Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Clauses

Part of Speech

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Wh-movement as a copying operation

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

190-6

5/12/2022

9737

Wh-movement as a copying operation

A tacit assumption made in our analysis of wh-movement in (4) is that just as a moved head (e.g. an inverted auxiliary) leaves behind a null copy of itself in the position out of which it moves, so too a moved wh-expression leaves behind a copy at its extraction site (i.e. in the position out of which it is extracted/moved). In earlier work in the 1970s and 1980s, moved constituents were said to leave behind a trace in the positions out of which they move (informally denoted as t), and traces of moved nominal constituents were treated as being like pronouns in certain respects. A moved constituent and its trace(s) were together said to form a (movement) chain, with the highest member of the chain (i.e. the moved constituent) being the head of the movement chain, and the lowest trace being the foot of the chain. Within the framework of Chomsky’s more recent copy theory of movement, a trace is taken to be a full copy (rather than a pronominal copy) of a moved constituent. Informally, however, we shall sometimes refer to the null copies left behind by movement as traces or trace copies.

The assumption that moved wh-expressions leave a copy behind can be defended not only on theoretical grounds (in terms of our desire to develop a unified theory of movement in which both minimal and maximal projections leave behind copies when they move), but also on empirical grounds. One such empirical argument comes from a phenomenon known as wanna-contraction. In colloquial English, the sequence want to can sometimes contract to wanna, as in (6) below:

Given the claim made that control infinitive clauses are CPs headed by a null complementizer, the complement clause in (6a) will have the skeletal structure shown in (7) below:

The fact that wanna-contraction is possible in (6b) suggests that neither the intervening null complementizer ø nor the intervening null subject PRO prevents to from cliticising onto want in the phonological component, forming want+to – which is ultimately spelled out as wanta or wanna.

What is of particular interest to us is that (in non-sloppy speech styles) the sequence want to cannot contract to wanna in sentences like:

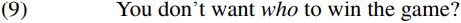

Why should this be? Well, let’s assume that who in (8) originates as the subject of the infinitive clause to win the game – as seems plausible in view of the fact that (8a) has the echo-question counterpart:

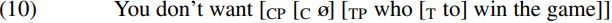

Let’s also assume that the complement of want in structures like (8) and (9) is a CP headed by a null complementizer (perhaps a null variant of for). On this view, (9) will have the skeletal structure (10) below:

Movement of who to the front of the overall sentence (together with auxiliary inversion) will result in the structure shown below (simplified, inter alia, by not showing the trace of the inverted auxiliary):

However, wanna-contraction is not possible in a structure like (11) – as we see from the ungrammaticality of (8b) ∗Who don’t you wanna win the game? Why should this be? This is unlikely to be because of the presence of the null complementizer ø between want and to, since we see from the fact that structures like (7) allow wanna-contraction in sentences like (6b) that wanna-contraction is not blocked by an intervening null complementizer. So what blocks contraction in structures like (11)? The copy theory of movement provides us with a principled answer, if we assume that when who moves to the front of the overall sentence in (11), it leaves behind a copy of itself (which is ultimately given a null phonetic spellout), and it is the presence of this copy intervening between want and to which prevents wanna-contraction in (8b).

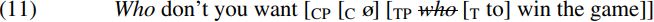

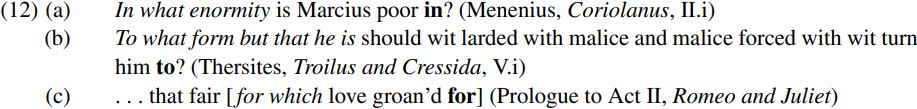

A different kind of evidence in support of the claim that preposed wh-expressions leave behind a null copy when they move comes from a phenomenon which we can call preposition copying. In this connection, consider the following Shakespearean wh-structures:

(12a,b) are interrogative clauses, and the bracketed structure in (12c) is a relative clause – so called because it contains a relative wh-pronoun which relating (more specifically, referring back) to the preceding noun expression that fair. In these examples, an italicized prepositional wh-phrase (i.e. a prepositional phrase containing a wh-word like what/which) has been moved to the front of the relevant clause by wh-movement. But a (bold-printed) copy of the preposition also appears at the end of the clause. In case you think that this is a Shakespearean quirk (or – Heaven forbid – a slip of the quill on the part of Will), the examples in (13) below show much the same thing happening in (bracketed) relative clauses in present-day English:

How can we account for preposition copying in structures like (12) and (13)?

The copy theory of movement enables us to provide a principled answer to this question. Let’s suppose that wh-movement (like head movement) is a composite operation involving two suboperations of copying and deletion: the first stage is for a copy of the moved wh-expression to be moved into spec-CP; the second stage is for the original occurrence of the wh-expression to be deleted. From this perspective, preposition copying arises when the preposition at the original extraction site undergoes copying but not deletion. To see what this means in more concrete terms, consider the syntax of (12a) In what enormity is Marcius poor in? This is derived as follows. The wh-quantifier what merges with the noun enormity to derive the quantifier phrase/QP what enormity. This in turn is merged with the preposition in to form the prepositional phrase/PP in what enormity. This PP is then merged with the adjective poor to form the adjectival phrase/AP poor in what enormity. This AP is merged with the copular verb is to form the verb phrase/VP is poor in what enormity. This VP is merged with a finite T constituent which triggers raising of the verb is from V to T; the resulting T-bar constituent is merged with its subject Marcius (which is a DP headed by a null determiner) to form the tense phrase/TP ø Marcius is poor is in what enormity. Merging this with a strong C into which is moves forms the C-bar Is ø Marcius is poor is in what enormity? Moving a copy of the PP in what enormity into spec-CP in turn derives the structure shown in simplified form in (14) below (with copies of moved constituents shown in italics):

The two italicized copies of the moved copular verb is are deleted by operation of copy-deletion. But consider how copy-deletion affects the copy left behind by movement of the PP in what enormity to spec-CP. If we suppose that copy-deletion in (12a) deletes the smallest phrase containing the wh-word what, it will delete the quantifier phrase what enormity rather than the prepositional phrase in what enormity, so deriving (12a)In what enormity is Marcius poor in?Thus, preposition copying structures like (12) and (13) provide evidence that wh-movement is a composite operation involving wh-copying and wh-deletion.

A related piece of evidence in support of wh-movement involving a copying operation comes from sentences such as those below:

In order to try and understand what’s going on here, let’s take a closer look at the derivation of (15). The expression what hope of finding survivors is a QP comprising the quantifier what and an NP complement which in turn comprises the noun hope and its PP complement of finding survivors. The overall QP what hope of finding survivors is initially merged as the complement of the verb be, but ultimately moves to the front of the overall sentence in (15a): this is unproblematic, since it involves wh-movement of the whole QP. But in (15b), it would seem as if only part of this QP (= the string what hope) undergoes wh-movement, leaving behind the PP of finding survivors. The problem with this is that the string what hope is not a constituent, only a subpart of the overall QP what hope of finding survivors. Given the standard assumption that only complete constituents can undergo movement, we clearly cannot maintain that the non-constituent string what hope gets moved on its own. So how can we account for sentences like (15b)? Copy theory provides us with an answer, if we suppose that wh-movement places a copy of the complete QP what hope of finding survivors at the front of the overall sentence, so deriving the structure shown in skeletal form in (17) below:

If we further suppose that the PP of finding survivors is spelled out in its original position (i.e. in the italicized position it occupied before wh-movement applied) but the remaining constituents of the QP (the quantifier what and the noun hope) are spelled out in the superficial (bold-printed) position in which they end up after wh-movement, (15b) will have the superficial structure shown in simplified form below after copy-deletion has applied (with strikethrough indicating constituents which receive a null spellout):

As should be obvious, such an analysis relies crucially on the assumption that moved constituents leave behind full copies of themselves. It also assumes the possibility of split spellout/discontinuous spellout, in the sense that (in sentences like (15) and (16) above) a PP or CP which is the complement of a particular type of moved constituent can be spelled out in one position (in the position where it originated), and the remainder of the constituent spelled out in another (in the position where it ends up). More generally, it suggests that (in certain structures) there is a choice regarding which part of a movement chain gets deleted (an idea developed in Bobaljik 1995; Brody 1995; Groat and O’Neil 1996; Pesetsky 1997, 1998; Richards 1997; Roberts 1997; Runner 1998; Nunes 1999; Cormack and Smith 1999; and Boˇskovi´c 2001). A further possibility which this opens up is that wh-in-situ structures may involve a moved wh-expression being spelled out in its initial position (at the foot of the movement chain) rather than in its final position (at the head of the movement chain): see Pesetsky (2000) and Reintges, LeSourd and Chung (2002) for analyses of this ilk, and Watanabe (2001) for a more general discussion of wh-in-situ structures.

A further piece of evidence in support of the copy account of wh-movement comes from the fact that an overt copy of a moved pronoun may sometimes appear at its extraction site – as (19) below illustrates (the % sign indicating that only a certain percentage of speakers accept such sentences):

The sentences in (19) contain two bracketed relative clauses, one modifying someone and the other modifying anyone. The word who here is a relative pronoun which is initially merged as the complement of the verb likes, but undergoes wh-movement and is thereby moved out of the relative clause containing likes to the front of the relative clause containing know. What we’d expect to happen is that the copy of who left behind at the extraction site receives a null spellout: but this leads to ungrammaticality in (19a), for the following reason. To use a colorful metaphor developed by Ross (1967), relative clauses are islands, in the sense that they are structures which are impervious to certain types of grammatical operation. Let’s suppose that islands have the property that a copy of a moved constituent cannot be given a null spellout if the copy is inside an island and its antecedent lies outside the island: this condition prevents the italicized copy of who from receiving a null spellout in (19a), because it is contained within a relative clause island (namely the that-clause) and its bold-printed moved counterpart who lies outside the island. Some speakers resolve this problem by spelling out the copy overtly as him. Still, this raises the question of why they should spell out a copy of who as him rather than as who. Pesetsky (1997, 1998) argues that this is because of a principle which requires copies of moved constituents to be as close to unpronounceable as possible. Where islandhood constraints prevent a completely null spellout, the minimal overt spellout is simply to spell out the person/number/gender/case properties of the expression – hence the use of the third-person-masculine-singular accusative pronoun him in (19b).

Further evidence that wh-movement leaves behind a copy which is subsequently deleted comes from speech errors involving wh-copying, e.g. in relative clauses such as that bracketed below:

What’s the nature of the speech error made by the tongue-tied (or brain-drained) BBC reporter in (20)? The answer is that when moving the relative pronoun which from its initial italicized position to its subsequent bold-printed position, our intrepid reporter successfully merges a copy of which in the bold-printed position, but fails to delete the original occurrence of which in the italicized position. Such speech errors provide us with further evidence that wh-movement is a composite operation involving both copying and deletion.

A different kind of argument in support of positing that a moved wh-expression leaves behind a null copy comes from the semantics of wh-questions. Chomsky (1981, p. 324) argues that a wh-question like (21a) below has a semantic representation (more precisely, a Logical Form/LF representation) which can be shown informally as in (21b) below, with (21b) being paraphraseable as ‘Of which x (such that x is a person) is it true that she was dating x?’:

In the LF representation (21b), the quantifier which functions as an interrogative operator which serves to bind the variable x. Since a grammar must compute a semantic representation for each syntactic structure which it generates/ forms, important questions arise about how syntactic representations are to be mapped/converted into semantic representations. One such question is how a syntactic structure like (21a) can be mapped into an LF representation like (21b) containing an operator binding a variable. If a moved wh-expression leaves behind a copy, (21a) will have the syntactic structure (4) above which is repeated in simplified form (omitting all details not immediately relevant to the discussion at hand) in (22) below (where who is a null trace copy of the preposed wh-word who):

The LF-representation for (21a) can be derived from the syntactic representation (22) in a straightforward fashion if the copy who in (22) is given an LF interpretation as a variable bound by the quantifier which.

The assumption that a wh-copy (i.e. a copy of a moved wh-expression) has the semantic function of a variable which is bound by a wh-quantifier has interesting implications for the syntax of wh-movement. We noted that there is a c-command condition on binding to the effect that one constituent X can only bind another constituent Y if X c-commands Y. If we look at the structure produced by wh-movement, we find that it always results in a structure in which the moved wh-expression c-commands (by virtue of occurring higher up in the structure than) its copy. For example, in our earlier structure (4) above, the moved wh-pronoun who c-commands its copy who by virtue of the fact that who is contained within (and hence a constituent of) the C-bar was she was dating who which is the sister of the PRN-node containing the moved wh-pronoun who. It would therefore seem that a core syntactic property of wh-movement (namely the fact that it always moves a wh-expression into a higher position within the structure containing it) follows from a semantic requirement – namely the requirement that a wh-copy (by virtue of its semantic function as a variable) must be bound by a c-commanding wh-expression (which has the semantic function of an operator expression). Given their semantic function as operators, wh-words are sometimes referred to as wh-operators; likewise, wh-expressions are sometimes referred to as operator expressions, and wh-movement as operator movement.

A related semantic argument in support of the copy theory of movement is formulated by Chomsky (1995) in relation to the interpretation of sentences such as:

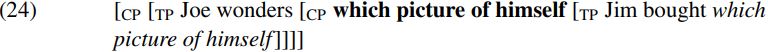

In (23), the reflexive anaphor himself can refer either to Joe or to Jim. An obvious problem posed by the latter interpretation is that a reflexive has to be c-commanded by a local antecedent (one contained within the same TP, and yet Jim does not c-command himself in (23). How can we account for the dual interpretation of himself ? Chomsky argues that the copy theory of movement provides a principled answer to this question. The QP which picture of himself is initially merged as the complement of the verb bought but is subsequently moved to the front of the bought clause, leaving behind a copy in its original position, so deriving the structure shown in skeletal form in (24) below:

Although the italicized copy of the QP which picture of himself gets deleted in the PF component, Chomsky argues that copies of moved constituents remain visible in the semantic component, and that binding conditions apply to LF representations. If (24) is the LF representation of (23), the possibility of himself referring to Jim can be attributed to the fact that the italicized occurrence of himself is c-commanded by (and contained within the same TP as) Jim at LF. On the other hand, the possibility of himself referring to Joe can be attributed to the fact that the bold-printed occurrence of himself is c-commanded by (and occurs within the same TP as) Joe.

We have seen that there is a range of empirical evidence which supports the claim that a constituent which undergoes wh-movement leaves behind a copy at its extraction site. This copy is normally given a null spellout in the PF component, though we have seen that copies may sometimes have an overt spellout, or indeed part of a moved phrase may be spelled out in one position, and part in another. We have also seen that copies of moved wh-constituents are visible in the semantic component, and play an important role in relation to the interpretation of anaphors.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)