علم الكيمياء

تاريخ الكيمياء والعلماء المشاهير

التحاضير والتجارب الكيميائية

المخاطر والوقاية في الكيمياء

اخرى

مقالات متنوعة في علم الكيمياء

كيمياء عامة

الكيمياء التحليلية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء التحليلية

التحليل النوعي والكمي

التحليل الآلي (الطيفي)

طرق الفصل والتنقية

الكيمياء الحياتية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الحياتية

الكاربوهيدرات

الاحماض الامينية والبروتينات

الانزيمات

الدهون

الاحماض النووية

الفيتامينات والمرافقات الانزيمية

الهرمونات

الكيمياء العضوية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء العضوية

الهايدروكاربونات

المركبات الوسطية وميكانيكيات التفاعلات العضوية

التشخيص العضوي

تجارب وتفاعلات في الكيمياء العضوية

الكيمياء الفيزيائية

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الفيزيائية

الكيمياء الحرارية

حركية التفاعلات الكيميائية

الكيمياء الكهربائية

الكيمياء اللاعضوية

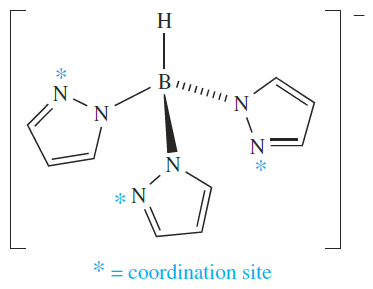

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء اللاعضوية

الجدول الدوري وخواص العناصر

نظريات التآصر الكيميائي

كيمياء العناصر الانتقالية ومركباتها المعقدة

مواضيع اخرى في الكيمياء

كيمياء النانو

الكيمياء السريرية

الكيمياء الطبية والدوائية

كيمياء الاغذية والنواتج الطبيعية

الكيمياء الجنائية

الكيمياء الصناعية

البترو كيمياويات

الكيمياء الخضراء

كيمياء البيئة

كيمياء البوليمرات

مواضيع عامة في الكيمياء الصناعية

الكيمياء الاشعاعية والنووية

Ferromagnetism, antiferromagnetism and ferrimagnetism

المؤلف:

CATHERINE E. HOUSECROFT AND ALAN G. SHARPE

المصدر:

INORGANIC CHEMISTRY

الجزء والصفحة:

2th ed p 583

22-2-2017

1539

Ferromagnetism, antiferromagnetism and ferrimagnetism

Whenever we have mentioned magnetic properties so far, we have assumed that metal centres have no interaction with each other (Figure 1.1a). This is true for substances where the paramagnetic centres are well separated from each other by diamagnetic species; such systems are said to be magnetically dilute. When the paramagnetic species are very close together (as in the bulk metal) or are separated by a species that can transmit magnetic interactions (as in many d-block metal oxides, fluorides and chlorides), the metal centres may interact (couple) with one another. The interaction may give rise to ferromagnetism or antiferromagnetism (Figures 1.1b and 1.1c).

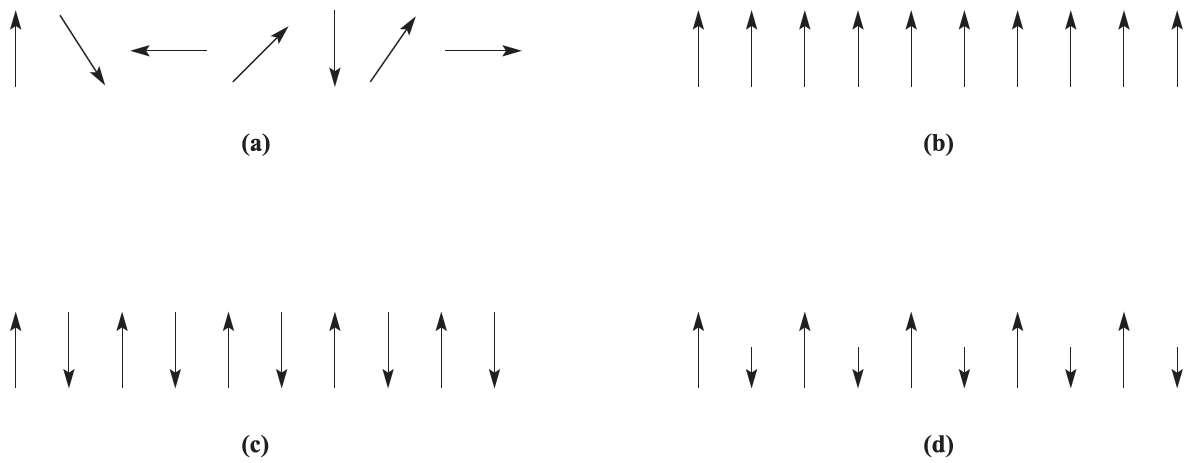

Fig. 1.1 Representations of (a) paramagnetism, (b) ferromagnetism, (c) antiferromagnetism and (d) ferrimagnetism.

In a ferromagnetic material, large domains of magnetic dipoles are aligned in the same direction; in an antiferromagnetic material, neighbouring magnetic dipoles are aligned in opposite directions. Ferromagnetism leads to greatly enhanced paramagnetism as in iron metal at temperatures of up to 1041K (the Curie temperature, TC), above which thermal energy is sufficient to overcome the alignment and normal paramagnetic behavior prevails. Antiferromagnetism occurs below the Neel temperature, TN; as the temperature decreases, less thermal energy is available and the paramagnetic susceptibility falls rapidly. The classic example of antiferromagnetism is MnO which has a NaCl-type lattice and a Neel temperature of 118 K. Neutron diffraction is capable of distinguishing between sets of atoms having opposed magnetic moments and reveals that the unit cell of MnO at 80K is double the one at 293 K; this indicates that in the conventional unit cell metal atoms at adjacent corners have opposed moments at 80K and that the cells must be stacked to produce the ‘true’ unit cell. More complex behavior may occur if some moments are systematically aligned so as to oppose others, but relative numbers or relative values of the moments are such as to lead to a finite resultant magnetic moment: this is ferrimagnetism and is represented schematically in Figure 1.1d.

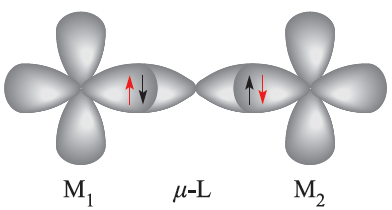

When a bridging ligand facilitates the coupling of electron spins on adjacentmetal centres, the mechanismis one of superexchange. This is shown schematically in diagram 1.1, in which the unpaired metal electrons are represented in red.

(1.1)

In a superexchange pathway, the unpaired electron on the first metal centre, M1, interacts with a spin-paired pair of electrons on the bridging ligand with the result that the unpaired electron on M2 is aligned in an antiparallel manner with respect to that on M1. 1.2 Thermodynamic aspects: ligand field stabilization energies (LFSE) Trends in LFSE So far, we have considered Δoct (or Δtet) only as a quantity derived from electronic spectroscopy and representing the energy required to transfer an electron from a t2g to an eg level (or from an e to t2 level). However, chemical significance can be attached to these values.

(1.2 )

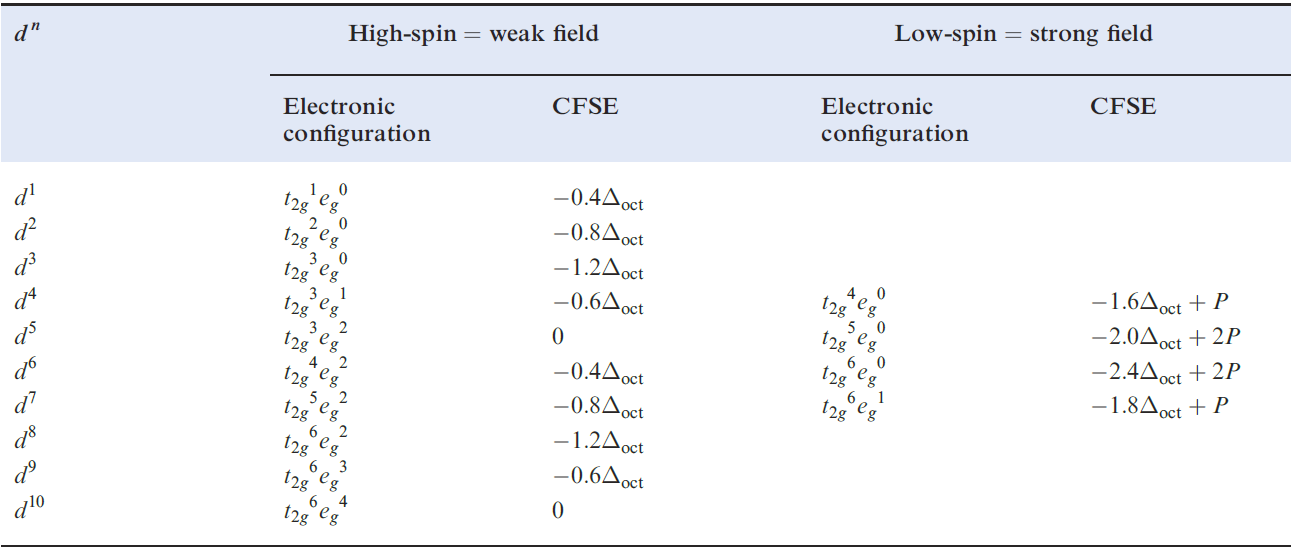

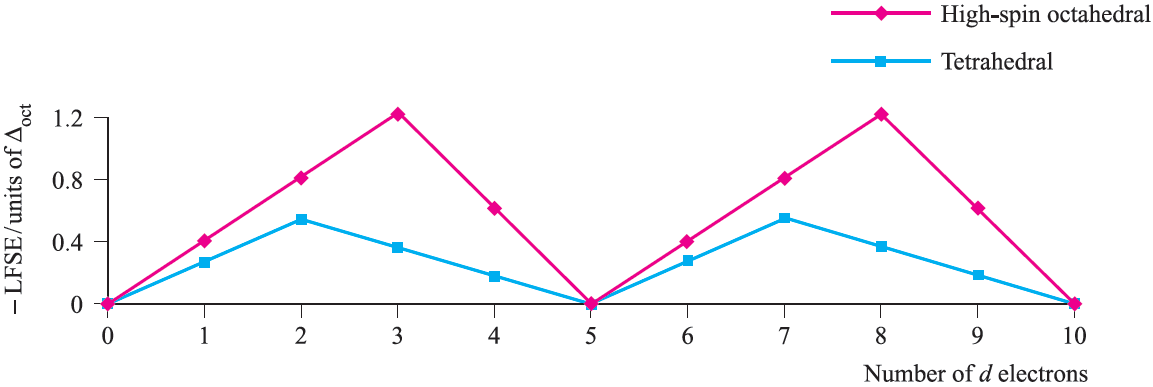

Table 1.1 showed the variation in crystal field stabilization energies (CFSE) for high- and low-spin octahedral systems; the trend for high-spin systems is restated in Figure 1.2, where it is compared with that for a tetrahedral field, Δtet being expressed as a fraction of Δoct .

Table 1.1 Octahedral crystal field stabilization energies (CFSE) for dn configurations; pairing energy, P, terms are included where appropriate . High- and low-spin octahedral complexes are shown only where the distinction is appropriate.

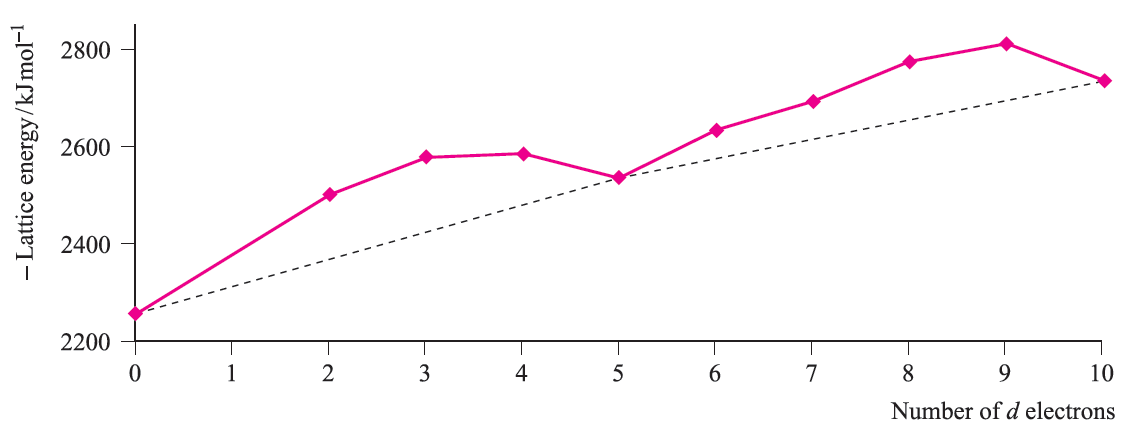

Note the change from CFSE to LFSE in moving from Table 1.1 to Figure 1.2; this reflects the fact that we are now dealing with ligand field theory and ligand field stabilization energies. In the discussion that follows, we consider relationships between observed trends in LFSE values and selected thermodynamic properties of high-spin compounds of the d-block metals. Lattice energies and hydration energies of Mn+ ions Figure 1.3 shows a plot of experimental lattice energy data for metal(II) chlorides of first row d-block elements. In each salt, the metal ion is high-spin and lies in an octahedral environment in the solid state. The ‘double hump’ in Figure 1.3 is reminiscent of that in Figure 1.2, albeit with respect to a reference line which shows a general increase in lattice energy as the period is crossed. Similar plots can be obtained for species such as MF2, MF3 and [MF6]3-, but for each series, only limited data are available and complete trends cannot be studied.

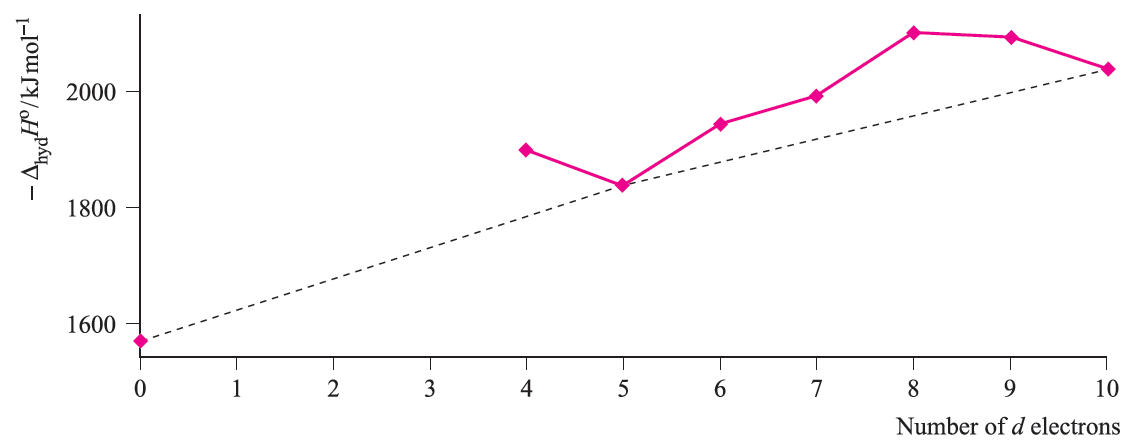

Water is a weak-field ligand and [M(H2O(6]2+ ions of the first row metals are high-spin. The relationship between absolute enthalpies of hydration of M2+ ions and d n configuration is shown in Figure 1.4, and again we see the ‘double-humped’ appearance of Figures 1.2 and 1.3.

Fig. 1.2 Ligand field stabilization energies as a function of Δoct for high-spin octahedral systems and for tetrahedral systems; Jahn–Teller effects for d4 and d9 configurations have been ignored.

Fig. 1.3 Lattice energies (derived from Born–Haber cycle data) for MCl2 where M is a first row d-block metal; the point for d0 corresponds to CaCl2. Data are not available for scandium where the stable oxidation state is 3.

For each plot in Figures 1.3 and 1.4, deviations from the reference line joining the d0, d5 and d10 points may be taken as measures of ‘thermochemical LFSE’ values. In general, the agreement between these values and those calculated from the values of Δoct derived from electronic spectroscopic data are fairly close. For example, for [Ni)H2O(6]2+, the values of LFSE(thermochemical) and LFSE(spectroscopic) are 120 and 126 kJ mol-1 respectively; the latter comes from an evaluation of 1:2 Δoct where Δoct is determined from the electronic spectrum of [Ni(H2O)6]2+ to be 8500 cm-1.

Fig. 1.4 Absolute enthalpies of hydration of the M2+ ions of the first row metals; the point for d0 corresponds to Ca2+. Data are not available for Sc2+, Ti2+ and V2+.

We have to emphasize that this level of agreement is fortuitous; if we look more closely at the problem, we note that only part of the measured hydration enthalpy can be attributed to the first coordination sphere of six H2O molecules, and, moreover, the definitions of LFSE(thermochemical) and LFSE(spectroscopic) are not strictly equivalent. In conclusion, we must make the very important point that, interesting and useful though discussions of ‘double-humped’ graphs are in dealing with trends in the thermodynamics of high-spin complexes, they are never more than approximations. It is crucial to remember that LFSE terms are only small parts of the total interaction energies (generally <10%).

الاكثر قراءة في كيمياء العناصر الانتقالية ومركباتها المعقدة

الاكثر قراءة في كيمياء العناصر الانتقالية ومركباتها المعقدة

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)