Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

The nature of the linguistic sign

المؤلف:

David Hornsby

المصدر:

Linguistics A complete introduction

الجزء والصفحة:

47-3

2023-12-12

2040

The nature of the linguistic sign

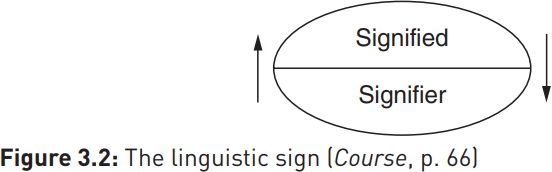

Saussure defines language as a system of signs, his conception of which takes up much of Part I of the Course. The sign for Saussure consists of two elements: a signifier (signifiant) and a signified (signifié), both of which are arbitrary. The arbitrariness of the signifier is not a difficult concept to grasp. As a native speaker of English, when I see an animal barking I call it a dog, but there is no reason why it should be called a dog: if there were, all languages would have discovered this and given this animal the same name, rather than selecting such different terms as ci (Welsh), perro (Spanish), Hund (German) or mbwa (Swahili).

The absence of any link between the word and its referent in the real world is almost universal, the one class of exceptions being onomatopoeic words, where a word echoes a sound associated with the referent in question, as for example in cuckoo. Even for onomatopoeic words, however, there is a large measure of arbitrariness: cuckoos are called ‘cuckoos’ only in English, and to return to our canine example above, there is a remarkable divergence cross-linguistically even in the way barking is represented in print: English dogs go woof! woof! while French ones go ouah! ouah! and Russian ones gav! gav! in spite of the fact that there are no linguistic differences (to the best of our knowledge) between dogs of different nationalities. (This observation has spawned a number of websites and even a Wikipedia page, which you may like to check out for yourself.)

The arbitrariness of the signifier, however, is only part of the story: Saussure stresses that the signified too is arbitrary, as each language divides up the world in its own way. A consequence of the conceptual arbitrariness of the signified is that precise translation between languages often proves impossible. Swedish, for example, has no single word for grandmother, making a distinction between mormor (‘mother mother’) and farmor (‘father mother’), which English does not. Some concepts seem to elude translation altogether and, even concepts as familiar as color terms turn out to be highly language-specific. A second consequence of arbitrariness is that both signifier and signified are subject to change: the silent letters of know or though in English attest to a time when the pronunciation of both words was different; Old English þing once meant ‘discussion’ but came to mean thing, while the word man originally meant ‘person’ but acquired the meaning ‘male person’, an etymology which leads some people to object to terms such as chairman as gender-exclusive.

Synchronic v diachronic

Saussure insisted on the separation of synchronic facts (describing the language at a particular point in time) from diachronic ones (relating to changes which have taken place in the language), on the grounds that a native speaker does not need to know the history of his/her language to speak and understand it.

While the study of language change, a major preoccupation of the nineteenth-century comparative philologists, is of interest and value in itself, Saussure warned against confusing synchronic approaches (studying the language as a system at a single point in time) and diachronic ones (focusing on changes in the language system). Saussure accorded priority to the former, using a chess analogy to distinguish the two perspectives.

For Saussure, Grimm had failed to distinguish between diachronic changes and the functions given to new elements in the resulting language system. Thus the vowel alternations foot: feet; goose: geese; tooth: teeth emerged as the result of a purely phonetic change which was used by the system to designate singular and plural: it did not happen in order to represent the plural, as if ‘plural’ were a slot to be filled and the language developed a new form in order to fill it. Sound changes are ‘blind’ but have consequences for the system as a whole: for example, the change in British English which saw the wh-sound [ʍ] pronounced like [w] had the consequence that such word pairs as which/witch, whales/Wales and while/wile are no longer distinguished by most British English speakers.

Saussure and chess

On two occasions in the Course, Saussure likens language to a game of chess. Highlighting the difference between synchrony and diachrony, he invites the reader to imagine a game in progress, and notes that a person who recalls the moves that led to the current state of play has no advantage, in playing the game, over a person who has turned up in the last two minutes. In the same way, a speaker does not need to know about previous states of his/her mother tongue to speak it fluently. Saussure suggests, however (Course, p. 89), that the analogy breaks down in one important respect: while chess moves result from the volition of a player trying to secure a win, no such teleology, or change directed towards a particular outcome, is at work in the case of language change. In Saussure’s words, ‘language premeditates nothing’.

In another chess analogy, Saussure points out that the different chess pieces in themselves are unimportant: it matters little if the two rooks or bishops are not of identical shape, provided they are sufficiently different from other pieces to be distinguished from them. If, say, the knight were lost, he says, ‘even a figure shorn of any resemblance to a knight can be declared identical provided the same value is attributed to it’ (p. 110). In fact, a problem would only arise if the figure chosen were insufficiently different from another piece – say, a bishop – to be distinguished from it, in which case the game would be fundamentally altered.

Saussure also stated, famously, that ‘language is form, not substance’, and that language is a system of relations with no positive terms, only differences. To understand Saussure’s insights here, it is worth dwelling on these claims, both of which stem from our earlier principle of the arbitrariness of the sign:

To illuminate the notion of linguistic entities without an essence of their own, Saussure asks us to consider a railway timetable. We are prepared to accept, he says, that the 8.25 Geneva to Paris express which leaves each day is ‘the same train’ in spite of the fact that its coaches, driver and locomotive are probably not the same each day: we would continue to call it the ‘8.25 Geneva to Paris’ train even if it left a few minutes late now and again. We do so because the inherent qualities of the train itself do not matter: what matters is the fact that this train is not the 10.25 to Paris, or the 8.25 to Bern.

Saussure’s concept of linguistic values is based on differences: if we wish to learn the meaning of the word blue we need to know how it differs from red, green, yellow, etc.: there is no inherent concept of ‘blueness’ which will leap out at us and enable us to understand the concept. Similarly, we can only understand dog by virtue of its contrast with cat, horse, elephant, etc., without which dog would mean little more than animal. The importance of difference is even clearer in the case of speech sounds. There will almost certainly be slight differences each time we produce a b sound in a word like bit, and differences again between our own pronunciation and that of others. Yet all these different realizations will be recognized by English speakers as ‘the same’, in the same way that a teacher will recognize the many different handwritten b’s he/she might see in 30 Year 6 homework assignments as ‘the same letter’. It matters not if a Year 6 child occasionally puts a smiley in the round part of the ‘b’, gives it a moustache or draws sunglasses on the stalk: it will remain recognizably b unless and until it ceases to be distinct from other letters and starts to be confused with, say, d, with the result that the pairs bid/did, bad/dad, big/dig and so on are no longer distinguishable.

If in language ‘there are only differences’, then it is the relations between elements in the system, rather than the elements themselves, which are meaningful, and Saussure suggests that these relations are of two kinds. The first, syntagmatic relations, represent the combinatorial possibilities a language permits: adjectives may qualify nouns in English, for example (a green coat) but not verbs (*to green try); adverbs may qualify verbs (go boldly/boldly go) but not nouns (*boldly tree/*tree boldly).

Paradigmatic relations, by contrast, concern the range of elements that can be substituted in the same environment. For example, in the sentence John built a house we could replace John with another proper noun such as Peter or Mary, by a noun phrase such as the little old man or (in a fictional parallel universe) the giant slug in evening dress. Similarly, we could replace built with build, constructed, destroys, is destroying, admires and so on. At the phonological level, the first sound /p/ of pit stands in opposition to all the other sounds which could replace it to produce other words, e.g. kit, sit, mitt, fit, lit, nit.

A final important dichotomy for Saussure was that of langue and parole, meaning respectively the abstract language system and the concrete instantiation of that system in speech. For Saussure, the real object of study for the linguist was langue, but our only access to it is via parole, with all its hesitations, slips of the tongue, false starts and so on. He saw the difference between the two exemplified in the contrast between phonetics, the study and description of speech sounds, and phonology, the study of sound systems in language. Strongly influenced by the sociologist Emile Durkheim, Saussure saw langue as a social phenomenon, implanted in the individual, who may through his/her own parole initiate or adopt change in langue.

The language system

Langue (the language system) is based on relations of two kinds:

syntagmatic, or combinatorial relations between elements

paradigmatic relations, involving items of the same category which can be substituted for each other in a given environment.

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

الاكثر قراءة في Linguistics fields

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)