Quotatives and idioms

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

244-7

الجزء والصفحة:

244-7

21-1-2023

21-1-2023

2267

2267

Quotatives and idioms

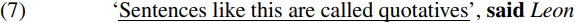

An interesting piece of evidence in support of the VP-Internal Subject Hypothesis comes from quotative inversion structures like (7) below:

The relevant structures are called quotative because they involve a direct quotation (the underlined quoted material being enclosed within inverted commas); they involve inversion in the sense that the bold-printed main verb said in (7) ends up positioned in front of its italicized subject Leon. Collins (1997), Collins and Branigan (1997) and Su˜ner (2000) argue that the italicized subject in such structures remains in situ in the specifier position within the verb phrase, and that the bold-printed verb moves to some higher head position above the VP in which it originates.

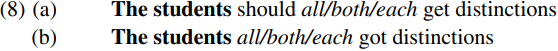

But what evidence is there that the subject remains in spec-VP in quotative inversion structures like (7)? Part of the evidence comes from the syntax of floating quantifiers. In structures in which the subject raises out of spec-VP into spec-TP in English, the moved subject in spec-TP can serve as the antecedent for a floating quantifier like all/both/each (i.e. for a quantifier which is positioned after the subject and forms a separate constituent, but is nonetheless interpreted as modifying the subject). We can illustrate this in terms of structures like (8) below:

In (8a) the bold-printed subject DP the students is in spec-TP and hence precedes the auxiliary should. The italicized floating quantifiers all/both/each are c-commanded by the subject DP the students, and are construed as modifying the subject DP. Hence, examples like (8a) tell us that a moved subject in spec-TP can serve as the antecedent of a floating quantifier positioned between the moved subject and the verb. By hypothesis, the bold-printed subject is likewise in spec TP in (8b) and so can again occur as the antecedent of the italicized quantifier between the moved subject and the verb.

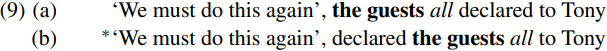

In the light of this restriction, consider the following contrast (noted by Collins and Branigan 1997):

In the uninverted structure (9a), the subject the guests occupies the canonical spec-TP position associated with subjects, and hence can serve as the antecedent of the floating quantifier all. Now, if the subject were also in spec-TP in (9b), we’d again expect the quantifier all to be able to be positioned after the subject. The fact that this is not possible leads Collins and Branigan to conclude that the subject in quotative inversion structures like (9b) remains in situ in spec-VP. If so, this provides empirical evidence in support of VPISH.

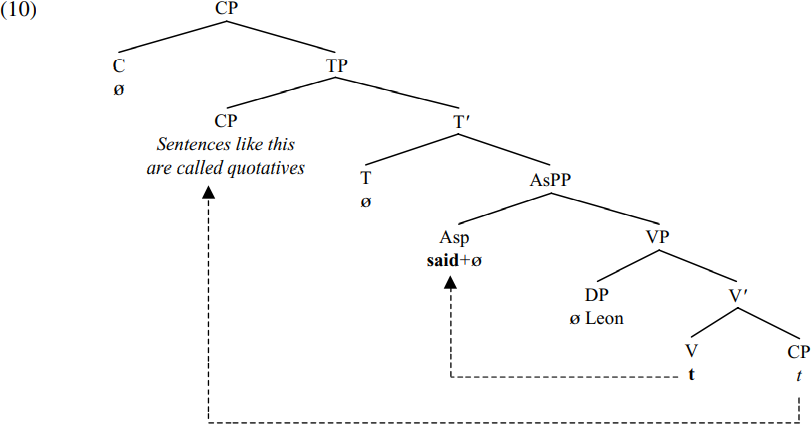

However, the assumption that the postverbal subject in quotative inversion structures like (7) and (9b) remains in situ in spec-VP raises the question of where the verb and the quoted material (both of which end up in front of the subject) move to, since if they remained in situ within the verb phrase, they would be expected to follow the subject. Collins (1997) argues that the quoted material moves to spec-TP (a position which is normally occupied by the subject, but which is available for some other constituent to move into if the subject remains in spec-VP). As for where the verb moves to, Su˜ner (2000) argues that it does not move to T (since T is not strong enough to attract main verbs to move to T in present-day English), but rather moves to the head Asp (= Aspect) position of an AspP (= Aspect Phrase) projection which is positioned below T but above VP. On this view, a sentence like (7) would have the structure (10) below (with arrows showing movement, and t indicating trace copies of moved constituents):

Su˜ner notes that an interesting prediction made by the assumption that the verb undergoes short verb movement to Asp (rather than long verb movement to T) is that inversion of verb and subject will be blocked in structures containing an aspectual auxiliary like perfect have or progressive be, and she notes that contrasts like that in (11) below provide empirical support for her claim:

If finite aspectual auxiliaries originate in Asp and raise to T, was will originate in Asp in structures like (11) and hence will block movement of the verb asking to Asp – so accounting for the ungrammaticality of quotative inversion in structures like (11b,c). (See Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 2001 for discussion of other subject-in-situ structures.)

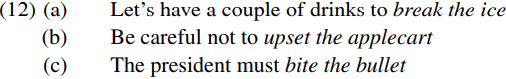

Further empirical evidence in support of the VP-Internal Subject Hypothesis comes from the syntax of idioms. We can define idioms as expressions (like those italicized below) which have an idiosyncratic meaning which is not a purely compositional function of the meaning of their individual parts:

There seems to be a constraint that only a string of words which forms a unitary constituent can be an idiom. So, while we find idioms like those in (12) which are of the form verb+complement(but where the subject isn’t part of the idiom), we don’t find idioms of the form subject+verb where the verb has a complement which isn’t part of the idiom: this is because in subject+verb+complement structures, the verb and its complement form a unitary constituent (a V-bar), whereas the subject and the verb do not – and only unitary constituents can be idioms.

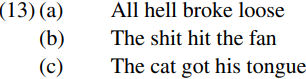

In the light of the constraint that an idiom is a unitary constituent with an idiosyncratic interpretation, consider idioms such as the following:

In (13), not only is the choice of verb and complement fixed, but so too is the choice of subject. In such idioms, we can’t replace the subject, verb or complement by near synonyms – as we see from the fact that sentences like (14) below are ungrammatical (on the intended idiomatic interpretation):

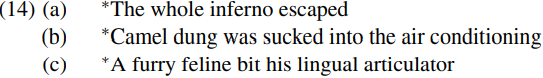

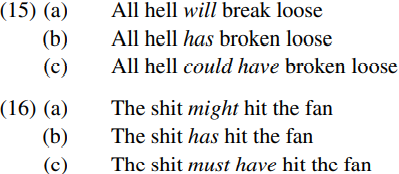

However, what is puzzling about idioms like (13) is that one or more auxiliaries can freely be positioned between the subject and verb:

How can we reconcile our earlier claim that only a string of words which form a unitary constituent can constitute an idiom with the fact that all hell . . . break loose is a discontinuous string in (15), since the subject all hell and the predicate break loose are separated by the intervening auxiliaries will/has/could have? To put the question another way: how can we account for the fact that although the choice of subject, verb and complement is fixed, the choice of auxiliary is not?

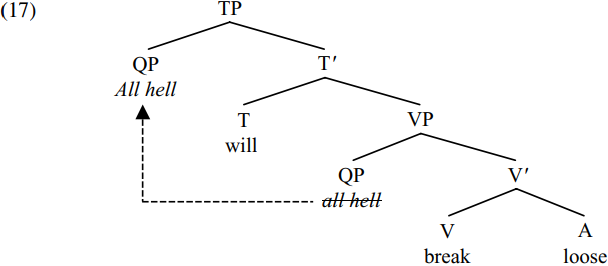

The VP-Internal Subject Hypothesis provides a straightforward answer, if we suppose that subjects originate internally within VP, and that clausal idioms like those in (13) are VP idioms which require a fixed choice of head, complement and specifier in the VP containing them. For instance, in the case of (13a), the relevant VP idiom requires the specific word break as its head verb, the specific adjective loose as its complement, and the specific quantifier phrase all hell as its subject/specifier. We can then account for the fact that all hell surfaces in front of the auxiliary will in (15a) by positing that the QP all hell originates in spec-VP as the subject of break loose, and is then raised (via A-movement) into spec-TP to become the subject of will break loose. Given these assumptions, (15a) will be derived as follows. The verb break merges with the adjective loose to form the idiomatic V-bar break loose. This is then merged with its QP subject all hell to form the idiomatic VP all hell break loose. The resulting VP is merged with the tense auxiliary will to form the T-bar will all hell break loose. Since finite auxiliaries carry an [EPP] feature requiring them to have a subject specifier with person/number features, the subject all hell moves from being the subject of break to becoming the subject of will – as shown in simplified form in (17) below:

We can then say that (in the relevant idiom) all hell must be the sister of break loose, and that this condition will be met only if all hell originates in spec-VP as the subject (and sister) of the V-bar break loose. We can account for how the subject all hell comes to be separated from its predicate break loose by positing that subjects originate internally within VP and from there raise to spec-TP (via A-movement) across an intervening T constituent like will, so that the subject and predicate thereby come to be separated from each other – movement of the subject to spec-TP being driven by an [EPP]feature carried by [T will]requiring will to have a subject with person/number features. Subsequently, the TP in (17) is merged with a null declarative complementizer, so deriving the structure associated with (15a) All hell will break loose.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة