Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Metacognitive awareness

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

242-8

27-5-2022

1287

Metacognitive awareness

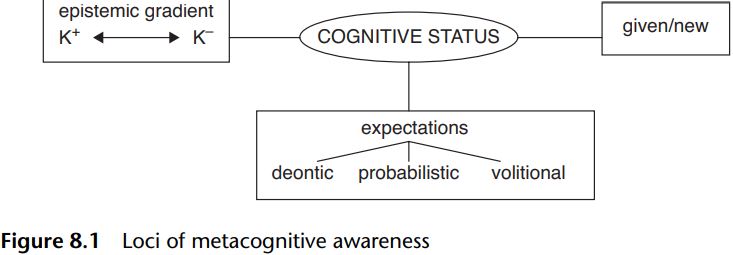

Metacognitive awareness refers to the reflexive presentations of the cognitive status of information and understandings of context and common ground amongst participants. It includes reflexive awareness about who knows what and how certain they are about it (i.e. its epistemic status), and what counts as new or given information for participants (i.e. its given/new status), as well as the expectations of participants about what can, may or should happen (i.e. its deontic status). In other words, it involves reflexive presentations amongst participants of cognitive-emotive states or processes, such as what is assumed to be known (or not known), their respective attitudes, expectations and so on.

This may involve speakers directing the attention of recipients to particular elements in the context, for instance. We have already discussed one of the key ways in which this occurs, namely, through referring expressions. We introduced the Accessibility Marking Scale and the Givenness Hierarchy. These both involve the speaker making assumptions about how accessible the referent is for the recipient. More generally, the use of referring expressions involves a consideration of the assumed cognitive status of the referents in question for the recipient. The cognitive status of a referent can range from being in focus, through being in memory but not currently active, to being completely unknown. The metapragmatic exchange between Brett and Jermaine that we discussed is, in part, an example of metacognitive awareness surfacing in interaction. The confusion arises in this instance because while the referent should have been in focus for both of them (at least from the perspective of the viewing audience), they treat the referent as unknown to the other. In other words, the interaction is driven by both parties assuming the other participant does not know this contextual information.

Reflexive presentations of information may also involve attempts by speakers to direct the attention of the recipient to some particular information. We briefly discussed this, when we introduced discourse markers, particles and formulae that speakers use to direct the attention of recipients to particular information, or more generally, to indicate how recipients should take or process upcoming information. We also briefly touched upon this issue, when we discussed the particle yet, which is analyzed by (neo-)Griceans as giving rise to a conventional implicature. For the sake of simplicity, we did not point out that Relevance theorists offer a somewhat different account of such phenomena, namely, their claim that there is another kind of meaning that contrasts with the conceptual or representational type of pragmatic meaning, which was the primary focus. This second type of meaning is termed procedural meaning (Blakemore 1987, 2002; Wilson and Sperber 1993), and is assumed to encode “constraints on the inferential phase of comprehension” (Wilson and Sperber 1993: 102) rather than having any conceptual content. Conventional implicatures, for example, have thus been re-analyzed by Relevance theorists as forms of procedural meaning, in part because it is well-known that the meanings of words such as but, even, and yet are notoriously difficult to be brought to consciousness. Relevance theorists argue that this difficulty indicates we are dealing with a fundamentally different kind of meaning. Here, we suggest that a metapragmatic account allows us to acknowledge that while certain linguistic units do not necessarily have any conceptual “content” that can be readily pinned down, they nevertheless do indicate a particular cognitive state or stance on the part of the speaker vis-à-vis the recipient.

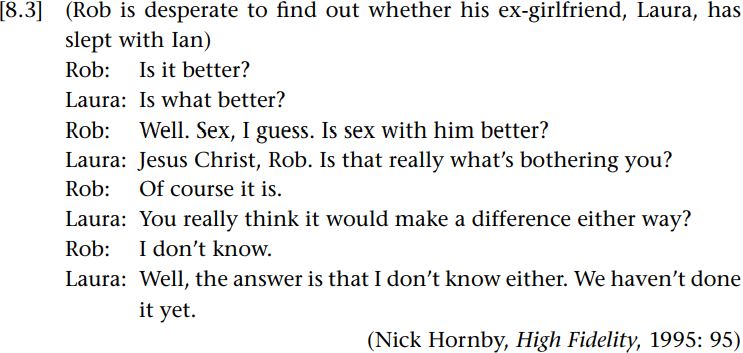

Let us reconsider the example of the use of yet from the novel High Fidelity:

The question for Rob is what is meant by yet here? It belongs to the general class of discourse markers used to indicate contrast. But this begs the question of just what is being contrasted here. From a metacognitive perspective, Laura is reflexively presenting her expectations vis-à-vis Rob. In other words, Laura indicates that what she expects might happen in her relationship with Ian (i.e. a possibility), contrasts with what Rob might expect should, or to be precise, should not happen (i.e. an obligation). The upshot is what we have here, a contrast in their respective expectations in regard to her relationship with Ian (and by implication, with Rob). This contrast involves a reflexive display of the cognitive status of particular expectations on the part of those participants.

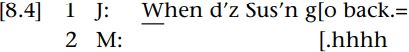

Another well-known instance of a pragmatic marker that can be analyzed as reflexively displaying awareness of the cognitive status of information for participants is the use of oh. Heritage (1984a) was the first to demonstrate that when oh is produced in response to information, it indicates (on the surface at least) a change of knowledge state on the part of a participant. In other words, it is used to register this information as new in some way for that user. Take the excerpt below, which is taken from a recording of a conversation between two friends:

After hearing the information offered by Mel that Jack sought (i.e. when Susan is going back), he responds with oh in line 5. Heritage argues that when oh occurs in this position, and is followed by a shift to a new action (in this particular example, an assertion of other information by Mel about Steven), the user reflexively displays the assumption that the information is somehow new to him or her. In other words, the use of oh in this way involves issues of epistemics, that is, how certain a participant is about information, and whether it is taken to be given or new. It thus indexes reflexive awareness of the cognitive status of information for the participants in a manner analogous to the example of yet, which we considered above. It is important to note, however, that the particular cognitive state that such pragmatic markers reflexively index depends on their sequential environment. Oh may also be used to register or mark a change of state in orientation or awareness, such as when noticing something, as well as to foreshadow possible forthcoming trouble in responding to a question (see Heritage 1998).

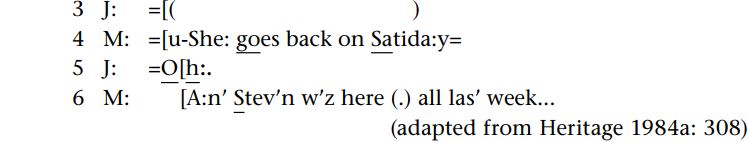

Actually is yet another example of a pragmatic marker where the metapragmatic function of the particle depends on its sequential environment. In early work it was characterized as marking an assumption as “true at one particular point in the past time (which the speaker does not further specify) but not necessarily at any other point in time” (Watts 1988: 254). In subsequent research, the work that actually does was broadened to include the negotiation of (often implicit) claims that contradict the recipient’s expectations (Smith and Jucker 2000). These expectations relate specifically to either (1) a user’s commitment to a particular claim, (2) an affective evaluation of a fact or set of facts, or (3) a judgement about the newsworthiness of information. Consider the following excerpt from a conversation between two undergraduate students:

Here, Betty marks the information in her response as unexpected in that she is making a stronger claim (i.e. she really likes it) than the candidate answer offered in the initial question (i.e. she likes it). Through the formulation of her question, then, Ann indicates, in the form of an implicated premise, that Betty wouldn’t be expected to “really like” psychology. It is towards this expectation that Betty orients through her use of actually.

Pragmatic markers are very complex. As we have seen, they are not restricted to reflexive presentations or displays of the cognitive status of information or understandings of context/common ground amongst participants (i.e. markers of metacognitive awareness). They may also involve other kinds of reflexivity, both metarepresentational and metacognitive awareness (which we will discuss in further detail), and so they can evidently indicate various different types of metapragmatic awareness. It is for this reason that pragmatic markers are so difficult to define categorically. It is also for this reason that we propose that they are analyzed more productively from the perspective of different types of reflexive awareness. In the case of metacognitive awareness, we are dealing with the reflexive presentation of the cognitive status of information.

This cognitive status can encompass a number of different dimensions, as summarized in Figure 8.1. There are arguably three key loci for the cognitive status of information. The first is the so-called epistemic gradient between participants (Heritage 2012; Heritage and Raymond 2012). This involves the degree to which participants are aware (or, more accurately, display awareness of) who knows what, and to what degree of certainty. This degree of certainty lies on a gradient from “definitively knowing” (K+) through to “not knowing” (K– ). A second related dimension is that between given and new information. The former is treated as lying within the common ground of participants, while the latter is treated as lying outside of it. Third, we can also talk of reflexive awareness in relation to expectations. The expectations be may be deontic (i.e. what participants think should or ought to be the case), probabilistic (i.e. what participants think is likely to be the case), or volitional (i.e. what participants want to be the case) in nature.

Pragmatic markers can be used to index reflexive awareness of all these different forms of cognitive status amongst participants, as we have discussed. Most importantly, the same linguistic form, as we have seen, can be used to present different cognitive states depending on its sequential environment. Accounts that treat pragmatic markers as either encoding constraints on the inferential phase of comprehension (i.e. as forms of procedural meaning), or as conventionally implicating non-truth-conditional meaning (i.e. as instances of conventional implicature), are arguably not able to do sufficient justice to such interactional nuances, although, to be fair, such accounts were not originally designed to do so.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)