Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Direct and Indirect speech

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Infinitival to

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

49-2

2-8-2022

2094

Infinitival to

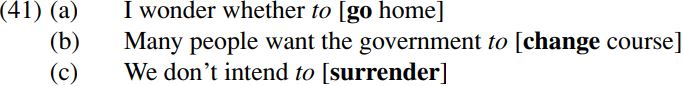

A fourth type of functor found in English is the infinitive particle to – so called because the only kind of complement it allows is one containing a verb in the infinitive form (the infinitive form of the verb is its uninflected base form, i.e. the citation form found in dictionary entries). Typical uses of infinitival to are illustrated in (41) below:

In each example in (41), the [bracketed] complement of to is an expression containing a (bold-printed) verb in the infinitive form. But what is the categorial status of infinitival to?

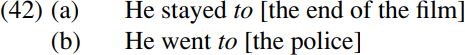

We are already familiar with an alternative use of to as a preposition, e.g. in sentences such as:

In (42), to behaves like a typical (transitive) preposition in taking a [bracketed] the-phrase (i.e. determiner phrase) as its complement (viz. the end of the film and the police). It might therefore seem that to is a preposition in both uses – one which takes a following determiner phrase complement (i.e. has a determiner expression as its complement) in (42) and a following verbal complement in (41).

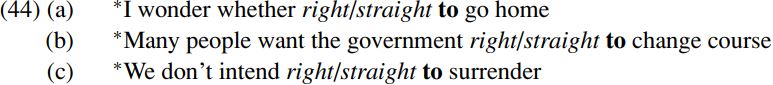

However, infinitival to is very different in its behavior from prepositional to in English: whereas prepositional to is a contentive with intrinsic lexical semantic content (e.g. it means something like ‘as far as’), infinitival to seems to be a functor with no lexical semantic content. Because of its intrinsic lexical content, the preposition to can often be modified by intensifiers like right/straight (a characteristic property of prepositions), as in:

By contrast, infinitival to (because of its lack of lexical content) cannot be intensified by right/straight:

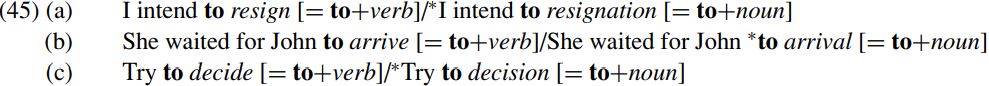

Moreover, what makes the prepositional analysis of infinitival to even more problematic is that it takes a different range of complements from prepositional to (and indeed different from the range of complements found with other prepositions). For example, prepositional to (like other prepositions) can have a noun expression as its complement, whereas infinitival to requires a verbal complement:

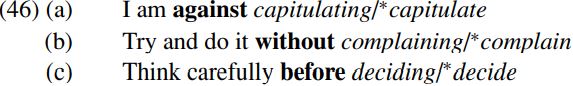

Significantly, genuine prepositions in English (such as those bold-printed in the examples below) only permit a following verbal complement when the verb is in the -ing form (known as the gerund form in this particular use), not when the verb is in the uninflected base/infinitive form:

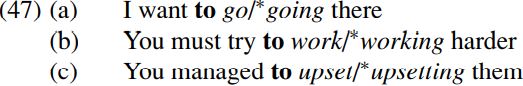

By contrast, infinitival to can only take a verbal complement when the verb is in the infinitive form, never when it is in the gerund form:

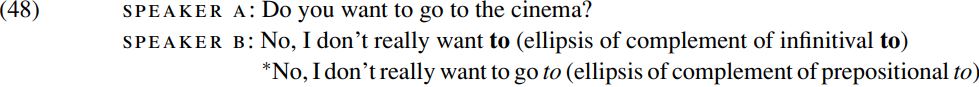

A further difference between infinitival and prepositional to (illustrated in (48) below) is that infinitival to permits ellipsis (i.e. omission) of its complement, whereas prepositional to does not:

Thus, there are compelling reasons for assuming that infinitival to is a different lexical item (i.e. a different word) belonging to a different category from prepositional to. So what category does infinitival to belong to?

Thus, there are compelling reasons for assuming that infinitival to is a different lexical item (i.e. a different word) belonging to a different category from prepositional to. So what category does infinitival to belong to?

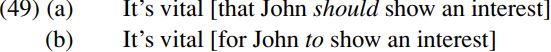

In the late 1970s, Chomsky suggested that there are significant similarities between infinitival to and a typical auxiliary like should. For example, they occupy a similar position within the clause:

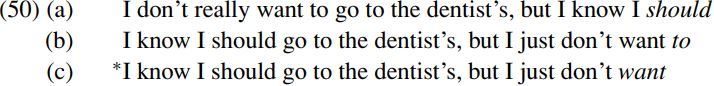

We see from (49) that to and should are both positioned between the subject John and the verb show. Moreover, just as should requires after it a verb in the infinitive form (cf. ‘You should show/∗showing/∗shown more interest in syntax’), so too does infinitival to (cf. ‘Try to show/∗showing/∗shown more interest in syntax’). Furthermore, infinitival to behaves like typical auxiliaries (e.g. should) but unlike typical non-auxiliary verbs (e.g. want) in allowing ellipsis of its complement:

The fact that to patterns like the auxiliary should in several respects strengthens the case for regarding infinitival to and auxiliaries as belonging to the same category. But what category?

Chomsky (1981, p. 18) suggested that the resulting category (comprising finite auxiliaries and infinitival to) be labelled INFL or Inflection, though (in accordance with the standard practice of using single-letter symbols to designate word categories) in later work (1986b, p. 3) he replaced INFL by the single-letter symbol I. The general idea behind this label is that finite auxiliaries are inflected forms (e.g. in ‘He doesn’t know’, the auxiliary doesn’t carries the third-person-singular present-tense inflection -s), and infinitival to serves much the same function in English as infinitive inflections in languages like Italian which have overtly inflected infinitives (so that Italian canta-re = English to sing). Under the INFL analysis, an auxiliary like should is a finite I/INFL, whereas the particle to is an infinitival I/INFL.

However, in work since the mid 1990s, a somewhat different categorization of auxiliaries and infinitival to has been adopted. As the pairs of examples in (34a–h) show, finite auxiliaries typically have two distinct forms – a present-tense form and a corresponding past-tense form (cf. pairs such as does/did, is/was, has/had, can/could etc.). Thus, a common property shared by all finite auxiliaries is that they mark (present/past) Tense. In much the same way, it might be argued that infinitival to has Tense properties, as we can see from the contrast below:

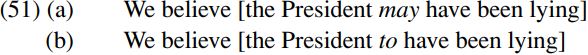

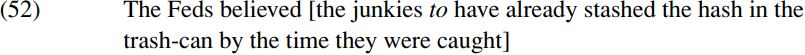

In (51a), the bracketed complement clause has a present-tense interpretation (para-phraseable as ‘We believe it is possible that the President has been lying’): this is because it contains the present-tense auxiliary may. However, the bracketed infinitive complement clause in (51b) can also have a present-tense interpretation, paraphraseable as ‘We believe the President has been lying.’ Why should this be? A plausible answer is that infinitival to carries Tense in much the same way as an auxiliary like may does. In a sentence like (51b), to is most likely to be assigned a present-tense interpretation. However, in a sentence such as (52) below:

infinitival to seems to have a past-tense interpretation, so that (52) is para-phraseable as ‘The Federal Agents believed the junkies had already stashed the hash in the trash-can by the time they were caught.’ What this suggests is that to has abstract (i.e. invisible) tense properties, and has a present-tense interpretation in structures like (51b) when the bracketed to-clause is the complement of a present-tense verb like believe, and a past-tense interpretation in structures like (52) when the bracketed to-clause is the complement of a past-tense verb like believed. If finite auxiliaries and infinitival to both have (visible or invisible) tense properties, we can assign the two of them to the same category of T/Tense marker – as is done in much contemporary work. The difference between them is sometimes said to be that auxiliaries carry finite tense (i.e. they are overtly specified for tense, in the sense that e.g. does is overtly marked as a present-tense form and did as a past-tense form) whereas infinitival to carries non-finite tense (i.e. it has an unspecified tense value which has to be determined from the context. For a more technical discussion of tense, see Julien 2001.)

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)