it is clear that the lexical array for (90) includes an expletive. In the light of this observation, let’s return to the earlier stage of derivation represented in (81) above, repeated as (93) below:

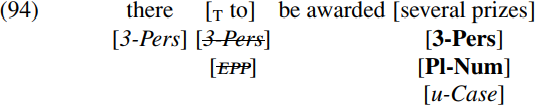

Complexity considerations – more explicitly what Chomsky (1999, p. 5) refers to as ‘preference of Merge over (more complex) Move’ – will require the [EPP] feature of [T to] be satisfied by merging expletive there in spec-TP, so resulting in (87) above, repeated as (94) below:

Subsequently, the derivation will proceed through the steps discussed in (88) and (89) above, ultimately deriving the CP structure associated with There are thought likely to be awarded several prizes.

To revert to terminology, if T in English always has an [EPP] feature, A-movement will always be a local operation which (in complex structures where an argument moves out of one or more lower TP constituents to become the subject of a higher TP) applies in a successive-cyclic fashion, with the relevant argument moving to become the subject of a lower TP before going on to become the subject of a higher TP. Since we saw that head movement is also successive-cyclic (in that a moved head moves into the next highest head position within the structure immediately containing it), the greater generalization would appear to be that all movement is local (and hence successive-cyclic in complex structures), so that any moved constituent moves into the closest appropriate landing site above it (as argued in Rizzi 2001a). If so, we would expect to find that wh-movement is also a local (hence successive-cyclic) operation. And indeed, theoretical considerations suggest that it must be.

We have seen that CPs and transitive VPs are phases, and that the Phase Impenetrability Condition/PIC (55) prevents a constituent which is c-commanded by a complementizer or a transitive verb from being attracted by an external head which c-commands the CP/VP containing the relevant complementizer/transitive verb. PIC turns out to have important consequences for how wh-movement operates in complex sentences such as:

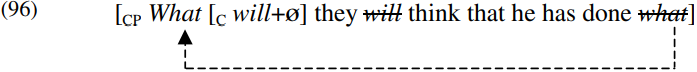

The wh-pronoun what originates as the thematic complement of the transitive verb done, and it might at first sight seem as if it moves from being the complement of the transitive verb done to becoming the specifier of the C constituent containing the inverted auxiliary will in a single step like that shown in highly simplified form in (96) below:

And indeed, this is precisely what we tacitly assumed. However, a single-step movement operation like that shown in (96) will involve three violations of the Phase Impenetrability Condition, since it involves the bracketed C constituent serving as a probe which attracts the wh-pronoun what to move out of a transitive VP headed by done, out of a CP headed by that, and out of a further transitive VP headed by think. The only way of avoiding violation of PIC is for wh-movement to apply in a successive-cyclic fashion, moving what first to the front of the transitive VP headed by do, then to the front of the complement clause CP headed by that, then to the front of the transitive VP headed by think, and finally to the front of the main-clause CP headed by the null complementizer to which the inverted auxiliary will adjoins. It would not be appropriate for us to look in more detail at the successive-cyclic nature of wh-movement at this point, until we have taken a closer look at the internal structure of verb phrases in and at the nature of phases: hence we postpone discussion of this until.