Parameter-setting

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المؤلف:

Andrew Radford

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

المصدر:

Minimalist Syntax

الجزء والصفحة:

21-1

الجزء والصفحة:

21-1

29-7-2022

29-7-2022

1819

1819

Parameter-setting

The theory of parameters outlined in the previous section has important implications for a theory of language acquisition. If all grammatical variation can be characterized in terms of a series of parameters with binary settings, it follows that the only grammatical learning which children have to undertake in relation to the syntactic properties of the relevant class of constructions is to determine (on the basis of their linguistic experience) which of the two alternative settings for each parameter is the appropriate one for the language being acquired. So, for example, children have to learn whether the native language they are acquiring is a null-subject language or not, whether it is a wh-movement language or not, and whether it is a head-first language or not . . . and so on for all the other parameters along which languages vary. Of course, children also face the formidable task of lexical learning – i.e. building up their vocabulary in the relevant language, learning what words mean and what range of forms they have (e.g. whether they are regular or irregular in respect of their morphology), what kinds of structures they can be used in and so on. On this view, the acquisition of grammar involves the twin tasks of lexical learning and parameter-setting.

This leads us to the following view of the language acquisition process. The central task which the child faces in acquiring a language is to construct a grammar of the language. The innate Language Faculty incorporates (i) a set of universal grammatical principles, and (ii) a set of grammatical parameters which impose severe constraints on the range of grammatical variation permitted in natural languages (perhaps limiting variation to binary choices). Since universal principles don’t have to be learned, the child’s syntactic learning task is limited to that of parameter-setting (i.e. determining an appropriate setting for each of the relevant grammatical parameters). For obvious reasons, the theory outlined here (developed by Chomsky at the beginning of the 1980s and articulated in Chomsky 1981) is known as Principles-and-Parameters Theory/PPT.

The PPT model clearly has important implications for the nature of the language acquisition process, since it vastly reduces the complexity of the acquisition task which children face. PPT hypothesises that grammatical properties which are universal will not have to be learned by the child, since they are wired into the language faculty and hence part of the child’s genetic endowment: on the contrary, all the child has to learn are those grammatical properties which are subject to parametric variation across languages. Moreover, the child’s learning task will be further simplified if it turns out (as research since 1980 has suggested) that the values which a parameter can have fall within a narrowly specified range, perhaps characterisable in terms of a series of binary choices. This simplified parameter-setting model of the acquisition of grammar has given rise to a metaphorical acquisition model in which the child is visualized as having to set a series of switches in one of two positions (up/down) – each such switch representing a different parameter. In the case of the Head-Position Parameter, we can imagine that if the switch is set in the up position (for particular types of head), the language will show head-first word order in relevant kinds of structure, whereas if it is set in the down position, the order will be head-last. Of course, an obvious implication of the switch metaphor is that the switch must be set in either one position or the other, and cannot be set in both positions. (This would preclude, for example, the possibility of a language having both head-first and head-last word order in a given type of structure.)

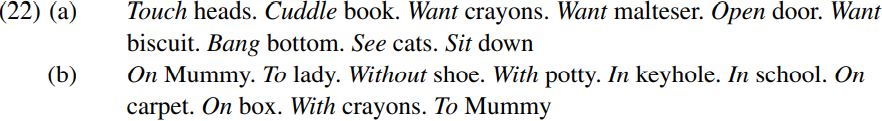

The assumption that acquiring the grammar of a language involves the relatively simple task of setting a number of grammatical parameters provides a natural way of accounting for the fact that the acquisition of specific parameters appears to be a remarkably rapid and error-free process in young children. For example, young children acquiring English as their native language seem to set the Head-Position Parameter at its appropriate head-first setting from the very earliest multiword utterances they produce (at around eighteen months of age), and seem to know (tacitly, not explicitly, of course) that English is a head-first language. Accordingly, the earliest verb phrases and prepositional phrases produced by young children acquiring English consistently show verbs and prepositions positioned before their complements, as structures such as the following indicate (produced by a young boy called Jem/James at age twenty months; head verbs are italicized in (22a) and head prepositions in (22b), and their complements are in non-italic print):

The obvious conclusion to be drawn from structures like (22) is that children like Jem consistently position heads before their complements from the very earliest multiword utterances they produce. They do not use different orders for different words of the same type (e.g. they don’t position the verb see after its complement but the verb want before its complement), or for different types of words (e.g. they don’t position verbs before and prepositions after their complements).

The obvious conclusion to be drawn from structures like (22) is that children like Jem consistently position heads before their complements from the very earliest multiword utterances they produce. They do not use different orders for different words of the same type (e.g. they don’t position the verb see after its complement but the verb want before its complement), or for different types of words (e.g. they don’t position verbs before and prepositions after their complements).

A natural question to ask at this point is how we can provide a principled explanation for the fact that from the very onset of multiword speech we find English children correctly positioning heads before their complements. The Principles-and-Parameters model enables us to provide an explanation for why children manage to learn the relative ordering of heads and complements in such a rapid and error-free fashion. The answer provided by the model is that learning this aspect of word order involves the comparatively simple task of setting a binary parameter at its appropriate value. This task will be a relatively straightforward one if the language faculty tells the child that the only possible choice is for a given type of structure in a given language to be uniformly head-first or uniformly head-last. Given such an assumption, the child could set the parameter correctly on the basis of minimal linguistic experience. For example, once the child is able to parse (i.e. grammatically analyze) an adult utterance such as Help Daddy and knows that it contains a verb phrase comprising the head verb help and its complement Daddy, then (on the assumption that the language faculty specifies that all heads of a given type behave uniformly with regard to whether they are positioned before or after their complements), the child will automatically know that all verbs in English are canonically (i.e. normally) positioned before their complements.

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة