تاريخ الرياضيات

الاعداد و نظريتها

تاريخ التحليل

تار يخ الجبر

الهندسة و التبلوجي

الرياضيات في الحضارات المختلفة

العربية

اليونانية

البابلية

الصينية

المايا

المصرية

الهندية

الرياضيات المتقطعة

المنطق

اسس الرياضيات

فلسفة الرياضيات

مواضيع عامة في المنطق

الجبر

الجبر الخطي

الجبر المجرد

الجبر البولياني

مواضيع عامة في الجبر

الضبابية

نظرية المجموعات

نظرية الزمر

نظرية الحلقات والحقول

نظرية الاعداد

نظرية الفئات

حساب المتجهات

المتتاليات-المتسلسلات

المصفوفات و نظريتها

المثلثات

الهندسة

الهندسة المستوية

الهندسة غير المستوية

مواضيع عامة في الهندسة

التفاضل و التكامل

المعادلات التفاضلية و التكاملية

معادلات تفاضلية

معادلات تكاملية

مواضيع عامة في المعادلات

التحليل

التحليل العددي

التحليل العقدي

التحليل الدالي

مواضيع عامة في التحليل

التحليل الحقيقي

التبلوجيا

نظرية الالعاب

الاحتمالات و الاحصاء

نظرية التحكم

بحوث العمليات

نظرية الكم

الشفرات

الرياضيات التطبيقية

نظريات ومبرهنات

علماء الرياضيات

500AD

500-1499

1000to1499

1500to1599

1600to1649

1650to1699

1700to1749

1750to1779

1780to1799

1800to1819

1820to1829

1830to1839

1840to1849

1850to1859

1860to1864

1865to1869

1870to1874

1875to1879

1880to1884

1885to1889

1890to1894

1895to1899

1900to1904

1905to1909

1910to1914

1915to1919

1920to1924

1925to1929

1930to1939

1940to the present

علماء الرياضيات

الرياضيات في العلوم الاخرى

بحوث و اطاريح جامعية

هل تعلم

طرائق التدريس

الرياضيات العامة

نظرية البيان

Sets-Set Operations

المؤلف:

Ivo Düntsch and Günther Gediga

المصدر:

Sets, Relations, Functions

الجزء والصفحة:

14-17

14-2-2017

2064

In this section we shall encounter several ways of obtaining sets from previously given ones.

Definition 1. 1. Let A and B be given sets; then

1. The intersection A ∩ B of A and B is defined by

A ∩ B = {x : x ∈ A and x ∈ B}

If A ∩ B = ∅, then A and B are called disjoint.

2. The union A ∪ B of A and B is defined by

A ∪ B = {x : x ∈ A or x ∈ B}.

3. The set difference A B of A and B is the set

A B = {x : x ∈ A and x ∉ B}.

A B is also called the relative complement of B with respect to A.

If U is a given universal set, then U A is just called the complement of A, written as −A.

Observe that A ∩ B is the set of those objects which are simultaneously in both A and B, while A ∪ B is the set of those objects which are in A or in B or in both of them; observe carefully that we do not interpret “or” as exclusive; in our terminology, “or” always means “one, or the other, or both”.

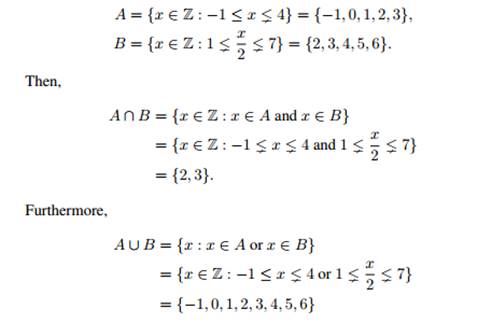

Example 1. 1. Let

2. Let g1 and g2 be two non–parallel lines in the plane. Then, their intersection g1 ∩ g2 is just the point where the two lines meet. Their union g1 ∪ g2 is the set of all points which are on g1 or on g2 (or on both lines).

3. Let R be the set of all station wagons in Iceland at a given time, and let S be the set of all white cars in Iceland. Then S ∩ T is the set of all white station wagons in Iceland, and S ∪ T is the set of all those cars in Iceland which are a station wagon or which are white or both.

4. Let U = N, and A = {x ∈ N : x is prime}. Then −A is the set of all those natural numbers which are less than 2 or have at least three divisors.

5. Let U = N, and A be the set of all even natural numbers. Then −A is the set of all odd natural numbers.

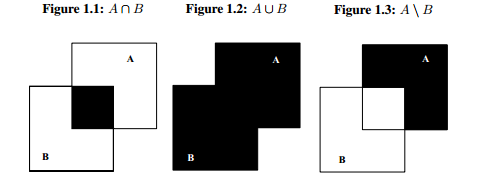

A convenient pictorial representation of the operations defined above are the Venn diagrams, shown in Fig. 1.1 – 1.3 on the following page: The shaded area represents

the result of the respective operation.

Lemma 1. 1. Let A ⊆ U; then

A ∩ A = A, A ∪ A = A.

2. A ∩ ∅ = ∅, A ∪ ∅ = A.

3. A ∩ U = A, A ∪ U = U.

4. A ∩ −A = ∅, A ∪ −A = U.

Proof. We shall only show 1. and 2.; the rest is left as an exercise.

1. A ∩ A = {x ∈ U : x ∈ A and x ∈ A} = {x ∈ U : x ∈ A} = A.

A ∪ A = {x : x ∈ A or x ∈ A} = {x : x ∈ A} = A.

2. A ∩ ∅ = {x : x ∈ A and x ∈ ∅}; since ∅ has no elements, the right hand side (and thus the left hand side) of the equation is the empty set.

A ∪ ∅ = {x : x ∈ A or x ∈ ∅}; again, since ∅ has no elements, we do not “add” anything to A, hence, A ∪ ∅ = A.

Lemma 1. 2. If A and B are sets, then A ∩ B = B ∩ A, and A ∪ B = B ∪ A.

This is called the Law of Commutativity for ∩ and ∪.

Proof. We only prove the first part; the second part is similar:

A ∩ B = {x : x ∈ A and x ∈ B} = {x : x ∈ B and x ∈ A} = B ∩ A.

Since we have defined the operations ∩ and ∪ only for two sets, the expressions A ∩ B ∩ C and A ∪ B ∪ C do not make sense. However, if we write (A ∩ B) ∩ C and (A ∪ B)∪ C, then this instruct us first to find the intersection (union) of A and B, and then the intersection (union) of A ∩ B (A ∪ B) with C. On the other hand, we could also have interpreted the line A ∩ (B ∩ C) and A ∪ (B ∪ C), which tells us first to find the intersection (union) of B and C, and then proceed to A. The following Lemma shows that it does not matter what we do first - the result is the same.

Lemma 1. 3. If A,B, C are sets, then

1. (A ∩ B) ∩ C = A ∩ (B ∩ C)

2. (A ∪ B) ∪ C = A ∪ (B ∪ C)

This is called the Law of Associativity for ∩ and ∪.

Proof. We only prove 1. We have to show both inclusions, i.e If x ∈ (A ∩ B) ∩ C, then x ∈ A∩(B ∩C) and vice versa. “⊆”: Let x ∈ (A∩B)∩C; then, x ∈ A∩B and x ∈ C; since x is an element of A ∩ B, we obtain that x ∈ A and x ∈ B. Thus we have x ∈ A and x ∈ B and x ∈ C, which implies x ∈ A ∩ (B ∩ C).

The previous Lemma enables us to give a meaningful interpretation to expressions like A∩B∩C or A∪B∪C, e.g A∪B∪C = {x : x ∈ A or x ∈ B or x ∈ C}, and we shall omit the brackets where no confusion can arise. The law of associativity also allows us to consider more than three sets by grouping the sets in a convenient way.

الاكثر قراءة في نظرية المجموعات

الاكثر قراءة في نظرية المجموعات

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)