Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Categorizing words

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

38-2

1-8-2022

2221

Categorizing words

Given that different categories have different morphological and syntactic properties, it follows that we can use the morphological and syntactic properties of a word to determine its categorization (i.e. what category it belongs to). The morphological properties of a given word provide an initial rough guide to its categorial status: in order to determine the categorial status of an individual word, we can ask whether it has the inflectional and derivational properties of a particular category of word. For example, we can tell that happy is an adjective by virtue of the fact that it has the derivational properties of typical adjectives: it can take the negative prefix un- (giving rise to the negative adjective unhappy), the comparative/superlative suffixes -er/-est (giving rise to the forms happier/happiest), the adverbialising suffix -ly (giving rise to the adverb happily) and the nominalizing suffix -ness (giving rise to the noun happiness).

However, we cannot always rely entirely on morphological clues, owing to the fact that morphology is sometimes irregular, sometimes subject to idiosyncratic restrictions and sometimes of limited productivity. For example, although regular adverbs (like quickly, slowly, painfully etc.) generally end in the derivational suffix -ly, this is not true of irregular adverbs like fast (e.g. in He walks fast); moreover, when they have the comparative suffix -er added to them, regular adverbs lose their -ly suffix because English is a monosuffixal language (in the sense of Aronoff and Fuhrhop 2002), so that the comparative form of the adverb quickly is quicker not ∗quicklier. What all of this means is that a word belonging to a given class may have only some of the relevant morphological properties, or even (in the case of a completely irregular item) none of them.

For example, although the adjective fat has comparative/superlative forms in -er/-est (cf. fat/fatter/fattest), it has no negative un- counterpart (cf. ∗unfat) and no adverb counterpart in -ly (cf. ∗fatly). Even more exceptional is the adjective little, which has no negative un- derivative (cf. ∗unlittle), no adverb -ly derivative (cf. ∗littlely/ ∗littly), no noun derivative in -ness (at least in my variety of English – though littleness does appear in the Oxford English Dictionary), and no -er/-est derivatives (the forms ∗littler/ ∗littlest are likewise not grammatical in my variety).

What makes morphological evidence even more problematic is the fact that many morphemes may have more than one use. For example, -n/-d and -ing are inflections which attach to verbs to give perfect or progressive forms (traditionally referred to as participles). However, certain -n/-d and -ing forms seem to function as adjectives, suggesting that -ing and -n/-d can also serve as adjectivalising (i.e. adjective-forming) morphemes. So, although a word like interesting can function as a verb (in sentences like Her charismatic teacher was gradually interesting her in syntax), it can also function as an adjective (used attributively in structures like This is an interesting book, and predicatively in structures like This book is very interesting). In its use as an adjective, the word interesting has the negative derivative uninteresting (as in It was a rather uninteresting play) and the -ly adverb derivative interestingly (though, like many other adjectives, it has no noun derivative in -ness, and no comparative or superlative derivatives in -er/-est). Similarly, although -n/-d can serve as a perfect participle inflection (in structures like We hadn’t known/expected that he would quit), it should be noted that many words ending in -n/-d can also function as adjectives. For example, the word known in an expression such as a known criminal seems to function as an (attributive) adjective, and in this adjectival use it has a negative un- counterpart (as in expressions like the tomb of the unknown warrior). Similarly, the form expected functions as a perfect participle verb form in structures like We hadn’t expected him to complain, but seems to function as an (attributive) adjective in structures such as He gave the expected reply; in its adjectival (though not in its verbal) use, it has a negative un- derivative, and the resultant negative adjective unexpected in turn has the noun derivative unexpectedness.

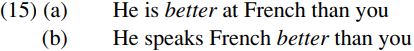

So, given the potential problems which arise with morphological criteria, it is unwise to rely solely on morphological evidence in determining categorial status: rather, we should use morphological criteria in conjunction with syntactic criteria (i.e. criteria relating to the range of positions that words can occupy within phrases and sentences). One syntactic test which can be used to determine the category that a particular word belongs to is that of substitution – i.e. seeing whether (in a given sentence) the word in question can be substituted by a regular noun, verb, preposition, adjective, or adverb etc. We can use the substitution technique to differentiate between comparative adjectives and adverbs ending in -er, since they have identical forms. For example, in the case of sentences like:

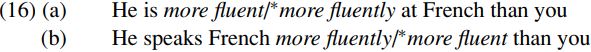

we find that better can be replaced by a more+adjective expression like more fluent in (15a) but not (15b), and conversely that better can be replaced by a more+adverb expression like more fluently in (15b) but not in (15a):

Thus, the substitution test provides us with syntactic evidence that better is an adjective in (15a), but an adverb in (15b).

The overall conclusion to be drawn from our discussion is that morphological evidence may sometimes be inconclusive, and has to be checked against syntactic evidence. A useful syntactic test which can be employed is that of substitution: for example, if a morphologically indeterminate word can be substituted by a regular noun wherever it occurs, then the relevant word has the same categorial status as the substitute word which can replace it, and so is a noun.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)