تاريخ الفيزياء

علماء الفيزياء

الفيزياء الكلاسيكية

الميكانيك

الديناميكا الحرارية

الكهربائية والمغناطيسية

الكهربائية

المغناطيسية

الكهرومغناطيسية

علم البصريات

تاريخ علم البصريات

الضوء

مواضيع عامة في علم البصريات

الصوت

الفيزياء الحديثة

النظرية النسبية

النظرية النسبية الخاصة

النظرية النسبية العامة

مواضيع عامة في النظرية النسبية

ميكانيكا الكم

الفيزياء الذرية

الفيزياء الجزيئية

الفيزياء النووية

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء النووية

النشاط الاشعاعي

فيزياء الحالة الصلبة

الموصلات

أشباه الموصلات

العوازل

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء الصلبة

فيزياء الجوامد

الليزر

أنواع الليزر

بعض تطبيقات الليزر

مواضيع عامة في الليزر

علم الفلك

تاريخ وعلماء علم الفلك

الثقوب السوداء

المجموعة الشمسية

الشمس

كوكب عطارد

كوكب الزهرة

كوكب الأرض

كوكب المريخ

كوكب المشتري

كوكب زحل

كوكب أورانوس

كوكب نبتون

كوكب بلوتو

القمر

كواكب ومواضيع اخرى

مواضيع عامة في علم الفلك

النجوم

البلازما

الألكترونيات

خواص المادة

الطاقة البديلة

الطاقة الشمسية

مواضيع عامة في الطاقة البديلة

المد والجزر

فيزياء الجسيمات

الفيزياء والعلوم الأخرى

الفيزياء الكيميائية

الفيزياء الرياضية

الفيزياء الحيوية

الفيزياء العامة

مواضيع عامة في الفيزياء

تجارب فيزيائية

مصطلحات وتعاريف فيزيائية

وحدات القياس الفيزيائية

طرائف الفيزياء

مواضيع اخرى

Cellular biology

المؤلف:

J. M. D. COEY

المصدر:

Magnetism and Magnetic Materials

الجزء والصفحة:

557

8-3-2021

3220

Cellular biology

Many reports can be found in the literature on effects of static or low-frequency magnetic fields on cellular processes, but very few have been reproducibly established.

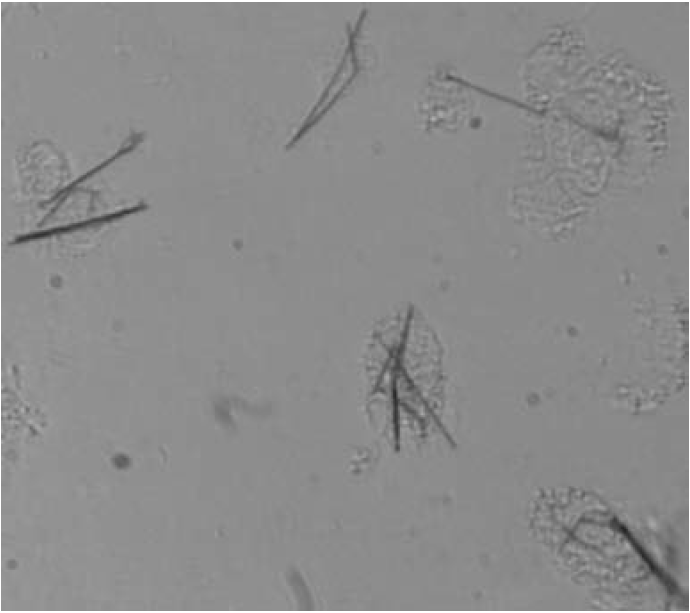

Figure 1: Differentiated THP1 macrophages, which have internalized nickel wires 20 μm long and 200 nm in diameter (Courtesy of A. Prina-Mellor).

However, magnetic methods are beginning to make a contribution to the study of cells, and subcellular structures such as proteins and biomolecules. Generally, these studies make use of magnetic micro- or nanoparticles whose sizes are compatible with the sizes of the biological structures they are used to manipulate (10–100 μm for cells, 10–100 nm for proteins). The microparticles normally incorporate many superparamagnetic nanoparticles in a biocompatible polymer microbead, with a fill fraction 0.1 < f < 0.8. The surface of the bead can be functionalized for a specific biochemical reaction, with an antibody for example. A single coated magnetic nanoparticle may be used to manipulate protein or similar structures. The response of the magnetic label is usually linear in the gradient of applied fields, which are of order 10–100 kAm−1 for miniature electromagnets, and may be larger if permanent magnets are used. Magnetic nanowires, Fig. 1, have the advantage that information can be recorded along the length of the label if it is segmented and the segments are permanently magnetized in opposite directions. Such magnetic barcodes can be used to label cells or proteins, and they can be detected via the characteristic patterns of stray field they produce, by using magnetoresistive sensors in a microfluidic channel, for example. When a magnetic microbead or nanowire is attached to a cell or biomolecule, the object can be manipulated by field gradient force

f ≈ ∇(m· B), (1)

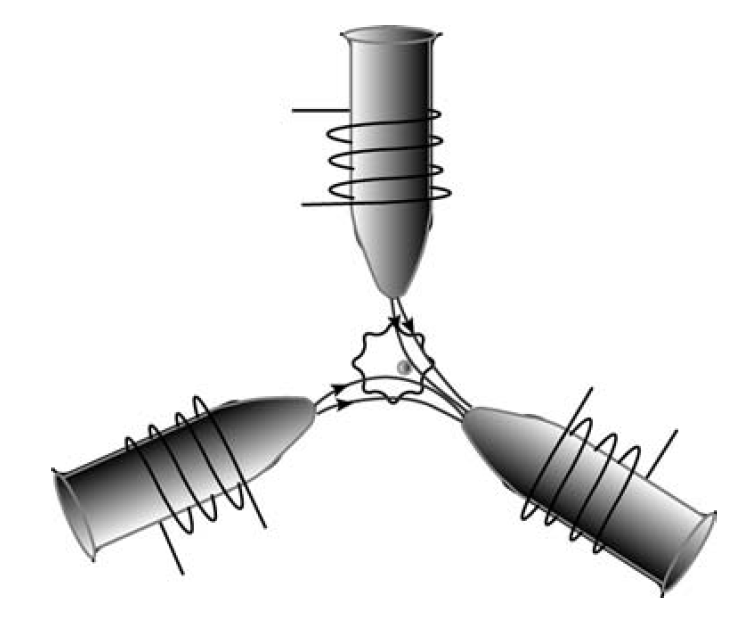

where m is the induced moment of the bead. The studies are interesting because mechanical stress and morphology can regulate cellular functions, and it is important to be able to measure mechanical properties on the appropriate scale. Controlled stresses and forces can be applied via the magnetic labels in biological micromanipulators known as magnetic tweezers. One arrangement has three or four miniature electromagnets arranged in a circle, and the field is varied by the electric currents in microcoils, Fig. 2. The force needed to manoeuvre a bead through the cytoplasm of a living cell is of

Figure 2: Magnetic tweezers. The currents in the coils are used to create a magnetic field that exerts force on a microbead in the cell.

order 1–10 piconewtons. For a particle of diameter 200 nm and magnetization 100 kA m−1, a field gradient of order 104 T m−1 is needed to deliver the required force. Using lithographically patterned Co–Fe poles, these field gradients can be achieved over dimensions of order 10 μm.

Larger field gradients are available with small permanent magnets. The mechanical properties of individual biomolecules such as coiled DNA can be determined by attaching a magnetic bead to one end, and applying force with permanent magnet tweezers.

الاكثر قراءة في المغناطيسية

الاكثر قراءة في المغناطيسية

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)