تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

Functions-Basic Definitions

المؤلف:

Ivo Düntsch and Günther Gediga

المصدر:

Sets, Relations, Functions

الجزء والصفحة:

35-38

14-2-2017

2230

Definition 1.1. A function is an ordered triple 〈f,A, B〉 such that

1. A and B are sets, and f ⊆ A × B,

2. For every x ∈ A there is some y ∈ B such that 〈x ,y〉 ∈ f

3. If 〈x ,y〉 ∈ f and 〈x ,z〉 ∈ f, then y = z; in other words, the assignment is unique in the sense that an x ∈ A is assigned at most one element of B.

A is called the domain of f, and B its codomain.

It is customary to write the function 〈f,A, B〉 as f : A → B. Also, if 〈x ,y〉 ∈ f, then we will usually write y = f(x), and call y the image of x under f.

The set {y ∈ B : There is an x ∈ A such that y = f(x)} is called the range of f.

Observe that the range of f is always a subset of the codomain. Observe carefully the distinction between f(x) and f: Whereas f(x) is an element of the codomain, f is the rule of assignment, conveniently expressed as a subset of A × B.

Suppose that f : A → B and g : C → D are functions. It follows from the definition of a function that they are equal if and only if

1. A = C,

2. B = D,

3. f = g.

If for a function f : A → B it is clear what A and B are, we sometimes call the function simply f, but we must keep in mind that a function is only properly defined if we also give a domain and a codomain!

Usually, after having agreed on a domain and a codomain, f is given by a rule,

e.g. f(x) = x2 , f(t) = sin t,f(n) = n + 1. As in the previous section

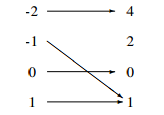

with relations, we sometimes use a diagram to describe a function; for example, the diagram of Figure 1.1 describes the function f : A → B, where A = {1, −1, 0, −2} is the domain of f,B = {1, 0, 2, 4, } is its codomain, and f = {〈1, 1〉,〈−1, 1〉,〈0, 0〉,〈−2, 4〉}.

Figure 1.1: Function arrow diagram

Observe that for all x ∈ A, f(x) = x2 . This can also be indicated by writing x → x2 .

The definition of a function implies that each element of A is the origin of exactly one arrow; it does not imply that at each element of B is the target of an arrow, or that only one arrow from A points to a single element of B. Functions with these properties have special names, and we shall look at them in a later section.

Definition 1.2. Let f : A → B be a function.

1. If A = B and f(x) = x for all x ∈ A, the f is called the identity function on A, and it is denoted by idA.

2. If A ⊆ B and f(x) = x for all x ∈ A, then f is called the inclusion function from A to B, or, if no confusion can arise, simply the inclusion. Observe that, if A = B and f is the inclusion, then f is in fact the identity on A.

3. If f(x) = x for some x ∈ A, then x is called a fixed point of f.

4. If f(x) = b for all x ∈ A, then f is called a constant function.

5. If g : C → D is a function such that A ⊆ C, B ⊆ D, and f ⊆ g, then g is

called an extension of f over C, and f is called the restriction of g to A.

While a function may have many different extension, it can only have one restriction to a subset of its domain. The following diagrams shall illustrate these situations:

Consider the assignment h(x) = (sin x)2 , and suppose that dom h = codom h = R. To find h(x) for a given x, we do two things:

1. First find sin x and set y = sin x;

2. Then find y2.

If we look close enough, we find that we have actually used two functions to find h(x):

1. f : R → R, f(x) = sin x,

2. g : R → R, g(y) = y2,

This shows that h(x) = g(f(x)): We have first applied f to x, found that f(x) is an element of dom g, and then applied g to f(x). This brings us to

Definition 1.3. Let f : A → B and g : C → D be functions such that ran f ⊆ dom g. Then the function g ◦ f : A → C defined by (g ◦ f)(x) = g(f(x)) is called the (functional) composition of f and g.

the reason for using a different interpretation of composition for functions is historical, and we shall not go into details.

Lemma 1.1. If f and g are functions such that ran f ⊆ dom g, then dom(g ◦ f) = dom f, and codom(g ◦ f) = codom g.

Proof. This follows immediately from the definition of composite functions.

One the most useful properties of functional composition is the following:

Lemma .1.2. Let f : A → B, g : B → C, h : C → D be functions. Then, h ◦ (g ◦ f) = (h ◦ g) ◦ f, i.e. the composition of functions is associative.

Proof. Let p = h ◦ (g ◦ f), and q = (h ◦ g) ◦ f; to show that two functions are equal we use the remarks following to find their domains and co-domains.

Looking first at p, we see that p is the composite of the functions g ◦ f and h, so, we will have to look at g ◦ f first. Now, dom(g ◦ f) = dom f = A by Lemma

1.1, thus, dom p = dom h ◦ (g ◦ f) = A. Next,

codom p = codom h ◦ (g ◦ f) = codom h = D, also by Lemma 1.1.

Looking at q, we see by a similar reasoning that dom q = A and that codom q = codom(h ◦ g). Since codom(h ◦ g) = codom h, we have codom h = D; thus, we find that dom p = dom q, and codom p = codom q.

All that is left to show is that p = q, i.e. that p(x) = q(x) for all x ∈ A. Let x ∈ A;

then,

p(x) = (h ◦ (g ◦ f))(x)

= h((g ◦ f)(x))

= h(g(f(x)))

= (h ◦ g)(f(x))

= ((h ◦ g) ◦ f)(x)

= q(x).

Thus, (p,A, D) = (q, A, D)

الاكثر قراءة في نظرية المجموعات

الاكثر قراءة في نظرية المجموعات

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)