The Language Faculty

Mention of learnability leads us to consider the related goal of developing a theory of language acquisition. An acquisition theory is concerned with the question of how children acquire grammars of their native languages. Children generally produce their first recognizable word (e.g. Mama or Dada) by the age of twelve months. For the next six months or so, there is little apparent evidence of grammatical development in their speech production, although the child’s productive vocabulary typically increases by about five words a month until it reaches around thirty words at age eighteen months. Throughout this single-word stage, children’s utterances comprise single words spoken in isolation: e.g. a child may say Apple when reaching for an apple, or Up when wanting to climb up onto her mother’s knee. During the single-word stage, it is difficult to find any clear evidence of the acquisition of grammar, in that children do not make productive use of inflections (e.g. they don’t add the plural -s ending to nouns, or the past-tense -d ending to verbs), and don’t productively combine words together to form two-and three-word utterances

At around the age of eighteen months (though with considerable variation from one child to another), we find the first visible signs of the acquisition of grammar: children start to make productive use of inflections (e.g. using plural nouns like doggies alongside the singular form doggy, and inflected verb forms like going/gone alongside the uninflected verb form go), and similarly start to produce elementary two- and three-word utterances such as Want Teddy, Eating cookie, Daddy gone office etc. From this point on, there is a rapid expansion in their grammatical development, until by the age of around thirty months they have typically acquired most of the inflections and core grammatical constructions used in English, and are able to produce adult-like sentences such as Where’s Mummy gone? What’s Daddy doing? Can we go to the zoo, Daddy? etc. (though occasional morphological and syntactic errors persist until the age of four years or so – e.g. We goed there with Daddy, What we can do? etc.).

So, the central phenomenon which any theory of language acquisition must seek to explain is this: how is it that after a long drawn-out period of many months in which there is no obvious sign of grammatical development, at around the age of eighteen months there is a sudden spurt as multiword speech starts to emerge, and a phenomenal growth in grammatical development then takes place over the next twelve months? This uniformity and (once the spurt has started) rapidity in the pattern of children’s linguistic development are the central facts which a theory of language acquisition must seek to explain. But how?

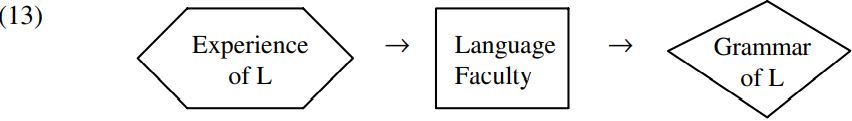

Chomsky maintains that the most plausible explanation for the uniformity and rapidity of first language acquisition is to posit that the course of acquisition is determined by a biologically endowed innate Language Faculty (or language acquisition program, to borrow a computer software metaphor) within the brain, which provides children with a genetically transmitted algorithm (i.e. set of procedures) for developing a grammar, on the basis of their linguistic experience (i.e. on the basis of the speech input they receive). The way in which Chomsky visualizes the acquisition process can be represented schematically as in (13) below (where L is the language being acquired):

Children acquiring a language will observe people around them using the language, and the set of expressions in the language which a child hears (and the contexts in which they are used) in the course of acquiring the language constitute the child’s linguistic experience of the language. This experience serves as input to the child’s language faculty, which provides the child with a procedure for (subconsciously) analyzing the experience and devising a grammar of the language being acquired. Thus, the input to the language faculty is the child’s experience, and the output of the language faculty is a grammar of the language being acquired.

The hypothesis that the course of language acquisition is determined by an innate language faculty is known popularly as the innateness hypothesis. Chomsky maintains that the ability to speak and acquire languages is unique to human beings, and that natural languages incorporate principles which are also unique to humans and which reflect the nature of the human mind:

Whatever evidence we do have seems to me to support the view that the ability to acquire and use language is a species-specific human capacity, that there are very deep and restrictive principles that determine the nature of human language and are rooted in the specific character of the human mind. (Chomsky 1972, p. 102)

Moreover, he notes, language acquisition is an ability which all humans possess, entirely independently of their general intelligence

Even at low levels of intelligence, at pathological levels, we find a command of language that is totally unattainable by an ape that may, in other respects, surpass a human imbecile in problem-solving activity and other adaptive behavior. (Chomsky 1972, p. 10)

In addition, the apparent uniformity in the types of grammars developed by different speakers of the same language suggests that children have genetic guidance in the task of constructing a grammar of their native language:

We know that the grammars that are in fact constructed vary only slightly among speakers of the same language, despite wide variations not only in intelligence but also in the conditions under which language is acquired. (Chomsky 1972, p. 79)

Furthermore, the rapidity of acquisition (once the grammar spurt has started) also points to genetic guidance in grammar construction:

Otherwise it is impossible to explain how children come to construct grammars... under the given conditions of time and access to data. (Chomsky 1972, p. 113)

(The sequence ‘under... data’ means simply ‘in so short a time, and on the basis of such limited linguistic experience.’) What makes the uniformity and rapidity of acquisition even more remarkable is the fact that the child’s linguistic experience is often (i.e. imperfect), since it is based on the linguistic performance of adult speakers, and this may be a poor reflection of their competence:

A good deal of normal speech consists of false starts, disconnected phrases, and other deviations from idealized competence. (Chomsky 1972, p. 158)

If much of the speech input which children receive is degenerate (because of performance errors), how is it that they can use this degenerate experience to develop a (competence) grammar which specifies how to form grammatical sentences? Chomsky’s answer is to draw the following analogy:

Descartes asks: how is it when we see a sort of irregular figure drawn in front of us we see it as a triangle? He observes, quite correctly, that there’s a disparity between the data presented to us and the percept that we construct. And he argues, I think quite plausibly, that we see the figure as a triangle because there’s something about the nature of our minds which makes the image of a triangle easily constructible by the mind. (Chomsky 1968, p. 687)

The obvious implication is that in much the same way as we are genetically predisposed to analyze shapes (however irregular) as having specific geometrical properties, so too we are genetically predisposed to analyze sentences (however ungrammatical) as having specific grammatical properties. (For evaluation of this kind of degenerate input argument, see Pullum and Scholz 2002; Thomas 2002; Sampson 2002; Fodor and Crowther 2002; Lasnik and Uriagereka 2002; Legate and Yang 2002; Crain and Pietroski 2002; and Scholz and Pullum 2002.)

A further argument Chomsky uses in support of the innateness hypothesis relates to the fact that language acquisition is an entirely subconscious and involuntary activity (in the sense that you can’t consciously choose whether or not to acquire your native language – though you can choose whether or not you wish to learn chess); it is also an activity which is largely unguided (in the sense that parents don’t teach children to talk):

Children acquire . . . languages quite successfully even though no special care is taken to teach them and no special attention is given to their progress. (Chomsky 1965, pp. 200–1)

The implication is that we don’t learn to have a native language, any more than we learn to have arms or legs; the ability to acquire a native language is part of our genetic endowment – just like the ability to learn to walk.

Studies of language acquisition lend empirical support for the innateness hypothesis. Research has suggested that there is a critical period for the acquisition of syntax, in the sense that children who learn a given language before puberty generally achieve native competence in it, whereas those who acquire a (first or second) language after the age of nine or ten years rarely manage to achieve native-like syntactic competence: see Lenneberg (1967), Hurford (1991) and Smith (1998, 1999) for discussion. A particularly poignant example of this is a child called Genie (see Curtiss 1977; Rymer 1993), who was deprived of speech input and kept locked up on her own in a room until age thirteen. When eventually taken into care and exposed to intensive language input, her vocabulary grew enormously, but her syntax never developed. This suggests that the acquisition of syntax is determined by an innate ‘language acquisition programme’ which is in effect switched off at the onset of puberty. (For further discussion of the innateness hypothesis, see Antony and Hornstein 2002.)

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

الاكثر قراءة في Syntax

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة