Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Wh-movement, EPP and the Attract Closest Principle

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

197-6

5/12/2022

3992

Wh-movement, EPP and the Attract Closest Principle

An important question raised by the analysis outlined above is what triggers wh-movement. Chomsky (1998, 1999, 2001) suggests that an [EPP] feature is the mechanism which drives movement of wh-expressions to spec-CP. More specifically, he maintains that just as T in finite clauses carries an [EPP] feature requiring it to be extended into a TP projection containing a subject as its specifier, so too C in wh-questions carries an [EPP] feature requiring it to be extended into a CP projection containing a wh-expression as its specifier. Some evidence that complementizers can indeed have an [EPP] feature comes from sentences like (25b) below:

If we suppose that expletive there is inserted in a sentence like (25a) in order to satisfy an [EPP] feature carried by T, and if we further suppose (in the light of arguments offered by Landau 2002) that from is a complementizer in structures like (25b), it seems plausible to suppose that there is used in (25b) to satisfy an [EPP] feature carried by the complementizer from. More generally, the [EPP] feature of a head H requires H to have a specifier which matches one or more of the features carried by H: so, for example, since a finite T carries person and number features, its [EPP] feature requires it to have a subject with matching person and/or number features; and if we assume that C in a wh-clause contains a [WH] feature, this will mean that its [EPP] feature requires it to have a wh-specifier

We can illustrate how the EPP analysis of wh-movement works by looking at the derivation of the bracketed interrogative complement clause in (26) below:

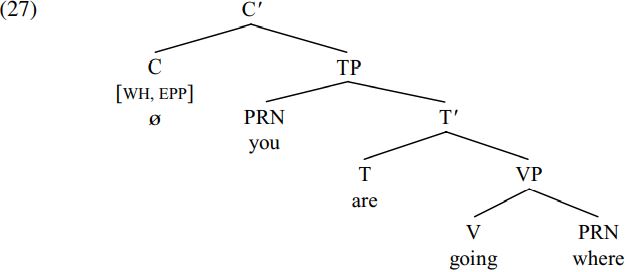

The bracketed wh-question clause in (26) is derived as follows. The verb going is merged with its complement where (which is a locative adverbial pronoun) to form the VP going where. The present-tense auxiliary are is then merged with the resulting VP to form the T-bar are going where. The pronoun you is in turn merged with this T-bar to form the TP you are going where. A null complementizer [C ø] is subsequently merged with the resulting TP. Since the relevant clause is a wh-question, C contains a [WH] feature. In addition, since English (unlike Chinese) is the kind of language which requires wh-movement in ordinary wh-questions, C also has an [EPP] feature requiring it to have a specifier. Given these assumptions, merging C with its TP complement will form the C-bar in (27) below (where features are CAPITALIZED and enclosed within square brackets):

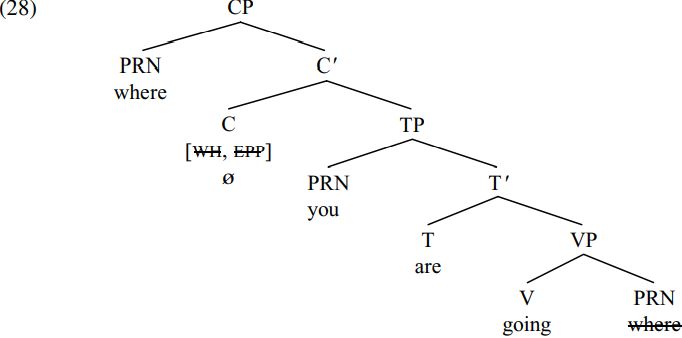

(A minor descriptive detail is that the locative adverbial pronoun where is categorized here as a PRN/pronoun, though it could equally be assigned to the category ADV/adverb.) The [WH] feature of C allows C to attract a wh-expression. The [EPP] feature of C requires C to project as its specifier an expression which has a feature which matches some feature of C: since C carries a [WH] feature, this amounts to a requirement that C must project a wh-specifier. On the assumption that the wh-pronoun where carries a [WH] feature, this means that C will attract the wh-pronoun where to move from the VP-complement position which it occupies in (27) above to CP-specifier position. If we suppose that the [WH] and [EPP] features carried by C are deleted (and thereby inactivated) once their requirements are satisfied (deletion being indicated by strikethrough), we derive the structure (28) below (assuming, too, that the phonological features of the trace of the moved wh-constituent where are also deleted):

There is no auxiliary inversion (hence no movement of the auxiliary are from T to C) because (28) is a complement clause, and an interrogative C only carries a [TNS] feature triggering auxiliary inversion in main clauses.

Chomsky (2001) maintains that movement is simply another form of merger. He refers to merger operations which involve taking an item out of the lexical array and merging it with some other constituent as external merge, and to movement operations by which an item contained within an existing structure is moved to a new position as internal merge. Accordingly, the structure (27) is created by a series of external merger operations, and is then mapped into (28) by an internal merger operation (namely wh-movement).

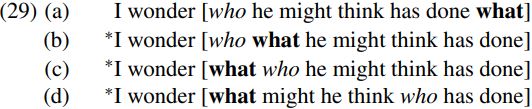

The EPP analysis of wh-movement has interesting implications for the syntax of multiple wh-questions which contain two or more separate wh-expressions. (See Dayal 2002 for discussion of the semantic properties of such questions.) A salient syntactic property of such questions in English is that only one of the wh-expressions can be preposed – as we see from the fact that in the bracketed interrogative clauses in (29) below, only who can be preposed and not what:

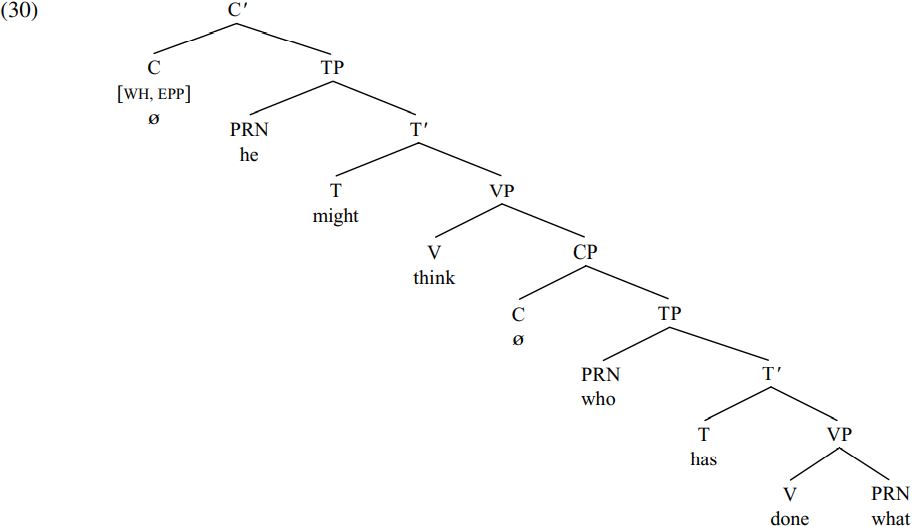

In order to get a clearer picture of what is going on in the bracketed complement clause here, let’s consider what happens when we arrive at the stage of derivation shown in (30) below:

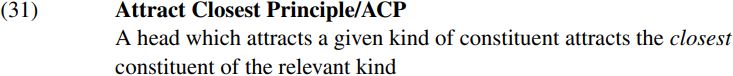

By hypothesis, the null complementizer [C ø] at the root/top of the tree contains a [WH] feature requiring the clause to contain a wh-expression, and an [EPP] feature requiring it to have a specifier matching the [WH] feature carried by C (i.e. to have a wh-specifier). In order to satisfy this requirement, C searches for a wh-expression within the C-bar structure immediately containing it in (30). Since it is who rather than what which is preposed in (30) and since who is closer to C than what, let’s suppose that C attracts the closest wh-expression which it c-commands. This requirement is a consequence of a principle of Universal Grammar (adapted from Chomsky 1995, p. 297) which we can outline informally as follows:

(Chomsky 1995, p. 311 proposes an analogous principle which he terms the Minimal Link Condition and formulates it thus: ‘K attracts  only if there is no

only if there is no  closer to K than

closer to K than  , such that K attracts

, such that K attracts  .’) It follows from ACP that a C carrying [WH, EPP] features will trigger movement of the closest constituent carrying a wh-feature to C. So, since who appears to be closer to C than what in (30), it is who which is attracted to move to spec-CP. Using rather different but equivalent terminology, sentences like (29) can be said to show a superiority effect in that C has to attract the ‘highest’ constituent of the relevant type. An alternative to the ACP account is to suppose that the relevant effect is a consequence of an Intervention Constraint to the effect that in a structure of the form [. . . X . . . [. . . Y . . . [. . . Z . . .]]] X cannot attract Z if there is a constituent Y of the same type as Z which intervenes between X and Z: on this view, the presence of who intervening between C and what in (30) prevents C from attracting what to move to spec-CP.

.’) It follows from ACP that a C carrying [WH, EPP] features will trigger movement of the closest constituent carrying a wh-feature to C. So, since who appears to be closer to C than what in (30), it is who which is attracted to move to spec-CP. Using rather different but equivalent terminology, sentences like (29) can be said to show a superiority effect in that C has to attract the ‘highest’ constituent of the relevant type. An alternative to the ACP account is to suppose that the relevant effect is a consequence of an Intervention Constraint to the effect that in a structure of the form [. . . X . . . [. . . Y . . . [. . . Z . . .]]] X cannot attract Z if there is a constituent Y of the same type as Z which intervenes between X and Z: on this view, the presence of who intervening between C and what in (30) prevents C from attracting what to move to spec-CP.

One question this raises, however, is how we determine whether who or what is closer to C. At first sight, it might seem as if there is a simple way of doing this – namely by counting the number of nodes you have to go through if you try and get from one constituent to the other by climbing along the branches of the tree. In order to get from the C node containing the null complementizer to the PRN node containing who, we have to go through six other nodes (C-bar, TP, T-bar, VP, CP, TP), whereas in order to get from C to the PRN node containing what we have to go through eight other nodes (C-bar, TP, T-bar, VP, CP, TP, T-bar, VP): hence, this simple node-counting procedure tells us that who is closer to C than what, and consequently it is who which is attracted by C in (30) and not what, in accordance with the Attract Closest Principle.

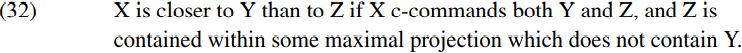

However, the idea that grammars might employ a counting algorithm of some kind in order to determine how syntactic operations apply is implausible, since counting otherwise seems to play no part in syntax – for instance, we find no syntactic operations which target (e.g.) the fourth constituent in a sentence, or which invert the second and third constituents. Moreover, the notion of counting is alien to the spirit of Minimalism, which assumes that the only primitive relations in syntax are structural relations like contain and c-command which come about via merger. From a theoretical perspective, it is therefore preferable to define relative closeness in terms of structural relations. There are a variety of ways of doing this (see Fitzpatrick 2002), but for present purposes we can make the following assumption (where X, Y and Z are three different constituents):

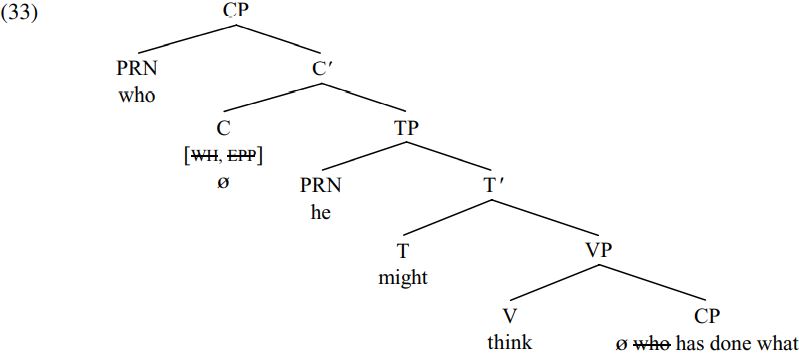

If we take X to be the main clause C in (30), Y to be who and Z to be what, we can see that who is closer to the main-clause C than what in terms of the definition of closeness in (32) because C c-commands both who and what but what is contained within a maximal projection (= the VP done what) which does not contain who. In consequence, the Attract Closest Principle (31) correctly predicts that what cannot undergo wh-movement in (30), but who can, with who thereby moving into spec-CP and deriving the structure shown below (assuming deletion of the [WH] and [EPP] features of C, and of the trace copy of the moved pronoun who):

In short, the assumption that C carries [WH] and [EPP]features, in conjunction with the Attract Closest Principle (31) and the ancillary assumption that the [EPP] and [WH] features of C are deleted (and thereby inactivated) once a wh-expression has been moved to spec-CP, accounts for the pattern of grammaticality found in multiple wh-questions like (29). (Note that our focus on English here means that we do not deal with languages like Bulgarian which allow multiple wh-fronting: see Grewendorf 2001 and Boˇskovi´c 2002a for alternative accounts of multiple wh-fronting.)

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)