Grammar

Tenses

Present

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous

Past

Past Simple

Past Continuous

Past Perfect

Past Perfect Continuous

Future

Future Simple

Future Continuous

Future Perfect

Future Perfect Continuous

Parts Of Speech

Nouns

Countable and uncountable nouns

Verbal nouns

Singular and Plural nouns

Proper nouns

Nouns gender

Nouns definition

Concrete nouns

Abstract nouns

Common nouns

Collective nouns

Definition Of Nouns

Animate and Inanimate nouns

Nouns

Verbs

Stative and dynamic verbs

Finite and nonfinite verbs

To be verbs

Transitive and intransitive verbs

Auxiliary verbs

Modal verbs

Regular and irregular verbs

Action verbs

Verbs

Adverbs

Relative adverbs

Interrogative adverbs

Adverbs of time

Adverbs of place

Adverbs of reason

Adverbs of quantity

Adverbs of manner

Adverbs of frequency

Adverbs of affirmation

Adverbs

Adjectives

Quantitative adjective

Proper adjective

Possessive adjective

Numeral adjective

Interrogative adjective

Distributive adjective

Descriptive adjective

Demonstrative adjective

Pronouns

Subject pronoun

Relative pronoun

Reflexive pronoun

Reciprocal pronoun

Possessive pronoun

Personal pronoun

Interrogative pronoun

Indefinite pronoun

Emphatic pronoun

Distributive pronoun

Demonstrative pronoun

Pronouns

Pre Position

Preposition by function

Time preposition

Reason preposition

Possession preposition

Place preposition

Phrases preposition

Origin preposition

Measure preposition

Direction preposition

Contrast preposition

Agent preposition

Preposition by construction

Simple preposition

Phrase preposition

Double preposition

Compound preposition

prepositions

Conjunctions

Subordinating conjunction

Correlative conjunction

Coordinating conjunction

Conjunctive adverbs

conjunctions

Interjections

Express calling interjection

Phrases

Sentences

Grammar Rules

Passive and Active

Preference

Requests and offers

wishes

Be used to

Some and any

Could have done

Describing people

Giving advices

Possession

Comparative and superlative

Giving Reason

Making Suggestions

Apologizing

Forming questions

Since and for

Directions

Obligation

Adverbials

invitation

Articles

Imaginary condition

Zero conditional

First conditional

Second conditional

Third conditional

Reported speech

Demonstratives

Determiners

Linguistics

Phonetics

Phonology

Linguistics fields

Syntax

Morphology

Semantics

pragmatics

History

Writing

Grammar

Phonetics and Phonology

Semiotics

Reading Comprehension

Elementary

Intermediate

Advanced

Teaching Methods

Teaching Strategies

Assessment

Reflection: Cooperation and “not-jokes” in American English

المؤلف:

Jonathan Culpeper and Michael Haugh

المصدر:

Pragmatics and the English Language

الجزء والصفحة:

95-4

6-5-2022

900

Reflection: Cooperation and “not-jokes” in American English

We noted earlier that what counts as cooperation in applying the Cooperative Principle depends on the type of activity or talk the participants are engaging in. To engage in joke telling, for instance, requires the contextualization of conversation maxims relative to the genre of joke telling. This genre involves a set of normative expectations that flesh out the Cooperative Principle and maxims in the form of a particular activity type. Take the much maligned subcategory of “not-jokes”, for instance, which originated amongst speakers of American English. This involves the speaker first violating the quality maxim by asserting something which he or she is seemingly committed to, and then explicitly signaling he or she has violated it by uttering “not”. In this way, the speaker makes explicit that he or she is being sarcastic and also implicates that the hearer (or possibly a third party) is someone who is gullible or easily misled.

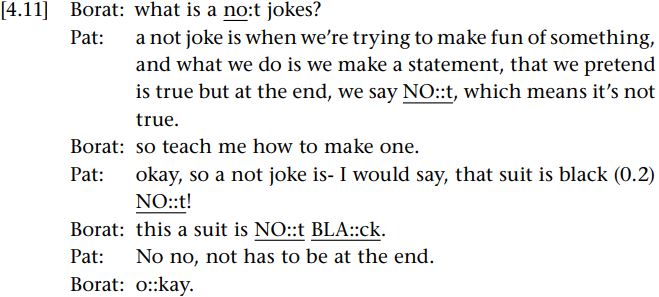

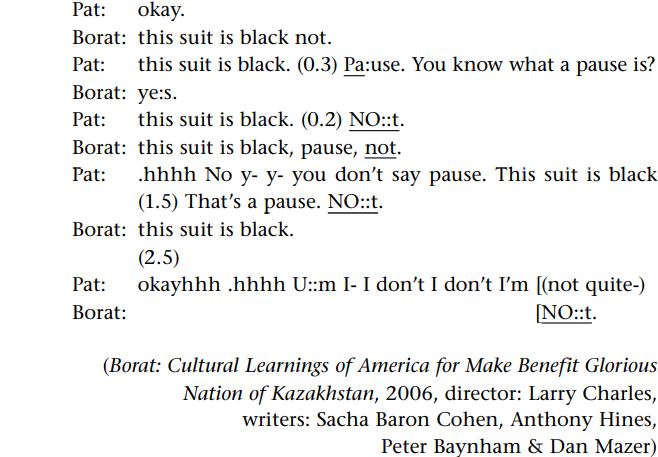

There are particular expectations, however, about the timing and intonation with which not is delivered for an utterance to count as a not-joke. Consider the following exchange between Borat (a satirical character allegedly from Kazakhstan) and a humour coach in the US.

In order to make the assertion This suit is black to subsequently count as initiating a not-joke rather than being simply a lie or mistaken observation on the part of the speaker, the speaker needs to indicate or signal that the “accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange” here is to engage in a specific kind of joke telling. This is achieved through delivering the subsequent not with a particular intonation (i.e. with a markedly louder volume and elongation of the vowel sound) and after a “beat” of the conversation has passed (i.e. a pause of approximately 0.2 of a second). In the context of a not-joke, this is what it means to “make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs”.

When a speaker flouts a conversational maxim, as in the above examples, it is done in a way that makes the non-observance of the maxim recognizable to others in normal circumstances by blatantly failing to fulfil it (Grice [1975]1989: 49). However, Grice proposed that conversational implicatures can be made available through other ways of not observing the conversational maxims. A number of different frameworks for categorizing different types of non-observance of maxims have been proposed (see, for example, Greenall 2009; Mooney 2004; Thomas 1995), but we will concentrate here on just two of the most important types, namely, violating and infringing the conversational maxims.

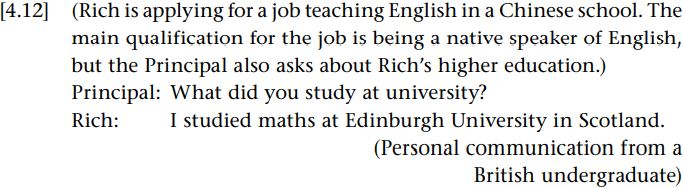

Violating a maxim involves deliberate non-observance by the speaker of a maxim in a way that would not be recognizable to others in normal circumstances. In the following example, Rich implicates through his response that he graduated with a degree in maths from Edinburgh University.

This follows from the Quantity2 maxim (“do not make your contribution more informative than is required”) through standard inferences that follow from what is simply described here by Rich in order to maintain the supposition that he is observing the Cooperative Principle. However, Rich does not mention that he left Edinburgh after his first year of study, and so this constitutes a (deliberate) violation of the Quality1 maxim. Violations of maxims thus always involve the speaker intending to mislead others or even lying (Mooney 2004: 914). This intention is a covert one, however, and so differs from the Gricean or communicative intention that we discussed.

Differentiating between these different types of non-observance can be difficult in practice, however, since they rely in part on recognizing the intentions of the speaker, which are not necessarily always clear to others (or even to the speakers themselves). Distinguishing between flouting, violating and infringing maxims thus leads us beyond Grice’s primary focus on what the speaker intended to a consideration of the recognition or reconstruction of the speaker’s intentions by the hearer.

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

الاكثر قراءة في pragmatics

اخر الاخبار

اخر الاخبار

اخبار العتبة العباسية المقدسة

الآخبار الصحية

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة

قسم الشؤون الفكرية يصدر كتاباً يوثق تاريخ السدانة في العتبة العباسية المقدسة "المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة

"المهمة".. إصدار قصصي يوثّق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة فتوى الدفاع المقدسة للقصة القصيرة (نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)

(نوافذ).. إصدار أدبي يوثق القصص الفائزة في مسابقة الإمام العسكري (عليه السلام)