Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

That-relatives

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

228-6

19-1-2023

2049

That-relatives

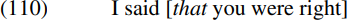

A type of relative clause which we have not so far looked at are that-relatives (i.e. relative clauses introduced by that) like those bracketed below:

What’s the status of that in such clauses? One answer (suggested by Sag 1997) is that the word that is a relative pronoun which behaves in much the same way as other relative pronouns like who and which. However, an alternative analysis which we will adopt here is to take that to be a relative clause complementizer (= C). The C analysis accounts for several properties of relative that. Firstly, it is homophonous with the complementizer that found in declarative clauses like that bracketed in:

and has the same phonetically reduced exponent /ðət/. Secondly, (unlike a typical wh-pronoun) it can only occur in finite relative clauses like those bracketed in (109) above, not in infinitival relative clauses like those bracketed below:

Thirdly, unlike a typical wh-pronoun such as who (which has the formal-style accusative form whom and the genitive form whose), relative that is invariable and has no variant case forms – e.g. it lacks the genitive form that’s in standard varieties of English, as we see from (112) below:

Thirdly, unlike a typical wh-pronoun such as who (which has the formal-style accusative form whom and the genitive form whose), relative that is invariable and has no variant case forms – e.g. it lacks the genitive form that’s in standard varieties of English, as we see from (112) below:

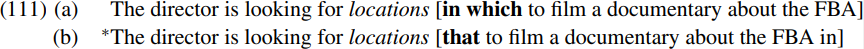

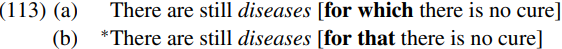

Fourthly, unlike a typical wh-pronoun, that does not allow pied-piping of a preposition:

Observations such as these suggest that relative that is a complementizer rather than a relative pronoun. If so, that-relative clauses will be headed by an overt complementizer in the same way as infinitival relative clauses containing the transitive complementizer for in sentences such as (99–103) above.

However, given the assumption that all relative clauses contain a relative pronoun, it is plausible to conclude that relative clauses headed by that contain a relative pronoun which moves to spec-CP and which is ultimately given a null spellout in the PF component. The analysis of relative clause that as a complementizer which attracts a wh-pronoun to become its specifier is lent some plausibility by the fact that in earlier varieties of English we found relative clauses containing an overt (preposed) wh-pronoun followed by the complementizer that – as the following examples illustrate:

Moreover, we have syntactic evidence from island constraints in support of analyzing that-relatives in present-day English as involving movement of a relative pronoun to spec-CP. For example, relative clauses containing that show the same wh-island sensitivity as relative clauses containing an overt wh-pronoun like who:

This parallelism suggests that the derivation of that-relatives involves a relative pronoun moving to the spec-CP position within the relative clause and subsequently being given a null spellout at PF, with the ungrammaticality of (115a,b) being attributed to the fact that the relative pronoun originates as the complement of the preposition to and is extracted out of the bracketed what-clause in violation of the wh-island constraint.

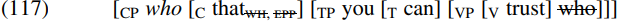

This being so, the bracketed relative clause in (109a) It’s hard to find people [that you can trust] will involve merging a relative pronoun like who as the object of the verb trust, so that the relative clause has the structure shown below at the point where the complementizer that is merged with its TP complement:

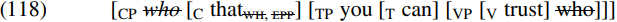

The [WH, EPP]features of the complementizer that will attract the relative pronoun who to become the specifier of that and are thereby deleted (along with the trace copy of the moved pronoun who), so deriving the CP (117) below:

The spellout condition (107) will allow the relative pronoun to be given a null spellout in the PF component, so deriving:

and (118) is the structure of the bracketed relative clause in (109a).

However, an important complication arises at this point. After all, our Relative Pronoun Spellout Condition/RPSC (107) tells us that a relative pronoun is optionally given a null spellout in a finite clause. So, while we would expect a structure like (118) in which the relative pronoun has a null spellout to be grammatical, we would also expect a structure like (117) in which the relative pronoun is overtly spelled out as who to be grammatical. It might at first sight seem as if we can get round this problem by modifying RPSC so as to specify that a relative pronoun is obligatorily given a null spellout in a relative clause headed by the complementizer that. However, this will not account for the fact that relative clauses headed by that are also ungrammatical if other material is pied-piped along with the relative pronoun:

And indeed, the same is true of infinitival relative clauses headed by the complementizer for:

Why should sentences like (119) and (120) be ungrammatical?

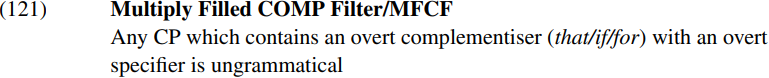

The answer given to this question by Chomsky and Lasnik (1977) is that such sentences violate a constraint operating in present-day English they call the Multiply Filled COMP Filter/MFCF, and which we can outline informally as follows:

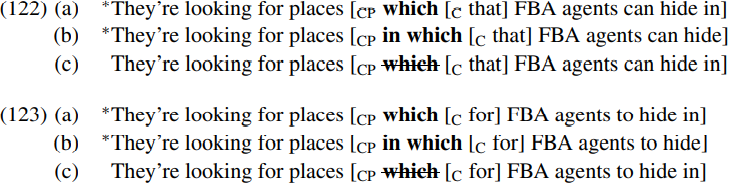

The relevant ‘filter’ is arguably reducible to a lexical property of overt complementizers (namely that they don’t allow an overt specifier). Be that as it may, MFCF helps us account for contrasts such as the following in present-day English:

Sentences like (122a,b) and (123a,b) violate MFCF because they contain an overt wh-expression (which or in which) which serves as the specifier of an overt complementizer (that or for): (123b) is also ruled out by the spellout condition (107) which requires a relative pronoun which occupies the specifier position in a non-finite relative clause to have a null spellout. By contrast, (122c) and (123c) involve no violation of MFCF because they contain a null relative pronoun which serves as the specifier of an overt complementizer.

In some varieties of English, MFCF seems to have a rather different form, permitting wh+that clauses like that bracketed (124a) below, but not those like that bracketed in (124b):

As noted by Zwicky (2002), the relevant varieties permit wh+that structures when the wh-expression is a wh-phrase like what kind of plan, but not when it is a wh-pronoun like what. Such varieties seem to have a somewhat different version of MFCF from that which operates in Standard English.

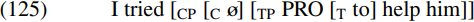

Since our discussion has made much use of null relative pronouns, it is interesting to explore the question of whether there are parallels between these and other null pronouns – e.g. null subject pronouns like ‘big PRO’ and ‘little pro’. The answer seems to be that there are indeed potential parallels. For example, we claimed that in a control clause like that bracketed below:

the null complementizer [C ø] in the bracketed control clause obligatorily assigns null case to the subject of its TP complement. What this means is that the only type of subject which TP permits in a control clause is a null ‘big PRO’ subject. Let’s suppose that just as the complementizer in a control clause requires the null spellout of a constituent which it case-marks (with the result that the only kind of subject allowed in a control clause is PRO), so too an overt relative clause complementizer like for/that requires the null spellout of the wh-marked constituent which it attracts (with the result that relative clauses headed by for/that must contain a null relative pronoun). This assumption would account for the pattern of data found in for/that relative clauses like those bracketed in (122) and (123) above.

But what about relative clauses headed by a null infinitival complementizer? Here the distribution of null relative pronouns seems more akin to that of ‘little pro’ subjects in a null-subject language like Italian. In Italian, the subject of a finite clause is only null if it is a weak pronoun (e.g. one which is not focused or used contrastively), not if it is a DP like il presidente della repubblica ‘the president of the republic’ or Maria: hence, we find both overt and null subjects in finite clauses in Italian. If we suppose that relative pronouns are weak (as seems plausible since they cannot carry contrastive stress), we can draw a parallel between pro subjects in a null-subject language and English relative pronouns in a relative clause introduced by a null infinitival complementizer: if the wh-moved expression in the relative clause comprises a relative pronoun on its own (as in structures like (108a,b) above), it must obligatorily be given a null spellout (in the same way as a weak subject pronoun in a finite clause in Italian must be given a null spellout). But if the moved wh-expression is a larger structure (e.g. a PP comprising a preposition and a relative pronoun as in 108c,d), the wh-expression cannot be given a null spellout (in the same way as a DP subject like il presidente della repubblica ‘the president of the republic’ in a finite clause in Italian cannot be given a null spellout).

Finally, consider finite relative clauses headed by a null complementizer like those in (104a,b) and (105a,b) above, where a relative pronoun in spec-CP optionally receives a null spellout. There seem to be wider parallels here with the phenomenon of Topic Drop in finite clauses in languages like German. In German, an expression which is the topic of a sentence can be moved into the specifier position within CP (with concomitant movement of an auxiliary or non-auxiliary verb into C) and can optionally be given a null spellout if it is a pronoun – as we see from the optionality of the pronominal topic das ‘that’ in structures like that below (from Rizzi 1992, p. 105):

If the preposed pronominal topic das‘that’ in (126) occupies spec-CP position, the conditions under which it optionally receives a null spellout can be assimilated to those under which a relative pronoun in spec-CP optionally receives a null spellout in a finite clause headed by a null complementizer in English. Of course, important theoretical questions remain about how and why certain types of pronoun in spec-CP in certain types of clause receive a null spellout – but we shall not pursue these here. And the null spellout of whether in root main clauses may be a related phenomenon, given the observation by Rizzi (2000) that (in some languages) the specifier of a root clause can have a null spellout in certain types of structure.

A final descriptive detail which should be noted is that our discussion of relative clauses has concentrated on restrictive relative clauses, so called because in a sentence such as:

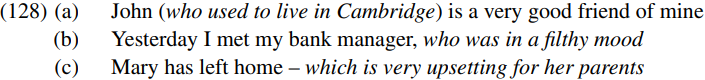

the bracketed relative clause restricts the class of men being referred to in the sentence to the one who they arrested. A different type of relative clause are appositive relative clauses like those italicized below:

They generally serve as ‘parenthetical comments’ or ‘afterthoughts’ set off in a separate intonation group from the rest of the sentence in the spoken language (this being marked by parentheses, or a comma, or a hyphen in the written language). Unlike restrictive, appositives can be used to qualify unmodified proper nouns (i.e. proper nouns like John which are not modified by a determiner like the). Moreover, they are always introduced by an overt relative pronoun, as we see in relation to the parenthesized appositive relative clauses below:

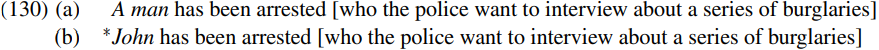

Furthermore, whereas a restrictive relative clause like that bracketed in (130a) below can be extraposed (i.e. moved) to the end of the containing clause and thereby be separated from its italicized antecedent, an appositive relative clause like that bracketed in (130b) does not allow extraposition:

A third type of relative clause are so-called free relative clauses such as those italicized in:

A third type of relative clause are so-called free relative clauses such as those italicized in:

They are characterized by the fact that the wh-pronoun what/where/how appears to be antecedentless, in that it doesn’t refer back to any other constituent in the sentence. Moreover, the set of relative pronouns found in free relative clauses is different from that found in restrictives or appositives: e.g. what and how can serve as free relative pronouns, but not as appositive or restrictive relative pronouns; and conversely which can serve as a restrictive or appositive relative pronoun but not as a free relative pronoun. Appositive relatives (discussed in Citko 2002) and free relatives are interesting in their own right, but we shall not attempt to explore their syntax here.

Although there are many interesting aspects of relative clauses which we will not go into here, the brief outline given suffices for the purpose of underlining that it is not only interrogative wh-expressions which undergo wh-movement, but also exclamative wh-expressions and relative wh-expressions (with the latter showing null spellout of a wh-pronoun in certain types of relative clause). Indeed, there are a range of other constructions which have been claimed to involve wh-movement of a null wh-operator, including comparative clauses like (132a) below, as-clauses like (132b), and so-called tough-clauses like (132c):

It is interesting to note that (132a) has a variant form containing the overt wh-word what in some (non-standard) varieties of English, where we find It is bigger than what I expected it to be: see Kennedy and Merchant (2000), Lechner (2001) and Kennedy (2002) for discussion of comparative structures; see also Potts (2002) for discussion of as-structures like (132b). We will not attempt to fathom the syntax of constructions like those in (132) here, however

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)